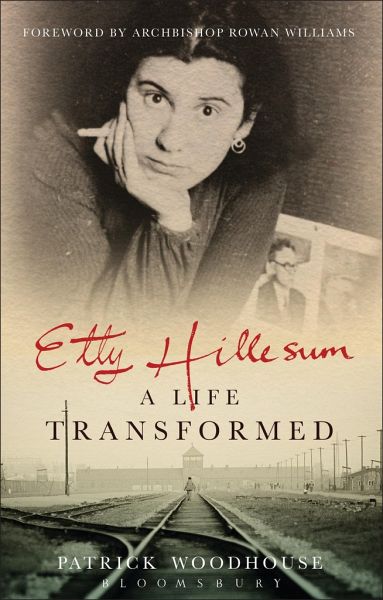

Etty Hillesum: A Life Transformed

PAYBACK Punkte

12 °P sammeln!

On 8 March 1941, a 27-year-old Jewish Dutch student living in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam made the first entry in a diary that was to become one of the most remarkable documents to emerge from the Nazi Holocaust. Over the course of the next two and a half years, an insecure, chaotic and troubled young woman was transformed into someone who inspired those with whom she shared the suffering of the transit camp at Westerbork and with whom she eventually perished at Auschwitz. Through her diary and letters, she continues to inspire those whose lives she has touched since. She was an extraordinarily al...

On 8 March 1941, a 27-year-old Jewish Dutch student living in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam made the first entry in a diary that was to become one of the most remarkable documents to emerge from the Nazi Holocaust. Over the course of the next two and a half years, an insecure, chaotic and troubled young woman was transformed into someone who inspired those with whom she shared the suffering of the transit camp at Westerbork and with whom she eventually perished at Auschwitz. Through her diary and letters, she continues to inspire those whose lives she has touched since. She was an extraordinarily alive and vivid young woman who shaped and lived a spirituality of hope in the darkest period of the twentieth century. This book explores Etty Hillesum's life and writings, seeking to understand what it was about her that was so remarkable, how her journey developed, how her spirituality was shaped, and what her profound reflections on the roots of violence and the nature of evil can teach us today.