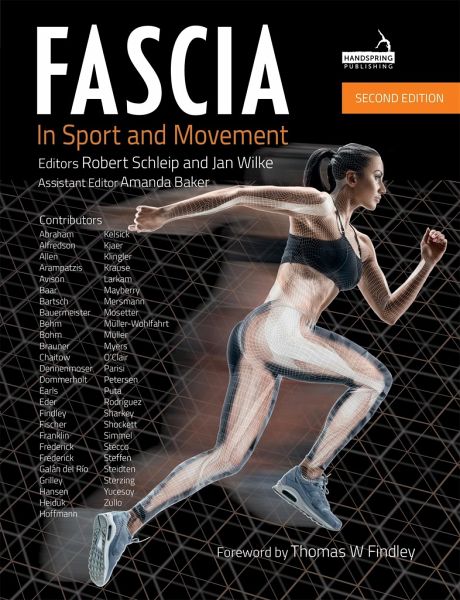

Fascia in Sport and Movement, Second edition

Versandkostenfrei!

Versandfertig in 2-4 Wochen

103,99 €

inkl. MwSt.

PAYBACK Punkte

52 °P sammeln!

Fascia in Sport and Movement, Second edition is a multi-author book with contributions from 51 leading teachers and practitioners across the entire spectrum of bodywork and movement professions. It provides professionals from all bodywork and movement specialisms with the most up-to-date information they need for success in teaching, training, coaching, strengthening, tackling injury, reducing pain, and improving mobility. The new edition has 21 new chapters, and chapters from the first edition have been updated with new research. This book is an essential resource for all bodywork professiona...

Fascia in Sport and Movement, Second edition is a multi-author book with contributions from 51 leading teachers and practitioners across the entire spectrum of bodywork and movement professions. It provides professionals from all bodywork and movement specialisms with the most up-to-date information they need for success in teaching, training, coaching, strengthening, tackling injury, reducing pain, and improving mobility. The new edition has 21 new chapters, and chapters from the first edition have been updated with new research. This book is an essential resource for all bodywork professionals - sports coaches, fitness trainers, yoga teachers, Pilates instructors, dance teachers and manual therapists. It explains and demonstrates how an understanding of the structure and function of fascia can inform and improve your clinical practice. The book's unique strength lies in the breadth of its coverage, the expertise of its authorship and the currency of its research and practice base.