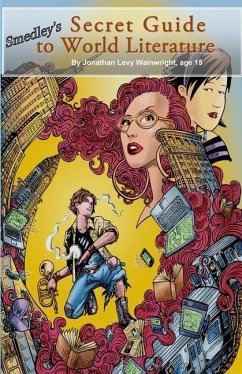

Askold Melnyczuk

Excerpt from Smedley's Secret Guide to World Literature

17,99 €

inkl. MwSt.

Versandfertig in über 4 Wochen

Askold Melnyczuk

Excerpt from Smedley's Secret Guide to World Literature

- Broschiertes Buch

- Merkliste

- Auf die Merkliste

- Bewerten Bewerten

- Teilen

- Produkt teilen

- Produkterinnerung

- Produkterinnerung

Why is everyone angry with Jonathan? Suspended from school a week before Memorial Day, the savvy and cyber-sexed fifteen-year old is charged by his poet-father to write a history of literature in the age of Twitter. Jonathan absconds to Manhattan to care for his high-living godfather, who recently had a s

Andere Kunden interessierten sich auch für

![Orphan Train Orphan Train]() Christina Baker KlineOrphan Train22,99 €

Christina Baker KlineOrphan Train22,99 €![EXCERPT Magazine - No. 2 EXCERPT Magazine - No. 2]() EXCERPT Magazine - No. 214,99 €

EXCERPT Magazine - No. 214,99 €![EXCERPT Magazine - No. 1 EXCERPT Magazine - No. 1]() EXCERPT Magazine - No. 114,99 €

EXCERPT Magazine - No. 114,99 €![The Poisonwood Bible The Poisonwood Bible]() Barbara KingsolverThe Poisonwood Bible21,99 €

Barbara KingsolverThe Poisonwood Bible21,99 €![Back to the World Back to the World]() Joe CampoloBack to the World15,99 €

Joe CampoloBack to the World15,99 €![The Tusk That Did the Damage The Tusk That Did the Damage]() Tania JamesThe Tusk That Did the Damage16,99 €

Tania JamesThe Tusk That Did the Damage16,99 €![Glitched Away: To The World of Cyrodiil Glitched Away: To The World of Cyrodiil]() Ronald KnipferGlitched Away: To The World of Cyrodiil16,99 €

Ronald KnipferGlitched Away: To The World of Cyrodiil16,99 €-

-

Why is everyone angry with Jonathan? Suspended from school a week before Memorial Day, the savvy and cyber-sexed fifteen-year old is charged by his poet-father to write a history of literature in the age of Twitter. Jonathan absconds to Manhattan to care for his high-living godfather, who recently had a s

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Produktdetails

- Produktdetails

- Verlag: Authors' Tranquility Press

- Seitenzahl: 254

- Erscheinungstermin: 16. April 2016

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 216mm x 140mm x 18mm

- Gewicht: 340g

- ISBN-13: 9780997024814

- ISBN-10: 099702481X

- Artikelnr.: 44609728

- Verlag: Authors' Tranquility Press

- Seitenzahl: 254

- Erscheinungstermin: 16. April 2016

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 216mm x 140mm x 18mm

- Gewicht: 340g

- ISBN-13: 9780997024814

- ISBN-10: 099702481X

- Artikelnr.: 44609728

This book is so different from your first three novels. I see each book as an experiment. It begins in a need, an impulse, an itch that's more physical than mental--a kind of pressure lodged somewhere in my body which the act of writing alone is able to relieve. Anyway, I never know what voice is going to whisper in my ear, or why, or what it wants. My task, at least initially, when starting a book is to attend, to be present, to record as much as it's willing to give. Some days it's generous, others nearly mute. The "bad" days (and they're not always actually "bad") are when my conscious mind kicks in and I start thinking about structure, and start the nearly endless process of tinkering with sentences. Where did the idea for this come from? Jonathan's voice first arose just as I was entering the heavy-lifting phase of eldercare with my parents. It helped me through many a rough day in the nursing homes, hospitals, and rehab centers which have become such a regular part of my routine. I remember feeling kind of overwhelmed, sitting in the Cambridge Public Library, flipping through Aubrey's Brief Lives. It's a series of short, gossipy biographical sketches, written in the 17th century, about various acquaintances and contemporaries of Aubrey's, including people like Milton and the poet Lovelace. While reading, I "heard" a voice making all kinds of wisecracks, prying between the lines of what Aubrey wrote and what he actually meant to communicate. The voice made me laugh, something I really needed at the time. Once I had tuned into that voice, I kept wanting to know what it might say about X or Y....It was the narrator's sassiness that appealed to me. His shoot-from-the-hip attitude helped keep up my spirits while surrounded by the responsibilities and inevitable sadnesses associated with the aging of loved ones. As I was writing, the Occupy Movement was unfolding here, with many echoes around the world. A new generation of young people was beginning to take part in the remaking of our planet--a thing our earth sorely needs. I was thrilled. Jonathan, though far from the front lines, became a spiritual fellow-traveler with his peers worldwide. That's why the book is dedicated "to the rebel soul in everyone." What are some of the challenges that come with writing from the POV of a fifteen year old? He's not just any fifteen year old! He's a scion of privilege, who has grown up in one of the most exclusive and elitist enclaves in the world. His father is a WASP; his mother is a secular Jew. In short, he's a lot farther from me than many readers will understand. In many ways, he's farther from me than Mme X, a middle-aged British Jew who lived through the London blitz, whose voice I assumed in my last novel, The House of Widows. If Jonathan's world was completely foreign to me, his hometown of Cambridge, where I arrived in 1976, was once a good place in which to be poor. I used to bounce checks regularly at the Evergood Market, which I learned recently is owned by the family of Peter Segal, who does that show Wait Wait Don't Tell Me on the radio. I'd walk in and find my check tacked to a bulletin board next to the cash register for all to see. Yet the owners always let me redeem it, and continued taking checks from me even though--and I'm not exaggerating--for a time, every other one bounced.... So, for me to write in the voice of a child who'd grown up inside all this privilege was in a way my attempt to find out if I had put my prejudices behind me. Could I see the world through his eyes? Could I empathize with him, despite his privileges? Whether or not I've succeeded is of course for readers to decide for themselves. For all that, in a funny way this feels like my most personal book. Aside from my delight at inhabiting the skin of the randy fifteen year old, there were things I felt able to say...or that I heard myself saying, which I'd never imagined getting into. It helps that Jonathan's a rebel, and not a snob. When his professor-father tells him to write a history of literature in the age of Twitter, Smedley responds by focusing on a quite unusual list of writers. I've heard that some people have been puzzled by the writers Jonathan picks for his essay. Certainly they're not the usual suspects. It would have been easy, and tempting, as well as perhaps more commercially savvy, to pick the familiar and the enshrined: Woolf, Borges, Calvino, Sebald, etc. These are the "cool" international writers properly beloved by readers. But they are just part of the story. There are many others equally worthy of our attention. You might call part of the book's secret project both an attempt at rethinking our received ideas about the classics, as well as a bit of fun had with the whole notion of a conclusive list of "the great books." The hierarchies which haunt so many aspects of our contemporary civilization, always expressed in numerical terms--top ten lists, our fifty richest people, our hundred best restaurants, etc--are rarely, if ever, definitive. But the list is far from arbitrary--and was, in earlier drafts, a lot longer. In fact, most of the writers Jonathan selects were rebels of one sort or another, from the 17th century courtier Richard Lovelace, who wrote what's perhaps the greatest prison poem in the language ("Stone walls do not a prison make...) to Agnes Smedly, born dirt-poor in poor in Osgood, Missouri, to a coal-miner father, who began her career as a school teacher in rural Colorado and wound up as an international correspondent writing for papers in Germany, France, China, India and the US. She fell in love with an Indian spy, taught Mao to dance, lived for years at Yaddo, a writer's colony in upstate New York, but died broke in London, and is buried in Beijing. I think of her as a kind of early version of Amy Goodman/Terry Gross hybridized with Martha Gellhorn. Like most kids his age, Jonathan is totally immersed in the virtual world. Yes, he spends a lot of his time online. But in the last part of the book, he leaves his iPad at home, and then he loses his cell phone. When he finally faces Beyah, who he believes is the object of his desire, he's essentially naked. It's just one human being facing another--no texting, no screens. Though he's grown up in a world of icons and endless visual stimulation, he gradually discovers the singular power of presence, print, and, even, inwardness. Despite Jonathan's protestations, this does indeed seem like a coming of age story. Yes and no. I kind of agree with Jonathan when he says that no one comes of age anymore. Okay, most people do settle on a self and stick with it. At the same time, we are porous beings and invaders are boring into us from all sides. Despite our privileges and first-world advantages--or because of them--we're incredibly vulnerable to the temptations of consumerism, among other things. At the same time, I have high hopes that Jonathan, having felt the consequences of his family's instability, will move through life a little more aware of the ways in which our actions ripple out and affect others.