- Broschiertes Buch

- Merkliste

- Auf die Merkliste

- Bewerten Bewerten

- Teilen

- Produkt teilen

- Produkterinnerung

- Produkterinnerung

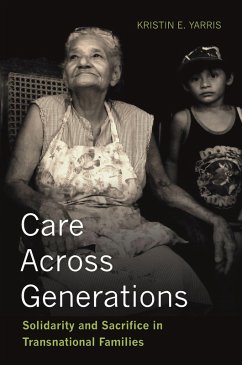

Kristin E. Yarris is Assistant Professor of International Studies at the University of Oregon.

Andere Kunden interessierten sich auch für

![Django Generations Django Generations]() Siv B. LieDjango Generations42,99 €

Siv B. LieDjango Generations42,99 €![Social Media, Technology, and New Generations Social Media, Technology, and New Generations]() Social Media, Technology, and New Generations129,99 €

Social Media, Technology, and New Generations129,99 €![Django Generations Django Generations]() Siv B. LieDjango Generations96,99 €

Siv B. LieDjango Generations96,99 €![Generations of Feeling Generations of Feeling]() Barbara H. Rosenwein (Chicago Loyola University)Generations of Feeling34,99 €

Barbara H. Rosenwein (Chicago Loyola University)Generations of Feeling34,99 €![Showing Social Solidarity with Future Generations Showing Social Solidarity with Future Generations]() Marianne TakleShowing Social Solidarity with Future Generations58,99 €

Marianne TakleShowing Social Solidarity with Future Generations58,99 €![Whatever Happened to Tradition? Whatever Happened to Tradition?]() Tim StanleyWhatever Happened to Tradition?17,99 €

Tim StanleyWhatever Happened to Tradition?17,99 €![Generations Generations]() Twenge, Jean M., PhDGenerations13,99 €

Twenge, Jean M., PhDGenerations13,99 €-

-

-

Kristin E. Yarris is Assistant Professor of International Studies at the University of Oregon.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Produktdetails

- Produktdetails

- Verlag: Stanford University Press

- Seitenzahl: 216

- Erscheinungstermin: 29. August 2017

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 228mm x 151mm x 17mm

- Gewicht: 338g

- ISBN-13: 9781503602885

- ISBN-10: 1503602885

- Artikelnr.: 53016474

- Herstellerkennzeichnung

- Libri GmbH

- Europaallee 1

- 36244 Bad Hersfeld

- gpsr@libri.de

- Verlag: Stanford University Press

- Seitenzahl: 216

- Erscheinungstermin: 29. August 2017

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 228mm x 151mm x 17mm

- Gewicht: 338g

- ISBN-13: 9781503602885

- ISBN-10: 1503602885

- Artikelnr.: 53016474

- Herstellerkennzeichnung

- Libri GmbH

- Europaallee 1

- 36244 Bad Hersfeld

- gpsr@libri.de

Kristin E. Yarris is Assistant Professor of International Studies at the University of Oregon.

Contents and Abstracts

1Tenemos Que Hacerlo: Responsibility and Sacrifice in Grandmother Care

chapter abstract

This chapter reviews patterns of gender and kinship in Nicaraguan families

and shows how gendered inequalities shape grandmothers' assumption of

caregiving following mother migration. The chapter uses ethnographic

examples to demonstrate how grandmothers respond to these gendered

inequalities, negotiating relationships with children's fathers and

managing the legal and social vulnerabilities related to their roles as

intergenerational caregivers. The chapter shows how grandmothers experience

caregiving as both a responsibility-providing everyday care for

children-and as a source of emotional connection, meaning, and motivation.

The chapter documents how grandmothers respond to the prospect of family

reunification-the migration of the children in their care to join mothers

abroad-by drawing on values of solidarity and sacrifice.

2No Se Ajustan: Remittances and Moral Economies of Migration

chapter abstract

This chapter explores the material and affective dimensions of remittances

to illustrate the reconfigurations of care in transnational families and

the related tensions. The chapter shows how a solely material view of the

money migrants send from abroad fails to capture the complex emotional and

affective dimensions of remittances from the perspective of grandmothers

and the children in their care. Just as remittances are a concrete sign

that mothers abroad remain pendiente (responsible) for families in

Nicaragua, they also serve as an unavoidable reminder of mothers' ongoing

absence from everyday family life. In this way, grandmothers' insistence of

remittances that no se ajustan (they do not measure up) indexes a moral

economy of care and migration that sets remittances against the values of

sacrifice and solidarity that grandmothers seek to foster in transnational

family life.

3Pensando Mucho: Transnational Care and Grandmothers' Distress

chapter abstract

This chapter demonstrates the cultural significance of grandmothers' roles

as caregivers in transnational families by exploring their experiences of

embodied, emotional distress. Specifically, the chapter argues that

grandmother caregivers use the expression pensando mucho (thinking too

much) to express the uncertainties and troubles of transnational family

life. The idiom of "thinking too much" indexes the moral ambivalence of

mother migration, which grandmothers understand to be an economic necessity

but which threatens values for unity and solidarity in family life. In this

analysis, by thinking too much grandmothers increase the visibility of

their caregiving by inscribing their significance through a specific set of

somatic symptoms. This communicative aspect of pensando mucho allows

grandmothers to draw attention to their embodied distress, signaling the

disruption of transnational family life while emphasizing the cultural

value of their care.

4Care and Responsibility Across Generations: A Family Migration Portrait

chapter abstract

This chapter presents the story of one Nicaraguan transnational family,

showing how migration's impacts on those who stay behind in migrant-sending

countries are embedded in time and imprinted across generations. In

particular, this close analysis of one family's experience with migration,

taking the grandmother's perspective as the central analytical starting

point, demonstrates how past experiences of migration influence family

members' responses to migration in the present, and how-in turn-present

uncertainties shape hopes and fears for the future. This intergenerational

perspective demonstrates the importance of analyzing migration as both a

temporal and a spatial process, widening our analytical lens on

transnational family life across time and, cumulatively, over generations.

Conclusion: Valuing Care Across Borders and Generations

chapter abstract

Focusing attention on grandmother caregivers' experiences of the

uncertainties of transnational family life calls us to think more broadly

about migration's effects on extended families across national borders, in

host and home countries, and across generations, beyond mothers and

children and into the networks of extended kin who assume essential

caregiving roles in migrant-sending countries like Nicaragua. Grandmothers

in Nicaraguan families assume responsibilities for children of mother

migrants through an informal reconfiguration of caregiving and kinship

obligations, although they lack legal protection and social support. This

chapter reviews the social and political consequences of approaching

transnational migration from an intergenerational perspective, presenting

possible policy responses in migrant-sending and migrant-receiving

countries that would value intergenerational care and support migrants,

caregivers, and children in transnational families.

Introduction: Solidaridad: Nicaraguan Migration and Intergenerational Care

chapter abstract

This chapter presents an overview of the values of solidarity and sacrifice

and their meanings in relation to the reconfigurations of care and kinship

that follow mother migration. The chapter reviews political and economic

dynamics relevant for understanding contemporary Nicaraguan migration. The

chapter situates intergenerational care in transnational families within

recent research on migration and care, including care chains and care

circulations, showing how grandmothers are central actors in global

transformations of care economies. The chapter also reviews current

anthropological theorizing about care, showing how intergenerational care

is a moral practice oriented toward upholding cultural values for family

continuity and for children's everyday well-being in families divided by

borders.

1Tenemos Que Hacerlo: Responsibility and Sacrifice in Grandmother Care

chapter abstract

This chapter reviews patterns of gender and kinship in Nicaraguan families

and shows how gendered inequalities shape grandmothers' assumption of

caregiving following mother migration. The chapter uses ethnographic

examples to demonstrate how grandmothers respond to these gendered

inequalities, negotiating relationships with children's fathers and

managing the legal and social vulnerabilities related to their roles as

intergenerational caregivers. The chapter shows how grandmothers experience

caregiving as both a responsibility-providing everyday care for

children-and as a source of emotional connection, meaning, and motivation.

The chapter documents how grandmothers respond to the prospect of family

reunification-the migration of the children in their care to join mothers

abroad-by drawing on values of solidarity and sacrifice.

2No Se Ajustan: Remittances and Moral Economies of Migration

chapter abstract

This chapter explores the material and affective dimensions of remittances

to illustrate the reconfigurations of care in transnational families and

the related tensions. The chapter shows how a solely material view of the

money migrants send from abroad fails to capture the complex emotional and

affective dimensions of remittances from the perspective of grandmothers

and the children in their care. Just as remittances are a concrete sign

that mothers abroad remain pendiente (responsible) for families in

Nicaragua, they also serve as an unavoidable reminder of mothers' ongoing

absence from everyday family life. In this way, grandmothers' insistence of

remittances that no se ajustan (they do not measure up) indexes a moral

economy of care and migration that sets remittances against the values of

sacrifice and solidarity that grandmothers seek to foster in transnational

family life.

3Pensando Mucho: Transnational Care and Grandmothers' Distress

chapter abstract

This chapter demonstrates the cultural significance of grandmothers' roles

as caregivers in transnational families by exploring their experiences of

embodied, emotional distress. Specifically, the chapter argues that

grandmother caregivers use the expression pensando mucho (thinking too

much) to express the uncertainties and troubles of transnational family

life. The idiom of "thinking too much" indexes the moral ambivalence of

mother migration, which grandmothers understand to be an economic necessity

but which threatens values for unity and solidarity in family life. In this

analysis, by thinking too much grandmothers increase the visibility of

their caregiving by inscribing their significance through a specific set of

somatic symptoms. This communicative aspect of pensando mucho allows

grandmothers to draw attention to their embodied distress, signaling the

disruption of transnational family life while emphasizing the cultural

value of their care.

4Care and Responsibility Across Generations: A Family Migration Portrait

chapter abstract

This chapter presents the story of one Nicaraguan transnational family,

showing how migration's impacts on those who stay behind in migrant-sending

countries are embedded in time and imprinted across generations. In

particular, this close analysis of one family's experience with migration,

taking the grandmother's perspective as the central analytical starting

point, demonstrates how past experiences of migration influence family

members' responses to migration in the present, and how-in turn-present

uncertainties shape hopes and fears for the future. This intergenerational

perspective demonstrates the importance of analyzing migration as both a

temporal and a spatial process, widening our analytical lens on

transnational family life across time and, cumulatively, over generations.

Conclusion: Valuing Care Across Borders and Generations

chapter abstract

Focusing attention on grandmother caregivers' experiences of the

uncertainties of transnational family life calls us to think more broadly

about migration's effects on extended families across national borders, in

host and home countries, and across generations, beyond mothers and

children and into the networks of extended kin who assume essential

caregiving roles in migrant-sending countries like Nicaragua. Grandmothers

in Nicaraguan families assume responsibilities for children of mother

migrants through an informal reconfiguration of caregiving and kinship

obligations, although they lack legal protection and social support. This

chapter reviews the social and political consequences of approaching

transnational migration from an intergenerational perspective, presenting

possible policy responses in migrant-sending and migrant-receiving

countries that would value intergenerational care and support migrants,

caregivers, and children in transnational families.

Introduction: Solidaridad: Nicaraguan Migration and Intergenerational Care

chapter abstract

This chapter presents an overview of the values of solidarity and sacrifice

and their meanings in relation to the reconfigurations of care and kinship

that follow mother migration. The chapter reviews political and economic

dynamics relevant for understanding contemporary Nicaraguan migration. The

chapter situates intergenerational care in transnational families within

recent research on migration and care, including care chains and care

circulations, showing how grandmothers are central actors in global

transformations of care economies. The chapter also reviews current

anthropological theorizing about care, showing how intergenerational care

is a moral practice oriented toward upholding cultural values for family

continuity and for children's everyday well-being in families divided by

borders.

Contents and Abstracts

1Tenemos Que Hacerlo: Responsibility and Sacrifice in Grandmother Care

chapter abstract

This chapter reviews patterns of gender and kinship in Nicaraguan families

and shows how gendered inequalities shape grandmothers' assumption of

caregiving following mother migration. The chapter uses ethnographic

examples to demonstrate how grandmothers respond to these gendered

inequalities, negotiating relationships with children's fathers and

managing the legal and social vulnerabilities related to their roles as

intergenerational caregivers. The chapter shows how grandmothers experience

caregiving as both a responsibility-providing everyday care for

children-and as a source of emotional connection, meaning, and motivation.

The chapter documents how grandmothers respond to the prospect of family

reunification-the migration of the children in their care to join mothers

abroad-by drawing on values of solidarity and sacrifice.

2No Se Ajustan: Remittances and Moral Economies of Migration

chapter abstract

This chapter explores the material and affective dimensions of remittances

to illustrate the reconfigurations of care in transnational families and

the related tensions. The chapter shows how a solely material view of the

money migrants send from abroad fails to capture the complex emotional and

affective dimensions of remittances from the perspective of grandmothers

and the children in their care. Just as remittances are a concrete sign

that mothers abroad remain pendiente (responsible) for families in

Nicaragua, they also serve as an unavoidable reminder of mothers' ongoing

absence from everyday family life. In this way, grandmothers' insistence of

remittances that no se ajustan (they do not measure up) indexes a moral

economy of care and migration that sets remittances against the values of

sacrifice and solidarity that grandmothers seek to foster in transnational

family life.

3Pensando Mucho: Transnational Care and Grandmothers' Distress

chapter abstract

This chapter demonstrates the cultural significance of grandmothers' roles

as caregivers in transnational families by exploring their experiences of

embodied, emotional distress. Specifically, the chapter argues that

grandmother caregivers use the expression pensando mucho (thinking too

much) to express the uncertainties and troubles of transnational family

life. The idiom of "thinking too much" indexes the moral ambivalence of

mother migration, which grandmothers understand to be an economic necessity

but which threatens values for unity and solidarity in family life. In this

analysis, by thinking too much grandmothers increase the visibility of

their caregiving by inscribing their significance through a specific set of

somatic symptoms. This communicative aspect of pensando mucho allows

grandmothers to draw attention to their embodied distress, signaling the

disruption of transnational family life while emphasizing the cultural

value of their care.

4Care and Responsibility Across Generations: A Family Migration Portrait

chapter abstract

This chapter presents the story of one Nicaraguan transnational family,

showing how migration's impacts on those who stay behind in migrant-sending

countries are embedded in time and imprinted across generations. In

particular, this close analysis of one family's experience with migration,

taking the grandmother's perspective as the central analytical starting

point, demonstrates how past experiences of migration influence family

members' responses to migration in the present, and how-in turn-present

uncertainties shape hopes and fears for the future. This intergenerational

perspective demonstrates the importance of analyzing migration as both a

temporal and a spatial process, widening our analytical lens on

transnational family life across time and, cumulatively, over generations.

Conclusion: Valuing Care Across Borders and Generations

chapter abstract

Focusing attention on grandmother caregivers' experiences of the

uncertainties of transnational family life calls us to think more broadly

about migration's effects on extended families across national borders, in

host and home countries, and across generations, beyond mothers and

children and into the networks of extended kin who assume essential

caregiving roles in migrant-sending countries like Nicaragua. Grandmothers

in Nicaraguan families assume responsibilities for children of mother

migrants through an informal reconfiguration of caregiving and kinship

obligations, although they lack legal protection and social support. This

chapter reviews the social and political consequences of approaching

transnational migration from an intergenerational perspective, presenting

possible policy responses in migrant-sending and migrant-receiving

countries that would value intergenerational care and support migrants,

caregivers, and children in transnational families.

Introduction: Solidaridad: Nicaraguan Migration and Intergenerational Care

chapter abstract

This chapter presents an overview of the values of solidarity and sacrifice

and their meanings in relation to the reconfigurations of care and kinship

that follow mother migration. The chapter reviews political and economic

dynamics relevant for understanding contemporary Nicaraguan migration. The

chapter situates intergenerational care in transnational families within

recent research on migration and care, including care chains and care

circulations, showing how grandmothers are central actors in global

transformations of care economies. The chapter also reviews current

anthropological theorizing about care, showing how intergenerational care

is a moral practice oriented toward upholding cultural values for family

continuity and for children's everyday well-being in families divided by

borders.

1Tenemos Que Hacerlo: Responsibility and Sacrifice in Grandmother Care

chapter abstract

This chapter reviews patterns of gender and kinship in Nicaraguan families

and shows how gendered inequalities shape grandmothers' assumption of

caregiving following mother migration. The chapter uses ethnographic

examples to demonstrate how grandmothers respond to these gendered

inequalities, negotiating relationships with children's fathers and

managing the legal and social vulnerabilities related to their roles as

intergenerational caregivers. The chapter shows how grandmothers experience

caregiving as both a responsibility-providing everyday care for

children-and as a source of emotional connection, meaning, and motivation.

The chapter documents how grandmothers respond to the prospect of family

reunification-the migration of the children in their care to join mothers

abroad-by drawing on values of solidarity and sacrifice.

2No Se Ajustan: Remittances and Moral Economies of Migration

chapter abstract

This chapter explores the material and affective dimensions of remittances

to illustrate the reconfigurations of care in transnational families and

the related tensions. The chapter shows how a solely material view of the

money migrants send from abroad fails to capture the complex emotional and

affective dimensions of remittances from the perspective of grandmothers

and the children in their care. Just as remittances are a concrete sign

that mothers abroad remain pendiente (responsible) for families in

Nicaragua, they also serve as an unavoidable reminder of mothers' ongoing

absence from everyday family life. In this way, grandmothers' insistence of

remittances that no se ajustan (they do not measure up) indexes a moral

economy of care and migration that sets remittances against the values of

sacrifice and solidarity that grandmothers seek to foster in transnational

family life.

3Pensando Mucho: Transnational Care and Grandmothers' Distress

chapter abstract

This chapter demonstrates the cultural significance of grandmothers' roles

as caregivers in transnational families by exploring their experiences of

embodied, emotional distress. Specifically, the chapter argues that

grandmother caregivers use the expression pensando mucho (thinking too

much) to express the uncertainties and troubles of transnational family

life. The idiom of "thinking too much" indexes the moral ambivalence of

mother migration, which grandmothers understand to be an economic necessity

but which threatens values for unity and solidarity in family life. In this

analysis, by thinking too much grandmothers increase the visibility of

their caregiving by inscribing their significance through a specific set of

somatic symptoms. This communicative aspect of pensando mucho allows

grandmothers to draw attention to their embodied distress, signaling the

disruption of transnational family life while emphasizing the cultural

value of their care.

4Care and Responsibility Across Generations: A Family Migration Portrait

chapter abstract

This chapter presents the story of one Nicaraguan transnational family,

showing how migration's impacts on those who stay behind in migrant-sending

countries are embedded in time and imprinted across generations. In

particular, this close analysis of one family's experience with migration,

taking the grandmother's perspective as the central analytical starting

point, demonstrates how past experiences of migration influence family

members' responses to migration in the present, and how-in turn-present

uncertainties shape hopes and fears for the future. This intergenerational

perspective demonstrates the importance of analyzing migration as both a

temporal and a spatial process, widening our analytical lens on

transnational family life across time and, cumulatively, over generations.

Conclusion: Valuing Care Across Borders and Generations

chapter abstract

Focusing attention on grandmother caregivers' experiences of the

uncertainties of transnational family life calls us to think more broadly

about migration's effects on extended families across national borders, in

host and home countries, and across generations, beyond mothers and

children and into the networks of extended kin who assume essential

caregiving roles in migrant-sending countries like Nicaragua. Grandmothers

in Nicaraguan families assume responsibilities for children of mother

migrants through an informal reconfiguration of caregiving and kinship

obligations, although they lack legal protection and social support. This

chapter reviews the social and political consequences of approaching

transnational migration from an intergenerational perspective, presenting

possible policy responses in migrant-sending and migrant-receiving

countries that would value intergenerational care and support migrants,

caregivers, and children in transnational families.

Introduction: Solidaridad: Nicaraguan Migration and Intergenerational Care

chapter abstract

This chapter presents an overview of the values of solidarity and sacrifice

and their meanings in relation to the reconfigurations of care and kinship

that follow mother migration. The chapter reviews political and economic

dynamics relevant for understanding contemporary Nicaraguan migration. The

chapter situates intergenerational care in transnational families within

recent research on migration and care, including care chains and care

circulations, showing how grandmothers are central actors in global

transformations of care economies. The chapter also reviews current

anthropological theorizing about care, showing how intergenerational care

is a moral practice oriented toward upholding cultural values for family

continuity and for children's everyday well-being in families divided by

borders.