17,99 €

inkl. MwSt.

Versandfertig in über 4 Wochen

9 °P sammeln

- Broschiertes Buch

- Merkliste

- Auf die Merkliste

- Bewerten Bewerten

- Teilen

- Produkt teilen

- Produkterinnerung

- Produkterinnerung

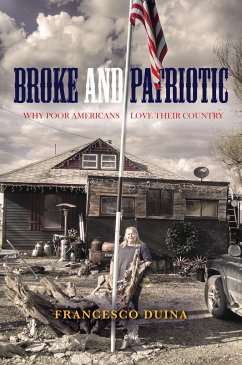

Francesco Duina is Professor of Sociology at Bates College, as well as Honorary Professor of Sociology at the University of British Columbia and Visiting Professor of Business and Politics at the Copenhagen Business School. He is the author of several books, including Winning: Reflections on an American Obsession (2011).

Andere Kunden interessierten sich auch für

![Patriotic Correctness Patriotic Correctness]() John K. WilsonPatriotic Correctness83,99 €

John K. WilsonPatriotic Correctness83,99 €![The Women Who Broke All the Rules The Women Who Broke All the Rules]() Susan B EvansThe Women Who Broke All the Rules19,99 €

Susan B EvansThe Women Who Broke All the Rules19,99 €![Foreclosed America Foreclosed America]() Isaac MartinForeclosed America17,99 €

Isaac MartinForeclosed America17,99 €![Myth of the Social Volcano Myth of the Social Volcano]() Martin WhyteMyth of the Social Volcano33,99 €

Martin WhyteMyth of the Social Volcano33,99 €![Burden of Support Burden of Support]() David E Hayes-BautistaBurden of Support33,99 €

David E Hayes-BautistaBurden of Support33,99 €![Demographic Engineering Demographic Engineering]() Paul MorlandDemographic Engineering74,99 €

Paul MorlandDemographic Engineering74,99 €![The Myth of the Age of Entitlement The Myth of the Age of Entitlement]() James CairnsThe Myth of the Age of Entitlement42,99 €

James CairnsThe Myth of the Age of Entitlement42,99 €-

-

Francesco Duina is Professor of Sociology at Bates College, as well as Honorary Professor of Sociology at the University of British Columbia and Visiting Professor of Business and Politics at the Copenhagen Business School. He is the author of several books, including Winning: Reflections on an American Obsession (2011).

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Produktdetails

- Produktdetails

- Verlag: Stanford University Press

- Seitenzahl: 240

- Erscheinungstermin: 16. Oktober 2018

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 216mm x 140mm x 14mm

- Gewicht: 308g

- ISBN-13: 9781503608214

- ISBN-10: 1503608212

- Artikelnr.: 52424477

- Herstellerkennzeichnung

- Libri GmbH

- Europaallee 1

- 36244 Bad Hersfeld

- gpsr@libri.de

- Verlag: Stanford University Press

- Seitenzahl: 240

- Erscheinungstermin: 16. Oktober 2018

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 216mm x 140mm x 14mm

- Gewicht: 308g

- ISBN-13: 9781503608214

- ISBN-10: 1503608212

- Artikelnr.: 52424477

- Herstellerkennzeichnung

- Libri GmbH

- Europaallee 1

- 36244 Bad Hersfeld

- gpsr@libri.de

Francesco Duina is Professor of Sociology at Bates College, as well as Honorary Professor of Sociology at the University of British Columbia and Visiting Professor of Business and Politics at the Copenhagen Business School. He is the author of several books, including Winning: Reflections on an American Obsession (2011).

Contents and Abstracts

1The Prehistoric Roots of the Modern Mind

chapter abstract

This chapter presents an overview of the development and architecture of

the human brain, and shows what evolutionary history has to do with the

nature of cognition today. Drawing on the perspectives and techniques of

evolutionary psychology, it pursues the following questions: (1) Given our

ancestral world, what kinds of mental structures and functions should we

expect to find in the brain, and do we? and (2) What roles do mental

structures and functions formed in the Pleistocene world continue to play

in "modern" minds? In the course of the discussion, it also outlines

contemporary models of the mind-from the "blank slate" view to the idea of

massive modularity-and surveys the range of intuitive knowledge (e.g.,

intuitive biology, intuitive physics, and intuitive psychology) and innate

cognitive processes that both shape and constrain human thought.

1A People's Country

chapter abstract

Chapter 1 introduces the key puzzle of the book-why are poor Americans

patriotic?-and explains why we should try to answer it. Much, in fact,

depends on that patriotism: the social order, the nature of inequality in

the country, military recruitment, and America's sense of self and identity

both at home and on the world stage. The patriotism of the poor can also be

politically very salient, as seen during the presidential elections of 2016

and Donald Trump's victory. The chapter explains that extensive in-depth

interviews were carried out in Montana and Alabama and summarizes the

findings: America is a place of hope, the "land of milk and honey," and a

country of freedom. Americans belong to the country; more important,

however, the country still belongs to Americans. With much else in life a

struggle, being American offers invaluable meaning and dignity.

2Broke and Patriotic

chapter abstract

Chapter 2 presents evidence that poor Americans are by many measures, (such

as Social Security benefits, intergenerational mobility prospects, working

hours, and income and wealth gaps relative to middle and upper classes)

worse off than the poor in other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD) countries. The American Dream is eluding them. At the

same time, the American poor (even if we control for race, gender, or other

dimensions) are extraordinarily patriotic. Indeed, their patriotism matches

or exceeds that of the poor in other OECD countries and is equal if not

superior to the patriotism of wealthier Americans. Data come from the World

Values Survey, the General Social Survey, and other sources. Why do the

poor hold such high levels of patriotism?

3Heading to Alabama and Montana

chapter abstract

Chapter 3 notes that we know little about the patriotism of the poor.

Research on related topics, however, can offer us initial potential

insights. The chapter thus examines works on the origins, including the

popular roots, and evolution of American patriotism through time. The

chapter examines research on the patriotism of different types of

marginalized Americans (women, African Americans, Native Americans) and

considers research on social cohesion. It identifies the initial hypotheses

for the book and then specifies the research methods used for

investigation: for example, selection of sites (Alabama and Montana),

selection of interviewees, and survey questions used. The chapter refers

readers to the Appendix for further methodological details.

4The Last Hope

chapter abstract

Chapter 4 explores the sentiments, held by most interviewees, that America

is an exceptional, even transcendental, country: a place designed and

intended to offer deliverance from the ills that have plagued humanity

throughout history to this very day. America, in a word, represents hope,

both for humanity and for each individual person in the country. The

interviewees evoked pictures of oppressive and destitute places when

describing other countries. America offers reprieve and the possibility of

a better future. The idea of exceptionality was further reinforced by a

belief that, while God is kind and loves everyone equally, he holds America

in a special place in his heart: America is God's country. And with this

there was also an almost tragic sense, described by several, that one has

to believe in America: when all else seems to be a struggle, faith in

country, and in America in particular, is a must.

5The Land of Milk and Honey

chapter abstract

In Chapter 5, many of the people interviewed, despite their own lives'

often difficult trajectories, took pride in America's great wealth and

what, they felt, it means for the country's poor: an abundance of riches

that allows everyone to survive, a feeling that one is being taken care of,

and the conviction that anything is possible in America: despite their own

lives' often difficult trajectories. America, they asserted, despite all

their troubles, is the "land of milk and honey." Many of the interviewees

spoke of the limitations of other countries: run-down, unable to provide

for their people, and oppressive. Everyone still wants to come to the

United States, they said. The country's natural beauty may play a role,

too. Many expressed contentment with their lot. There were differences

between interviewees in Alabama and Montana.

6Freedom

chapter abstract

Chapter 6 discusses how "freedom" was the word that nearly all interviewees

mentioned when accounting for their love of the United States. Questions of

income, social status, or other metrics of personal success were secondary

and often irrelevant. Freedom is at the heart of the American social

contract. Freedom means individual self-determination, both physical and

mental. Those in Montana infused this narrative with considerable

libertarian themes; black interviewees in Alabama tended to point to

progress in racial relations. Only America guarantees the right to bear

arms. This is a matter of self-protection and rebellion against tyranny.

But with guns one can also hunt and feed one's family. Many stressed that

America's freedom was fought for, at great cost, by generations of

Americans. To these we should add more localized patriotic narratives: a

Confederate view of heritage in Alabama and an antigovernment version in

Montana.

7Reconciling Poverty and Patriotism

chapter abstract

Did the interviewees feel a contradiction between their difficult life

situations and love of country? Chapter 7 notes that there was no puzzle in

their minds. They talked about the fairness of outcomes in life, their

sense that new opportunities were about to come along (especially if one is

walking with God), a conviction that everyone is worth the same regardless

of wealth, and, finally, that the United States is really the only country

they know. Taken together, these answers help complete the picture of the

depth and coherence of the patriotism of America's poor. One's precarious

circumstances are no grounds for doubting the greatness of the country.

8An Unshakable Bond

chapter abstract

Chapter 8 summarizes the key findings from the interviews. It emphasizes

the strong, personal, and multifaceted bonds between America's worst-off

and their country. The chapter concludes by reflecting on three broader

themes: inequality and politics in America, the possible evolution and uses

of the patriotism of America's poor (with a specific reference to Donald

Trump's victory in the 2016 presidential election), and the nature of

patriotism across different economic classes in America.

1The Prehistoric Roots of the Modern Mind

chapter abstract

This chapter presents an overview of the development and architecture of

the human brain, and shows what evolutionary history has to do with the

nature of cognition today. Drawing on the perspectives and techniques of

evolutionary psychology, it pursues the following questions: (1) Given our

ancestral world, what kinds of mental structures and functions should we

expect to find in the brain, and do we? and (2) What roles do mental

structures and functions formed in the Pleistocene world continue to play

in "modern" minds? In the course of the discussion, it also outlines

contemporary models of the mind-from the "blank slate" view to the idea of

massive modularity-and surveys the range of intuitive knowledge (e.g.,

intuitive biology, intuitive physics, and intuitive psychology) and innate

cognitive processes that both shape and constrain human thought.

1A People's Country

chapter abstract

Chapter 1 introduces the key puzzle of the book-why are poor Americans

patriotic?-and explains why we should try to answer it. Much, in fact,

depends on that patriotism: the social order, the nature of inequality in

the country, military recruitment, and America's sense of self and identity

both at home and on the world stage. The patriotism of the poor can also be

politically very salient, as seen during the presidential elections of 2016

and Donald Trump's victory. The chapter explains that extensive in-depth

interviews were carried out in Montana and Alabama and summarizes the

findings: America is a place of hope, the "land of milk and honey," and a

country of freedom. Americans belong to the country; more important,

however, the country still belongs to Americans. With much else in life a

struggle, being American offers invaluable meaning and dignity.

2Broke and Patriotic

chapter abstract

Chapter 2 presents evidence that poor Americans are by many measures, (such

as Social Security benefits, intergenerational mobility prospects, working

hours, and income and wealth gaps relative to middle and upper classes)

worse off than the poor in other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD) countries. The American Dream is eluding them. At the

same time, the American poor (even if we control for race, gender, or other

dimensions) are extraordinarily patriotic. Indeed, their patriotism matches

or exceeds that of the poor in other OECD countries and is equal if not

superior to the patriotism of wealthier Americans. Data come from the World

Values Survey, the General Social Survey, and other sources. Why do the

poor hold such high levels of patriotism?

3Heading to Alabama and Montana

chapter abstract

Chapter 3 notes that we know little about the patriotism of the poor.

Research on related topics, however, can offer us initial potential

insights. The chapter thus examines works on the origins, including the

popular roots, and evolution of American patriotism through time. The

chapter examines research on the patriotism of different types of

marginalized Americans (women, African Americans, Native Americans) and

considers research on social cohesion. It identifies the initial hypotheses

for the book and then specifies the research methods used for

investigation: for example, selection of sites (Alabama and Montana),

selection of interviewees, and survey questions used. The chapter refers

readers to the Appendix for further methodological details.

4The Last Hope

chapter abstract

Chapter 4 explores the sentiments, held by most interviewees, that America

is an exceptional, even transcendental, country: a place designed and

intended to offer deliverance from the ills that have plagued humanity

throughout history to this very day. America, in a word, represents hope,

both for humanity and for each individual person in the country. The

interviewees evoked pictures of oppressive and destitute places when

describing other countries. America offers reprieve and the possibility of

a better future. The idea of exceptionality was further reinforced by a

belief that, while God is kind and loves everyone equally, he holds America

in a special place in his heart: America is God's country. And with this

there was also an almost tragic sense, described by several, that one has

to believe in America: when all else seems to be a struggle, faith in

country, and in America in particular, is a must.

5The Land of Milk and Honey

chapter abstract

In Chapter 5, many of the people interviewed, despite their own lives'

often difficult trajectories, took pride in America's great wealth and

what, they felt, it means for the country's poor: an abundance of riches

that allows everyone to survive, a feeling that one is being taken care of,

and the conviction that anything is possible in America: despite their own

lives' often difficult trajectories. America, they asserted, despite all

their troubles, is the "land of milk and honey." Many of the interviewees

spoke of the limitations of other countries: run-down, unable to provide

for their people, and oppressive. Everyone still wants to come to the

United States, they said. The country's natural beauty may play a role,

too. Many expressed contentment with their lot. There were differences

between interviewees in Alabama and Montana.

6Freedom

chapter abstract

Chapter 6 discusses how "freedom" was the word that nearly all interviewees

mentioned when accounting for their love of the United States. Questions of

income, social status, or other metrics of personal success were secondary

and often irrelevant. Freedom is at the heart of the American social

contract. Freedom means individual self-determination, both physical and

mental. Those in Montana infused this narrative with considerable

libertarian themes; black interviewees in Alabama tended to point to

progress in racial relations. Only America guarantees the right to bear

arms. This is a matter of self-protection and rebellion against tyranny.

But with guns one can also hunt and feed one's family. Many stressed that

America's freedom was fought for, at great cost, by generations of

Americans. To these we should add more localized patriotic narratives: a

Confederate view of heritage in Alabama and an antigovernment version in

Montana.

7Reconciling Poverty and Patriotism

chapter abstract

Did the interviewees feel a contradiction between their difficult life

situations and love of country? Chapter 7 notes that there was no puzzle in

their minds. They talked about the fairness of outcomes in life, their

sense that new opportunities were about to come along (especially if one is

walking with God), a conviction that everyone is worth the same regardless

of wealth, and, finally, that the United States is really the only country

they know. Taken together, these answers help complete the picture of the

depth and coherence of the patriotism of America's poor. One's precarious

circumstances are no grounds for doubting the greatness of the country.

8An Unshakable Bond

chapter abstract

Chapter 8 summarizes the key findings from the interviews. It emphasizes

the strong, personal, and multifaceted bonds between America's worst-off

and their country. The chapter concludes by reflecting on three broader

themes: inequality and politics in America, the possible evolution and uses

of the patriotism of America's poor (with a specific reference to Donald

Trump's victory in the 2016 presidential election), and the nature of

patriotism across different economic classes in America.

Contents and Abstracts

1The Prehistoric Roots of the Modern Mind

chapter abstract

This chapter presents an overview of the development and architecture of

the human brain, and shows what evolutionary history has to do with the

nature of cognition today. Drawing on the perspectives and techniques of

evolutionary psychology, it pursues the following questions: (1) Given our

ancestral world, what kinds of mental structures and functions should we

expect to find in the brain, and do we? and (2) What roles do mental

structures and functions formed in the Pleistocene world continue to play

in "modern" minds? In the course of the discussion, it also outlines

contemporary models of the mind-from the "blank slate" view to the idea of

massive modularity-and surveys the range of intuitive knowledge (e.g.,

intuitive biology, intuitive physics, and intuitive psychology) and innate

cognitive processes that both shape and constrain human thought.

1A People's Country

chapter abstract

Chapter 1 introduces the key puzzle of the book-why are poor Americans

patriotic?-and explains why we should try to answer it. Much, in fact,

depends on that patriotism: the social order, the nature of inequality in

the country, military recruitment, and America's sense of self and identity

both at home and on the world stage. The patriotism of the poor can also be

politically very salient, as seen during the presidential elections of 2016

and Donald Trump's victory. The chapter explains that extensive in-depth

interviews were carried out in Montana and Alabama and summarizes the

findings: America is a place of hope, the "land of milk and honey," and a

country of freedom. Americans belong to the country; more important,

however, the country still belongs to Americans. With much else in life a

struggle, being American offers invaluable meaning and dignity.

2Broke and Patriotic

chapter abstract

Chapter 2 presents evidence that poor Americans are by many measures, (such

as Social Security benefits, intergenerational mobility prospects, working

hours, and income and wealth gaps relative to middle and upper classes)

worse off than the poor in other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD) countries. The American Dream is eluding them. At the

same time, the American poor (even if we control for race, gender, or other

dimensions) are extraordinarily patriotic. Indeed, their patriotism matches

or exceeds that of the poor in other OECD countries and is equal if not

superior to the patriotism of wealthier Americans. Data come from the World

Values Survey, the General Social Survey, and other sources. Why do the

poor hold such high levels of patriotism?

3Heading to Alabama and Montana

chapter abstract

Chapter 3 notes that we know little about the patriotism of the poor.

Research on related topics, however, can offer us initial potential

insights. The chapter thus examines works on the origins, including the

popular roots, and evolution of American patriotism through time. The

chapter examines research on the patriotism of different types of

marginalized Americans (women, African Americans, Native Americans) and

considers research on social cohesion. It identifies the initial hypotheses

for the book and then specifies the research methods used for

investigation: for example, selection of sites (Alabama and Montana),

selection of interviewees, and survey questions used. The chapter refers

readers to the Appendix for further methodological details.

4The Last Hope

chapter abstract

Chapter 4 explores the sentiments, held by most interviewees, that America

is an exceptional, even transcendental, country: a place designed and

intended to offer deliverance from the ills that have plagued humanity

throughout history to this very day. America, in a word, represents hope,

both for humanity and for each individual person in the country. The

interviewees evoked pictures of oppressive and destitute places when

describing other countries. America offers reprieve and the possibility of

a better future. The idea of exceptionality was further reinforced by a

belief that, while God is kind and loves everyone equally, he holds America

in a special place in his heart: America is God's country. And with this

there was also an almost tragic sense, described by several, that one has

to believe in America: when all else seems to be a struggle, faith in

country, and in America in particular, is a must.

5The Land of Milk and Honey

chapter abstract

In Chapter 5, many of the people interviewed, despite their own lives'

often difficult trajectories, took pride in America's great wealth and

what, they felt, it means for the country's poor: an abundance of riches

that allows everyone to survive, a feeling that one is being taken care of,

and the conviction that anything is possible in America: despite their own

lives' often difficult trajectories. America, they asserted, despite all

their troubles, is the "land of milk and honey." Many of the interviewees

spoke of the limitations of other countries: run-down, unable to provide

for their people, and oppressive. Everyone still wants to come to the

United States, they said. The country's natural beauty may play a role,

too. Many expressed contentment with their lot. There were differences

between interviewees in Alabama and Montana.

6Freedom

chapter abstract

Chapter 6 discusses how "freedom" was the word that nearly all interviewees

mentioned when accounting for their love of the United States. Questions of

income, social status, or other metrics of personal success were secondary

and often irrelevant. Freedom is at the heart of the American social

contract. Freedom means individual self-determination, both physical and

mental. Those in Montana infused this narrative with considerable

libertarian themes; black interviewees in Alabama tended to point to

progress in racial relations. Only America guarantees the right to bear

arms. This is a matter of self-protection and rebellion against tyranny.

But with guns one can also hunt and feed one's family. Many stressed that

America's freedom was fought for, at great cost, by generations of

Americans. To these we should add more localized patriotic narratives: a

Confederate view of heritage in Alabama and an antigovernment version in

Montana.

7Reconciling Poverty and Patriotism

chapter abstract

Did the interviewees feel a contradiction between their difficult life

situations and love of country? Chapter 7 notes that there was no puzzle in

their minds. They talked about the fairness of outcomes in life, their

sense that new opportunities were about to come along (especially if one is

walking with God), a conviction that everyone is worth the same regardless

of wealth, and, finally, that the United States is really the only country

they know. Taken together, these answers help complete the picture of the

depth and coherence of the patriotism of America's poor. One's precarious

circumstances are no grounds for doubting the greatness of the country.

8An Unshakable Bond

chapter abstract

Chapter 8 summarizes the key findings from the interviews. It emphasizes

the strong, personal, and multifaceted bonds between America's worst-off

and their country. The chapter concludes by reflecting on three broader

themes: inequality and politics in America, the possible evolution and uses

of the patriotism of America's poor (with a specific reference to Donald

Trump's victory in the 2016 presidential election), and the nature of

patriotism across different economic classes in America.

1The Prehistoric Roots of the Modern Mind

chapter abstract

This chapter presents an overview of the development and architecture of

the human brain, and shows what evolutionary history has to do with the

nature of cognition today. Drawing on the perspectives and techniques of

evolutionary psychology, it pursues the following questions: (1) Given our

ancestral world, what kinds of mental structures and functions should we

expect to find in the brain, and do we? and (2) What roles do mental

structures and functions formed in the Pleistocene world continue to play

in "modern" minds? In the course of the discussion, it also outlines

contemporary models of the mind-from the "blank slate" view to the idea of

massive modularity-and surveys the range of intuitive knowledge (e.g.,

intuitive biology, intuitive physics, and intuitive psychology) and innate

cognitive processes that both shape and constrain human thought.

1A People's Country

chapter abstract

Chapter 1 introduces the key puzzle of the book-why are poor Americans

patriotic?-and explains why we should try to answer it. Much, in fact,

depends on that patriotism: the social order, the nature of inequality in

the country, military recruitment, and America's sense of self and identity

both at home and on the world stage. The patriotism of the poor can also be

politically very salient, as seen during the presidential elections of 2016

and Donald Trump's victory. The chapter explains that extensive in-depth

interviews were carried out in Montana and Alabama and summarizes the

findings: America is a place of hope, the "land of milk and honey," and a

country of freedom. Americans belong to the country; more important,

however, the country still belongs to Americans. With much else in life a

struggle, being American offers invaluable meaning and dignity.

2Broke and Patriotic

chapter abstract

Chapter 2 presents evidence that poor Americans are by many measures, (such

as Social Security benefits, intergenerational mobility prospects, working

hours, and income and wealth gaps relative to middle and upper classes)

worse off than the poor in other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD) countries. The American Dream is eluding them. At the

same time, the American poor (even if we control for race, gender, or other

dimensions) are extraordinarily patriotic. Indeed, their patriotism matches

or exceeds that of the poor in other OECD countries and is equal if not

superior to the patriotism of wealthier Americans. Data come from the World

Values Survey, the General Social Survey, and other sources. Why do the

poor hold such high levels of patriotism?

3Heading to Alabama and Montana

chapter abstract

Chapter 3 notes that we know little about the patriotism of the poor.

Research on related topics, however, can offer us initial potential

insights. The chapter thus examines works on the origins, including the

popular roots, and evolution of American patriotism through time. The

chapter examines research on the patriotism of different types of

marginalized Americans (women, African Americans, Native Americans) and

considers research on social cohesion. It identifies the initial hypotheses

for the book and then specifies the research methods used for

investigation: for example, selection of sites (Alabama and Montana),

selection of interviewees, and survey questions used. The chapter refers

readers to the Appendix for further methodological details.

4The Last Hope

chapter abstract

Chapter 4 explores the sentiments, held by most interviewees, that America

is an exceptional, even transcendental, country: a place designed and

intended to offer deliverance from the ills that have plagued humanity

throughout history to this very day. America, in a word, represents hope,

both for humanity and for each individual person in the country. The

interviewees evoked pictures of oppressive and destitute places when

describing other countries. America offers reprieve and the possibility of

a better future. The idea of exceptionality was further reinforced by a

belief that, while God is kind and loves everyone equally, he holds America

in a special place in his heart: America is God's country. And with this

there was also an almost tragic sense, described by several, that one has

to believe in America: when all else seems to be a struggle, faith in

country, and in America in particular, is a must.

5The Land of Milk and Honey

chapter abstract

In Chapter 5, many of the people interviewed, despite their own lives'

often difficult trajectories, took pride in America's great wealth and

what, they felt, it means for the country's poor: an abundance of riches

that allows everyone to survive, a feeling that one is being taken care of,

and the conviction that anything is possible in America: despite their own

lives' often difficult trajectories. America, they asserted, despite all

their troubles, is the "land of milk and honey." Many of the interviewees

spoke of the limitations of other countries: run-down, unable to provide

for their people, and oppressive. Everyone still wants to come to the

United States, they said. The country's natural beauty may play a role,

too. Many expressed contentment with their lot. There were differences

between interviewees in Alabama and Montana.

6Freedom

chapter abstract

Chapter 6 discusses how "freedom" was the word that nearly all interviewees

mentioned when accounting for their love of the United States. Questions of

income, social status, or other metrics of personal success were secondary

and often irrelevant. Freedom is at the heart of the American social

contract. Freedom means individual self-determination, both physical and

mental. Those in Montana infused this narrative with considerable

libertarian themes; black interviewees in Alabama tended to point to

progress in racial relations. Only America guarantees the right to bear

arms. This is a matter of self-protection and rebellion against tyranny.

But with guns one can also hunt and feed one's family. Many stressed that

America's freedom was fought for, at great cost, by generations of

Americans. To these we should add more localized patriotic narratives: a

Confederate view of heritage in Alabama and an antigovernment version in

Montana.

7Reconciling Poverty and Patriotism

chapter abstract

Did the interviewees feel a contradiction between their difficult life

situations and love of country? Chapter 7 notes that there was no puzzle in

their minds. They talked about the fairness of outcomes in life, their

sense that new opportunities were about to come along (especially if one is

walking with God), a conviction that everyone is worth the same regardless

of wealth, and, finally, that the United States is really the only country

they know. Taken together, these answers help complete the picture of the

depth and coherence of the patriotism of America's poor. One's precarious

circumstances are no grounds for doubting the greatness of the country.

8An Unshakable Bond

chapter abstract

Chapter 8 summarizes the key findings from the interviews. It emphasizes

the strong, personal, and multifaceted bonds between America's worst-off

and their country. The chapter concludes by reflecting on three broader

themes: inequality and politics in America, the possible evolution and uses

of the patriotism of America's poor (with a specific reference to Donald

Trump's victory in the 2016 presidential election), and the nature of

patriotism across different economic classes in America.