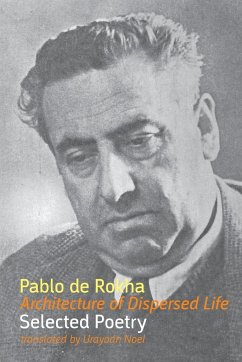

Architecture of Dispersed Life

Selected Poetry

Versandkostenfrei!

Versandfertig in 1-2 Wochen

21,99 €

inkl. MwSt.

PAYBACK Punkte

11 °P sammeln!

"More tragic and irremediable than his enemy Pablo Neruda’s, more vast than Ezra Pound’s, more profound than Rilke’s, the great poetry of Pablo de Rokha reveals to us the desperate landscapes of hope. De Rokha committed suicide on December 10, 1968. He was perhaps the major poet of the 20th century." —Raúl Zurita "This book is an event, a monumental work of translation and poetry that will force us to rethink our understanding of global modernism and the hemispheric avant-garde. Pablo de Rokha, finally accessible to the English-speaking world, is a major Chilean poet of the early 20th...

"More tragic and irremediable than his enemy Pablo Neruda’s, more vast than Ezra Pound’s, more profound than Rilke’s, the great poetry of Pablo de Rokha reveals to us the desperate landscapes of hope. De Rokha committed suicide on December 10, 1968. He was perhaps the major poet of the 20th century." —Raúl Zurita "This book is an event, a monumental work of translation and poetry that will force us to rethink our understanding of global modernism and the hemispheric avant-garde. Pablo de Rokha, finally accessible to the English-speaking world, is a major Chilean poet of the early 20th century, who ought to sit front and center alongside Neruda, Mistral, Huidobro, Vallejo and Girondo; and Urayoán Noel’s work here as translator and editor is a historical and archival restoration on a massive scale. Noel’s evocative introduction—which refuses "to disentangle de Rokha the vanguardist from de Rokha the indigenous poet"—brilliantly situates de Rokha as a poet who is as focused on the local as he is on the international. De Rokha strikes the modern reader as entirely contemporary, in his form, language and, most interestingly, in how he foretells the political and economic violence of a global, neoliberal continuum. This translation will dazzle, and de Rokha’s voice, with its hyperbole, its contradictions, its obsessive critique of Yankeeland, will, inevitably, say as much about 2018 as it does about 1922." —Daniel Borzutzky