17,99 €

inkl. MwSt.

Versandfertig in über 4 Wochen

9 °P sammeln

- Broschiertes Buch

- Merkliste

- Auf die Merkliste

- Bewerten Bewerten

- Teilen

- Produkt teilen

- Produkterinnerung

- Produkterinnerung

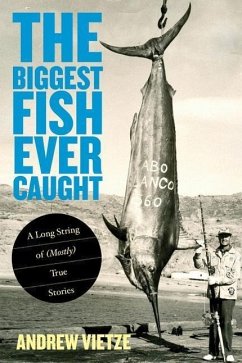

Tells the tales behind the International Game Fishing Association's record-holding fish, including where they were bagged, what lines/lures the anglers used, and other tips and tricks.

Andere Kunden interessierten sich auch für

![Stalking Trophy Brown Trout: A Fly-Fisher's Guide to Catching the Biggest Trout of Your Life Stalking Trophy Brown Trout: A Fly-Fisher's Guide to Catching the Biggest Trout of Your Life]() John HoltStalking Trophy Brown Trout: A Fly-Fisher's Guide to Catching the Biggest Trout of Your Life22,99 €

John HoltStalking Trophy Brown Trout: A Fly-Fisher's Guide to Catching the Biggest Trout of Your Life22,99 €![Fly Fishing the Inland Oceans: An Angler's Guide to Finding and Catching Fish in the Great Lakes Fly Fishing the Inland Oceans: An Angler's Guide to Finding and Catching Fish in the Great Lakes]() Jerry DarkesFly Fishing the Inland Oceans: An Angler's Guide to Finding and Catching Fish in the Great Lakes26,99 €

Jerry DarkesFly Fishing the Inland Oceans: An Angler's Guide to Finding and Catching Fish in the Great Lakes26,99 €![Martha's Vineyard Fish Tales: How to Catch Fish, Rake Clams, and Jig Squid, with Entertaining Tales about the Sometimes Crazy Pursuit of Fish Martha's Vineyard Fish Tales: How to Catch Fish, Rake Clams, and Jig Squid, with Entertaining Tales about the Sometimes Crazy Pursuit of Fish]() Nelson SigelmanMartha's Vineyard Fish Tales: How to Catch Fish, Rake Clams, and Jig Squid, with Entertaining Tales about the Sometimes Crazy Pursuit of Fish22,99 €

Nelson SigelmanMartha's Vineyard Fish Tales: How to Catch Fish, Rake Clams, and Jig Squid, with Entertaining Tales about the Sometimes Crazy Pursuit of Fish22,99 €![A Fish Caught in Time A Fish Caught in Time]() Samantha WeinbergA Fish Caught in Time19,99 €

Samantha WeinbergA Fish Caught in Time19,99 €![Fish On, Fish Off Fish On, Fish Off]() Stephen SautnerFish On, Fish Off18,99 €

Stephen SautnerFish On, Fish Off18,99 €![Kayak Fly Fishing: Everything You Need to Know to Start Catching Fish Kayak Fly Fishing: Everything You Need to Know to Start Catching Fish]() Ben DuchesneyKayak Fly Fishing: Everything You Need to Know to Start Catching Fish26,99 €

Ben DuchesneyKayak Fly Fishing: Everything You Need to Know to Start Catching Fish26,99 €![Large Mammals of the Rocky Mountains: Everything You Need to Know about the Continent's Biggest Animals--From Elk to Grizzly Bears and More Large Mammals of the Rocky Mountains: Everything You Need to Know about the Continent's Biggest Animals--From Elk to Grizzly Bears and More]() Jack BallardLarge Mammals of the Rocky Mountains: Everything You Need to Know about the Continent's Biggest Animals--From Elk to Grizzly Bears and More30,99 €

Jack BallardLarge Mammals of the Rocky Mountains: Everything You Need to Know about the Continent's Biggest Animals--From Elk to Grizzly Bears and More30,99 €-

-

-

Tells the tales behind the International Game Fishing Association's record-holding fish, including where they were bagged, what lines/lures the anglers used, and other tips and tricks.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Produktdetails

- Produktdetails

- Verlag: Globe Pequot Press

- Seitenzahl: 168

- Erscheinungstermin: 15. Oktober 2013

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 228mm x 155mm x 9mm

- Gewicht: 327g

- ISBN-13: 9780762782574

- ISBN-10: 0762782579

- Artikelnr.: 37744208

- Herstellerkennzeichnung

- Libri GmbH

- Europaallee 1

- 36244 Bad Hersfeld

- gpsr@libri.de

- Verlag: Globe Pequot Press

- Seitenzahl: 168

- Erscheinungstermin: 15. Oktober 2013

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 228mm x 155mm x 9mm

- Gewicht: 327g

- ISBN-13: 9780762782574

- ISBN-10: 0762782579

- Artikelnr.: 37744208

- Herstellerkennzeichnung

- Libri GmbH

- Europaallee 1

- 36244 Bad Hersfeld

- gpsr@libri.de

Award-winning author Andrew Vietze is a Registered Maine Guide and a seasonal ranger at Baxter State Park. His latest book, Becoming Teddy Roosevelt: How a Maine Guide Inspired America's 26th President, won a silver Independent Publisher's Book Award, was a finalist for a ForeWord Reviews Book of the Year Award, spent weeks on the bestseller list (in Maine), and was honored by decree of the Maine State Legislature. He's written several other books, including the forthcoming tale of the harrowing events on Boon Island (Globe Pequot), and his work has appeared in a wide array of publications, among them Time Out New York, Big Sky Journal, AMC Outdoors, Explore, Crawdaddy!, the New York Times' LifeWire, and Weather.com's Forecast Earth. He's the former Managing Editor of Down East: The Magazine of Maine, has won two International Regional Magazine Awards for history writing, and spends as much time as he can in the woods.

Table of Contents Chapter 1 When Lester Anderson pulled a 97-pound king

salmon out of the Kenai River on an Alaska fishing trip in 1985, he didn't

think much of it. Oh, it was big, he'd spent an hour and a half landing it,

and his brother-in-law Bud almost blew him out of the back of the boat when

he started the motor, but it was just another fish. He and Bud got into the

river, muscled it into their boat, and kept fishing for several hours. Then

he left it on his lawn for a while. By the time someone told him he should

weigh it, because it looked like a record breaker, it had probably lost 3

or 4 pounds due to dehydration. And it still broke the record. Chapter 2

Alfred Dean always said he wanted to catch the biggest fish in the sea. And

he came as close as anyone ever has. The two largest fish are filter

feeders and can't be caught on bait. But the next biggest - the Great White

Shark - could. Remember Jaws? Dean reeled him in on a hand line in 1959.

The Great White hunter has become something of a legend in his native

Australia, and no one will ever catch a bigger Great White than his

2,664-pound giant, because the sharks have become a protected species. Alf

Dean was the world's expert - of the seven largest of these maneaters ever

caught on rod and reel, he bagged six, capturing three international

records. Each weighed more than a ton. Then the Australian angler got his

wish, landing the greatest of the great whites - his shark outweighs the

next biggest fish in the world record book by more than 700 pounds. Chapter

3 Tom Healey probably has some words he'd like to say to Roger Hellen. Less

than a year after setting a world record for Brown Trout on the Manistee

River in Michigan, his fame and glory has fallen. Hellen caught a brownie

in Wisconsin that tied him. The pair now share the record. Healey says, "I

was a retired old guy looking for some peace and quiet on the river. And

then all hell broke loose." As for Hellen, he not only tied a record but he

won more than $10,000 in the process. Chapter 4. Albert McReynolds knows

the sea. He grew up helping his grandfather, a boat captain, on his boat in

Atlantic City, swabbing decks and mending nets and baiting traps - doing

whatever it took to be allowed aboard. Back on land he worked in a

nightclub and became friendly with Frank and Sammy, as in Sinatra and

Davis, Jr. They tried to talk him out of returning to the water, but he

eventually became a captain himself and ran his own boat. When he was 36 he

was fishing from a jetty in the city - in the middle of a Nor'easter - and

landed the biggest striped bass the world has ever known. And then

everything fell apart. McReynolds believes the fish was cursed. He was

accused of lying and cheating and faced death threats. A fellow angler even

pulled a gun on him, he lost friends and money, and the fish was eventually

stolen. "Over a F#$#(#(n' fish," he says. "I didn't catch the devil that

night, the devil caught me." Chapter 5 It sounds like something out of bike

racing or baseball: fish on steroids. Well, not quite, but artificially

enhanced. When Saskatchewan angler Sean Konrad caught a 48-pound rainbow

trout in a Canada Lake in September 09, he reeled in not only a world

record but a big controversy. The rainbow trout at Lake Diefenbaker are

stocked - with a farm-born genetically engineered species bred for size.

Many fishermen say that should disqualify the fish. Konrad, however, knew

this would happen. His twin brother, Adam, held the previous record, caught

in the same place two years earlier. Chapter 6 When fishing for piranha,

it's a good idea not to fall in. Just ask Russell Jensen of the Bronx, who

landed an 8 and half pound black piranha in the Amazon one day in 2009. Not

only does he hold the world record for black piranha but also for the

largest catfish ever caught on rod and reel. He likes them ugly and

dangerous. Chapter 7 On Highway 117 in Jacksonville, Georgia, is an

historic marker. It reads: "Approximately two miles from this spot, on June

2, 1932, George W. Perry, a 19-year-old farm boy, caught what was to become

America's most famous fish." The 22 pound largemouth bass broke the

previous record by more than 2 pounds and has remained king for more than

70 years. It's the record everyone wants to beat. In 2009, Manubu Karita

came close, landing a largemouth of exactly the same size in Lake Biwa,

Shiga, Japan. Chapter 8 Florida fishing guide Bucky Dennis has a bit of the

Ahab in him. The 39-year-old caught a world-record-holding hammerhead shark

off Tampa Bay in 2006, but he wanted more. He's always been competitive. As

a kid, he wrestled. When he was older he raced dirtbikes in amateur

motocross. As an adult he won snook tournaments. And he was determined to

land another world beater. He got his wish in 2009, hauling in a 1060-pound

hammerhead off the coast of his home state. ESPN showed up to take pictures

and he got a slap on the back or two, but the catch was also extremely

controversial. Many believed a shark that large - at that time of year -

was likely to be pregnant, and no one wants little dead hammerheads. Dennis

knew all this but decided to kill the shark so people would believe him -

and in so doing he set off a firestorm of catch-and-release vs. blood sport

arguments. Chapter 9 The record for the muskellunge has been one of the

most hotly contested in all of fishing. Controversies have swirled.

Scientists have tried to use mathematics to estimate the weight of muskies

in old photos. Pinkerton Detectives have been hired to investigate. Books

on conspiracies have been written. But for now Cal Johnson's 67.8 pound

giant, caught just after a storm on Lac Court O'Reilles, Wisconsin, in 1949

reigns supreme. Chapter 10 Mike Livingston had been on the hunt for "super

cows" - tuna weighing more than 300 pounds - for days. He didn't have many

more before he had to leave Mexico and return to his home in Sunland, CA.

And then it hit, the supercow of supercows - a 405.2-pound monster.

Livingston spent more than two hours hauling it in. When the fish came in

to port a massive crowd gathered to see it, and when it landed on the

scales "it was like the SuperBowl." Chapter 11 When Townsend Miller was a

small boy, he hooked a gar while fishing in Texas. The prehistoric-looking

fish launched itself at him and hit him in the belly. Rather than being

repelled, as so many fishermen are by the scaly, long nosed, razor-toothed

monsters, Miller was fascinated. That day began a lifelong love of angling

for gar. A navigator on bombers during World War II, Miller was something

of a renaissance man. He was a stockbroker. Then he moved onto writing,

championing many of the early Texas greats of country music. His love of

music was honest - he was inducted into the Western Swing Hall of Fame

himself. For years he wrote columns for the Austin-American Statesman. He

excelled as a hunter, was an avid baseball fan, and was passionate about

gar fishing at a time when the rest of the world considered the ugly fish

trash. Miller hooked some big ones, including a 7 foot 6, 165 pound

alligator gar. But it was in July of 1954 that he reeled in a world beater

- a 50 pound, 5 oz. longnose, the likes of which the world has never seen

since. Chapter 12 Mabry Harper stares out of the black and white photo with

the hint of a smile on his face, holding his world-record walleye before

him, arms bent at the elbow, hands about shoulder length apart, gripping

the tail and the gills. When he pulled the twenty-five pound fish out of a

Tennessee Lake in August of 1960 he probably had no idea the controversies

it would create. Over the next fifty years, magazines, wildlife agencies,

and lots of jealous anglers would debate whether it was even possible to

land a 25 pound walleye. Few of these members of the perch family seem to

get near 20 pounds, especially in August, when they're swimming hard and

fit, and the one in the photo just doesn't look girthy enough to pack that

kind of weight. But IGFA says the record stands.

salmon out of the Kenai River on an Alaska fishing trip in 1985, he didn't

think much of it. Oh, it was big, he'd spent an hour and a half landing it,

and his brother-in-law Bud almost blew him out of the back of the boat when

he started the motor, but it was just another fish. He and Bud got into the

river, muscled it into their boat, and kept fishing for several hours. Then

he left it on his lawn for a while. By the time someone told him he should

weigh it, because it looked like a record breaker, it had probably lost 3

or 4 pounds due to dehydration. And it still broke the record. Chapter 2

Alfred Dean always said he wanted to catch the biggest fish in the sea. And

he came as close as anyone ever has. The two largest fish are filter

feeders and can't be caught on bait. But the next biggest - the Great White

Shark - could. Remember Jaws? Dean reeled him in on a hand line in 1959.

The Great White hunter has become something of a legend in his native

Australia, and no one will ever catch a bigger Great White than his

2,664-pound giant, because the sharks have become a protected species. Alf

Dean was the world's expert - of the seven largest of these maneaters ever

caught on rod and reel, he bagged six, capturing three international

records. Each weighed more than a ton. Then the Australian angler got his

wish, landing the greatest of the great whites - his shark outweighs the

next biggest fish in the world record book by more than 700 pounds. Chapter

3 Tom Healey probably has some words he'd like to say to Roger Hellen. Less

than a year after setting a world record for Brown Trout on the Manistee

River in Michigan, his fame and glory has fallen. Hellen caught a brownie

in Wisconsin that tied him. The pair now share the record. Healey says, "I

was a retired old guy looking for some peace and quiet on the river. And

then all hell broke loose." As for Hellen, he not only tied a record but he

won more than $10,000 in the process. Chapter 4. Albert McReynolds knows

the sea. He grew up helping his grandfather, a boat captain, on his boat in

Atlantic City, swabbing decks and mending nets and baiting traps - doing

whatever it took to be allowed aboard. Back on land he worked in a

nightclub and became friendly with Frank and Sammy, as in Sinatra and

Davis, Jr. They tried to talk him out of returning to the water, but he

eventually became a captain himself and ran his own boat. When he was 36 he

was fishing from a jetty in the city - in the middle of a Nor'easter - and

landed the biggest striped bass the world has ever known. And then

everything fell apart. McReynolds believes the fish was cursed. He was

accused of lying and cheating and faced death threats. A fellow angler even

pulled a gun on him, he lost friends and money, and the fish was eventually

stolen. "Over a F#$#(#(n' fish," he says. "I didn't catch the devil that

night, the devil caught me." Chapter 5 It sounds like something out of bike

racing or baseball: fish on steroids. Well, not quite, but artificially

enhanced. When Saskatchewan angler Sean Konrad caught a 48-pound rainbow

trout in a Canada Lake in September 09, he reeled in not only a world

record but a big controversy. The rainbow trout at Lake Diefenbaker are

stocked - with a farm-born genetically engineered species bred for size.

Many fishermen say that should disqualify the fish. Konrad, however, knew

this would happen. His twin brother, Adam, held the previous record, caught

in the same place two years earlier. Chapter 6 When fishing for piranha,

it's a good idea not to fall in. Just ask Russell Jensen of the Bronx, who

landed an 8 and half pound black piranha in the Amazon one day in 2009. Not

only does he hold the world record for black piranha but also for the

largest catfish ever caught on rod and reel. He likes them ugly and

dangerous. Chapter 7 On Highway 117 in Jacksonville, Georgia, is an

historic marker. It reads: "Approximately two miles from this spot, on June

2, 1932, George W. Perry, a 19-year-old farm boy, caught what was to become

America's most famous fish." The 22 pound largemouth bass broke the

previous record by more than 2 pounds and has remained king for more than

70 years. It's the record everyone wants to beat. In 2009, Manubu Karita

came close, landing a largemouth of exactly the same size in Lake Biwa,

Shiga, Japan. Chapter 8 Florida fishing guide Bucky Dennis has a bit of the

Ahab in him. The 39-year-old caught a world-record-holding hammerhead shark

off Tampa Bay in 2006, but he wanted more. He's always been competitive. As

a kid, he wrestled. When he was older he raced dirtbikes in amateur

motocross. As an adult he won snook tournaments. And he was determined to

land another world beater. He got his wish in 2009, hauling in a 1060-pound

hammerhead off the coast of his home state. ESPN showed up to take pictures

and he got a slap on the back or two, but the catch was also extremely

controversial. Many believed a shark that large - at that time of year -

was likely to be pregnant, and no one wants little dead hammerheads. Dennis

knew all this but decided to kill the shark so people would believe him -

and in so doing he set off a firestorm of catch-and-release vs. blood sport

arguments. Chapter 9 The record for the muskellunge has been one of the

most hotly contested in all of fishing. Controversies have swirled.

Scientists have tried to use mathematics to estimate the weight of muskies

in old photos. Pinkerton Detectives have been hired to investigate. Books

on conspiracies have been written. But for now Cal Johnson's 67.8 pound

giant, caught just after a storm on Lac Court O'Reilles, Wisconsin, in 1949

reigns supreme. Chapter 10 Mike Livingston had been on the hunt for "super

cows" - tuna weighing more than 300 pounds - for days. He didn't have many

more before he had to leave Mexico and return to his home in Sunland, CA.

And then it hit, the supercow of supercows - a 405.2-pound monster.

Livingston spent more than two hours hauling it in. When the fish came in

to port a massive crowd gathered to see it, and when it landed on the

scales "it was like the SuperBowl." Chapter 11 When Townsend Miller was a

small boy, he hooked a gar while fishing in Texas. The prehistoric-looking

fish launched itself at him and hit him in the belly. Rather than being

repelled, as so many fishermen are by the scaly, long nosed, razor-toothed

monsters, Miller was fascinated. That day began a lifelong love of angling

for gar. A navigator on bombers during World War II, Miller was something

of a renaissance man. He was a stockbroker. Then he moved onto writing,

championing many of the early Texas greats of country music. His love of

music was honest - he was inducted into the Western Swing Hall of Fame

himself. For years he wrote columns for the Austin-American Statesman. He

excelled as a hunter, was an avid baseball fan, and was passionate about

gar fishing at a time when the rest of the world considered the ugly fish

trash. Miller hooked some big ones, including a 7 foot 6, 165 pound

alligator gar. But it was in July of 1954 that he reeled in a world beater

- a 50 pound, 5 oz. longnose, the likes of which the world has never seen

since. Chapter 12 Mabry Harper stares out of the black and white photo with

the hint of a smile on his face, holding his world-record walleye before

him, arms bent at the elbow, hands about shoulder length apart, gripping

the tail and the gills. When he pulled the twenty-five pound fish out of a

Tennessee Lake in August of 1960 he probably had no idea the controversies

it would create. Over the next fifty years, magazines, wildlife agencies,

and lots of jealous anglers would debate whether it was even possible to

land a 25 pound walleye. Few of these members of the perch family seem to

get near 20 pounds, especially in August, when they're swimming hard and

fit, and the one in the photo just doesn't look girthy enough to pack that

kind of weight. But IGFA says the record stands.

Table of Contents Chapter 1 When Lester Anderson pulled a 97-pound king

salmon out of the Kenai River on an Alaska fishing trip in 1985, he didn't

think much of it. Oh, it was big, he'd spent an hour and a half landing it,

and his brother-in-law Bud almost blew him out of the back of the boat when

he started the motor, but it was just another fish. He and Bud got into the

river, muscled it into their boat, and kept fishing for several hours. Then

he left it on his lawn for a while. By the time someone told him he should

weigh it, because it looked like a record breaker, it had probably lost 3

or 4 pounds due to dehydration. And it still broke the record. Chapter 2

Alfred Dean always said he wanted to catch the biggest fish in the sea. And

he came as close as anyone ever has. The two largest fish are filter

feeders and can't be caught on bait. But the next biggest - the Great White

Shark - could. Remember Jaws? Dean reeled him in on a hand line in 1959.

The Great White hunter has become something of a legend in his native

Australia, and no one will ever catch a bigger Great White than his

2,664-pound giant, because the sharks have become a protected species. Alf

Dean was the world's expert - of the seven largest of these maneaters ever

caught on rod and reel, he bagged six, capturing three international

records. Each weighed more than a ton. Then the Australian angler got his

wish, landing the greatest of the great whites - his shark outweighs the

next biggest fish in the world record book by more than 700 pounds. Chapter

3 Tom Healey probably has some words he'd like to say to Roger Hellen. Less

than a year after setting a world record for Brown Trout on the Manistee

River in Michigan, his fame and glory has fallen. Hellen caught a brownie

in Wisconsin that tied him. The pair now share the record. Healey says, "I

was a retired old guy looking for some peace and quiet on the river. And

then all hell broke loose." As for Hellen, he not only tied a record but he

won more than $10,000 in the process. Chapter 4. Albert McReynolds knows

the sea. He grew up helping his grandfather, a boat captain, on his boat in

Atlantic City, swabbing decks and mending nets and baiting traps - doing

whatever it took to be allowed aboard. Back on land he worked in a

nightclub and became friendly with Frank and Sammy, as in Sinatra and

Davis, Jr. They tried to talk him out of returning to the water, but he

eventually became a captain himself and ran his own boat. When he was 36 he

was fishing from a jetty in the city - in the middle of a Nor'easter - and

landed the biggest striped bass the world has ever known. And then

everything fell apart. McReynolds believes the fish was cursed. He was

accused of lying and cheating and faced death threats. A fellow angler even

pulled a gun on him, he lost friends and money, and the fish was eventually

stolen. "Over a F#$#(#(n' fish," he says. "I didn't catch the devil that

night, the devil caught me." Chapter 5 It sounds like something out of bike

racing or baseball: fish on steroids. Well, not quite, but artificially

enhanced. When Saskatchewan angler Sean Konrad caught a 48-pound rainbow

trout in a Canada Lake in September 09, he reeled in not only a world

record but a big controversy. The rainbow trout at Lake Diefenbaker are

stocked - with a farm-born genetically engineered species bred for size.

Many fishermen say that should disqualify the fish. Konrad, however, knew

this would happen. His twin brother, Adam, held the previous record, caught

in the same place two years earlier. Chapter 6 When fishing for piranha,

it's a good idea not to fall in. Just ask Russell Jensen of the Bronx, who

landed an 8 and half pound black piranha in the Amazon one day in 2009. Not

only does he hold the world record for black piranha but also for the

largest catfish ever caught on rod and reel. He likes them ugly and

dangerous. Chapter 7 On Highway 117 in Jacksonville, Georgia, is an

historic marker. It reads: "Approximately two miles from this spot, on June

2, 1932, George W. Perry, a 19-year-old farm boy, caught what was to become

America's most famous fish." The 22 pound largemouth bass broke the

previous record by more than 2 pounds and has remained king for more than

70 years. It's the record everyone wants to beat. In 2009, Manubu Karita

came close, landing a largemouth of exactly the same size in Lake Biwa,

Shiga, Japan. Chapter 8 Florida fishing guide Bucky Dennis has a bit of the

Ahab in him. The 39-year-old caught a world-record-holding hammerhead shark

off Tampa Bay in 2006, but he wanted more. He's always been competitive. As

a kid, he wrestled. When he was older he raced dirtbikes in amateur

motocross. As an adult he won snook tournaments. And he was determined to

land another world beater. He got his wish in 2009, hauling in a 1060-pound

hammerhead off the coast of his home state. ESPN showed up to take pictures

and he got a slap on the back or two, but the catch was also extremely

controversial. Many believed a shark that large - at that time of year -

was likely to be pregnant, and no one wants little dead hammerheads. Dennis

knew all this but decided to kill the shark so people would believe him -

and in so doing he set off a firestorm of catch-and-release vs. blood sport

arguments. Chapter 9 The record for the muskellunge has been one of the

most hotly contested in all of fishing. Controversies have swirled.

Scientists have tried to use mathematics to estimate the weight of muskies

in old photos. Pinkerton Detectives have been hired to investigate. Books

on conspiracies have been written. But for now Cal Johnson's 67.8 pound

giant, caught just after a storm on Lac Court O'Reilles, Wisconsin, in 1949

reigns supreme. Chapter 10 Mike Livingston had been on the hunt for "super

cows" - tuna weighing more than 300 pounds - for days. He didn't have many

more before he had to leave Mexico and return to his home in Sunland, CA.

And then it hit, the supercow of supercows - a 405.2-pound monster.

Livingston spent more than two hours hauling it in. When the fish came in

to port a massive crowd gathered to see it, and when it landed on the

scales "it was like the SuperBowl." Chapter 11 When Townsend Miller was a

small boy, he hooked a gar while fishing in Texas. The prehistoric-looking

fish launched itself at him and hit him in the belly. Rather than being

repelled, as so many fishermen are by the scaly, long nosed, razor-toothed

monsters, Miller was fascinated. That day began a lifelong love of angling

for gar. A navigator on bombers during World War II, Miller was something

of a renaissance man. He was a stockbroker. Then he moved onto writing,

championing many of the early Texas greats of country music. His love of

music was honest - he was inducted into the Western Swing Hall of Fame

himself. For years he wrote columns for the Austin-American Statesman. He

excelled as a hunter, was an avid baseball fan, and was passionate about

gar fishing at a time when the rest of the world considered the ugly fish

trash. Miller hooked some big ones, including a 7 foot 6, 165 pound

alligator gar. But it was in July of 1954 that he reeled in a world beater

- a 50 pound, 5 oz. longnose, the likes of which the world has never seen

since. Chapter 12 Mabry Harper stares out of the black and white photo with

the hint of a smile on his face, holding his world-record walleye before

him, arms bent at the elbow, hands about shoulder length apart, gripping

the tail and the gills. When he pulled the twenty-five pound fish out of a

Tennessee Lake in August of 1960 he probably had no idea the controversies

it would create. Over the next fifty years, magazines, wildlife agencies,

and lots of jealous anglers would debate whether it was even possible to

land a 25 pound walleye. Few of these members of the perch family seem to

get near 20 pounds, especially in August, when they're swimming hard and

fit, and the one in the photo just doesn't look girthy enough to pack that

kind of weight. But IGFA says the record stands.

salmon out of the Kenai River on an Alaska fishing trip in 1985, he didn't

think much of it. Oh, it was big, he'd spent an hour and a half landing it,

and his brother-in-law Bud almost blew him out of the back of the boat when

he started the motor, but it was just another fish. He and Bud got into the

river, muscled it into their boat, and kept fishing for several hours. Then

he left it on his lawn for a while. By the time someone told him he should

weigh it, because it looked like a record breaker, it had probably lost 3

or 4 pounds due to dehydration. And it still broke the record. Chapter 2

Alfred Dean always said he wanted to catch the biggest fish in the sea. And

he came as close as anyone ever has. The two largest fish are filter

feeders and can't be caught on bait. But the next biggest - the Great White

Shark - could. Remember Jaws? Dean reeled him in on a hand line in 1959.

The Great White hunter has become something of a legend in his native

Australia, and no one will ever catch a bigger Great White than his

2,664-pound giant, because the sharks have become a protected species. Alf

Dean was the world's expert - of the seven largest of these maneaters ever

caught on rod and reel, he bagged six, capturing three international

records. Each weighed more than a ton. Then the Australian angler got his

wish, landing the greatest of the great whites - his shark outweighs the

next biggest fish in the world record book by more than 700 pounds. Chapter

3 Tom Healey probably has some words he'd like to say to Roger Hellen. Less

than a year after setting a world record for Brown Trout on the Manistee

River in Michigan, his fame and glory has fallen. Hellen caught a brownie

in Wisconsin that tied him. The pair now share the record. Healey says, "I

was a retired old guy looking for some peace and quiet on the river. And

then all hell broke loose." As for Hellen, he not only tied a record but he

won more than $10,000 in the process. Chapter 4. Albert McReynolds knows

the sea. He grew up helping his grandfather, a boat captain, on his boat in

Atlantic City, swabbing decks and mending nets and baiting traps - doing

whatever it took to be allowed aboard. Back on land he worked in a

nightclub and became friendly with Frank and Sammy, as in Sinatra and

Davis, Jr. They tried to talk him out of returning to the water, but he

eventually became a captain himself and ran his own boat. When he was 36 he

was fishing from a jetty in the city - in the middle of a Nor'easter - and

landed the biggest striped bass the world has ever known. And then

everything fell apart. McReynolds believes the fish was cursed. He was

accused of lying and cheating and faced death threats. A fellow angler even

pulled a gun on him, he lost friends and money, and the fish was eventually

stolen. "Over a F#$#(#(n' fish," he says. "I didn't catch the devil that

night, the devil caught me." Chapter 5 It sounds like something out of bike

racing or baseball: fish on steroids. Well, not quite, but artificially

enhanced. When Saskatchewan angler Sean Konrad caught a 48-pound rainbow

trout in a Canada Lake in September 09, he reeled in not only a world

record but a big controversy. The rainbow trout at Lake Diefenbaker are

stocked - with a farm-born genetically engineered species bred for size.

Many fishermen say that should disqualify the fish. Konrad, however, knew

this would happen. His twin brother, Adam, held the previous record, caught

in the same place two years earlier. Chapter 6 When fishing for piranha,

it's a good idea not to fall in. Just ask Russell Jensen of the Bronx, who

landed an 8 and half pound black piranha in the Amazon one day in 2009. Not

only does he hold the world record for black piranha but also for the

largest catfish ever caught on rod and reel. He likes them ugly and

dangerous. Chapter 7 On Highway 117 in Jacksonville, Georgia, is an

historic marker. It reads: "Approximately two miles from this spot, on June

2, 1932, George W. Perry, a 19-year-old farm boy, caught what was to become

America's most famous fish." The 22 pound largemouth bass broke the

previous record by more than 2 pounds and has remained king for more than

70 years. It's the record everyone wants to beat. In 2009, Manubu Karita

came close, landing a largemouth of exactly the same size in Lake Biwa,

Shiga, Japan. Chapter 8 Florida fishing guide Bucky Dennis has a bit of the

Ahab in him. The 39-year-old caught a world-record-holding hammerhead shark

off Tampa Bay in 2006, but he wanted more. He's always been competitive. As

a kid, he wrestled. When he was older he raced dirtbikes in amateur

motocross. As an adult he won snook tournaments. And he was determined to

land another world beater. He got his wish in 2009, hauling in a 1060-pound

hammerhead off the coast of his home state. ESPN showed up to take pictures

and he got a slap on the back or two, but the catch was also extremely

controversial. Many believed a shark that large - at that time of year -

was likely to be pregnant, and no one wants little dead hammerheads. Dennis

knew all this but decided to kill the shark so people would believe him -

and in so doing he set off a firestorm of catch-and-release vs. blood sport

arguments. Chapter 9 The record for the muskellunge has been one of the

most hotly contested in all of fishing. Controversies have swirled.

Scientists have tried to use mathematics to estimate the weight of muskies

in old photos. Pinkerton Detectives have been hired to investigate. Books

on conspiracies have been written. But for now Cal Johnson's 67.8 pound

giant, caught just after a storm on Lac Court O'Reilles, Wisconsin, in 1949

reigns supreme. Chapter 10 Mike Livingston had been on the hunt for "super

cows" - tuna weighing more than 300 pounds - for days. He didn't have many

more before he had to leave Mexico and return to his home in Sunland, CA.

And then it hit, the supercow of supercows - a 405.2-pound monster.

Livingston spent more than two hours hauling it in. When the fish came in

to port a massive crowd gathered to see it, and when it landed on the

scales "it was like the SuperBowl." Chapter 11 When Townsend Miller was a

small boy, he hooked a gar while fishing in Texas. The prehistoric-looking

fish launched itself at him and hit him in the belly. Rather than being

repelled, as so many fishermen are by the scaly, long nosed, razor-toothed

monsters, Miller was fascinated. That day began a lifelong love of angling

for gar. A navigator on bombers during World War II, Miller was something

of a renaissance man. He was a stockbroker. Then he moved onto writing,

championing many of the early Texas greats of country music. His love of

music was honest - he was inducted into the Western Swing Hall of Fame

himself. For years he wrote columns for the Austin-American Statesman. He

excelled as a hunter, was an avid baseball fan, and was passionate about

gar fishing at a time when the rest of the world considered the ugly fish

trash. Miller hooked some big ones, including a 7 foot 6, 165 pound

alligator gar. But it was in July of 1954 that he reeled in a world beater

- a 50 pound, 5 oz. longnose, the likes of which the world has never seen

since. Chapter 12 Mabry Harper stares out of the black and white photo with

the hint of a smile on his face, holding his world-record walleye before

him, arms bent at the elbow, hands about shoulder length apart, gripping

the tail and the gills. When he pulled the twenty-five pound fish out of a

Tennessee Lake in August of 1960 he probably had no idea the controversies

it would create. Over the next fifty years, magazines, wildlife agencies,

and lots of jealous anglers would debate whether it was even possible to

land a 25 pound walleye. Few of these members of the perch family seem to

get near 20 pounds, especially in August, when they're swimming hard and

fit, and the one in the photo just doesn't look girthy enough to pack that

kind of weight. But IGFA says the record stands.