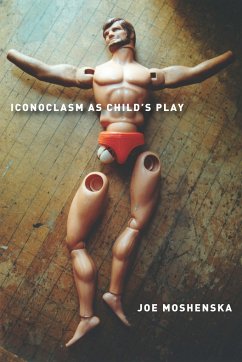

Joe Moshenska

Iconoclasm as Child's Play

Joe Moshenska

Iconoclasm as Child's Play

- Gebundenes Buch

- Merkliste

- Auf die Merkliste

- Bewerten Bewerten

- Teilen

- Produkt teilen

- Produkterinnerung

- Produkterinnerung

Taking its impetus from remarkable fact that holy things were given to children as toys in the early modern period as a way of destroying their power, this book rethinks the meaning of both iconoclasm and child's play then and now.

Andere Kunden interessierten sich auch für

![Child's Play Child's Play]() Danielle SteelChild's Play12,99 €

Danielle SteelChild's Play12,99 €![The Child's World, Third Edition The Child's World, Third Edition]() The Child's World, Third Edition46,99 €

The Child's World, Third Edition46,99 €![Parenting is (Not) Child's Play Parenting is (Not) Child's Play]() Orit Josefi WisemanParenting is (Not) Child's Play14,99 €

Orit Josefi WisemanParenting is (Not) Child's Play14,99 €![A Child's Day A Child's Day]() Killian Mullan (Aston University)A Child's Day42,99 €

Killian Mullan (Aston University)A Child's Day42,99 €![Early Education Curriculum: A Child's Connection to the World Early Education Curriculum: A Child's Connection to the World]() Nancy Beaver (a campus of Dallas Co Retired from Eastfield CollegeEarly Education Curriculum: A Child's Connection to the World95,99 €

Nancy Beaver (a campus of Dallas Co Retired from Eastfield CollegeEarly Education Curriculum: A Child's Connection to the World95,99 €![Child's Play Child's Play]() Ramiro Jose PeraltaChild's Play10,99 €

Ramiro Jose PeraltaChild's Play10,99 €![Honey for a Child's Heart Honey for a Child's Heart]() Gladys HuntHoney for a Child's Heart18,99 €

Gladys HuntHoney for a Child's Heart18,99 €-

-

-

Taking its impetus from remarkable fact that holy things were given to children as toys in the early modern period as a way of destroying their power, this book rethinks the meaning of both iconoclasm and child's play then and now.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Produktdetails

- Produktdetails

- Verlag: Stanford University Press

- Seitenzahl: 272

- Erscheinungstermin: 16. April 2019

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 237mm x 162mm x 25mm

- Gewicht: 570g

- ISBN-13: 9780804798501

- ISBN-10: 0804798508

- Artikelnr.: 53544160

- Herstellerkennzeichnung

- Libri GmbH

- Europaallee 1

- 36244 Bad Hersfeld

- 06621 890

- Verlag: Stanford University Press

- Seitenzahl: 272

- Erscheinungstermin: 16. April 2019

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 237mm x 162mm x 25mm

- Gewicht: 570g

- ISBN-13: 9780804798501

- ISBN-10: 0804798508

- Artikelnr.: 53544160

- Herstellerkennzeichnung

- Libri GmbH

- Europaallee 1

- 36244 Bad Hersfeld

- 06621 890

Joe Moshenska is Associate Professor of English, University of Oxford, and Tutorial Fellow of University College.

Contents and Abstracts

Preface: Preface

chapter abstract

The preface begins with a sermon by Roger Edgeworth, delivered in the West

of England in the 1530s, that describes children playing with objects

removed from monasteries. The children are interrupted by their parents,

who insist that these objects be denounced as "idols." Drawing on

discussions from art history and political theory, it suggests that this

scene is emblematic of the way in which the closed world of child's play

seems both to demand and to resist interpretation. It distinguishes the

delicate interpretative balance of the scene from some more recent attempts

to see play either as entirely open and free or as entirely closed and

predetermined, and sketches out the overall trajectory of the book.

Introduction: Introduction

chapter abstract

The introduction traces the wider historical and theoretical narratives in

which iconoclasm and child's play have played prominent-but typically

opposed-roles. It begins with Baudelaire's association of parents who deny

toys to their children with Protestantism, and shows that this is

symptomatic of a widely postulated opposition between play and the

Reformation, linked to the identification of violently iconoclastic

disenchantment as the essence of modernity. It then explores the roles that

iconoclasm and play assumed in the emergence of modern aesthetics from

Schiller to Gadamer, and the prominence of toys in modern accounts of

materiality. These discussions set up the larger narratives of iconoclasm

and play against which the texture of iconoclastic child's play itself is

tested in the chapters that follow.

1Trifle

chapter abstract

This chapter begins with lists compiled in Lincolnshire in the 1550s. These

lists show that objects including pyxes-containers for the Eucharist-were

given to children as playthings. The chapter links this practice to the

widespread discourse that sought to demean traditional religion as a mere

trifling with inane and worthless things, but it argues that the practice

of iconoclastic child's play differs from this polemic in that the object

actually lingers as a potential locus for newly emerging meanings. This

possibility is linked to the wider complexities surrounding the status of

trifles and inanities in the history of Christian thought and its

consistent inversions of value, as well as to the self-reflexive

interrogation of the status of trifles in the writings of Thomas More.

2Doll

chapter abstract

This chapter opens with a father in Cologne in the 1590s who snapped the

arms from a crucifix and gave it to his children as a toy. Returning to the

sermon by Edgeworth discussed in the preface, the chapter considers this

broken object as what Edgeworth calls an "idoll"-a hybridization of doll

and idoll. This possibility is linked to the wider presence of "holy dolls"

in medieval Christianity, but ultimately the doll is explored not as a

stable and readily identifiable category but as a way of conceiving of

ambiguous objects that may be more or less human at different moments and

subjected alternatingly to violence and care. The implications of this

possibility are explored in relation to a medieval Christ child, a broken

crucifix, and a contemporary representation of a shattered doll.

3Puppet

chapter abstract

This chapter opens with a movable image of a dove, representing the Holy

Spirit, that was made into a plaything in sixteenth century Germany. It

relates this specific object to a wider range of articulated and jointed

figures involved in late medieval piety that were often attacked as empty

puppets by reformers. It uses these objects to think not about puppets per

se but rather about the jointedness or constitutive brokenness of holy

things more broadly, particularly relics poised between the sacred and the

disgusting. These objects are related to the unstable place of playfulness

and the material in Erasmus's writings, and to the wider place of creative

breaking and the disgusting in modern art.

4Fetish

chapter abstract

This chapter opens with an ambiguous set of objects collected by a Dutch

woman named Margrieta van Varick and described as "Indian Babies," possibly

brought with her from the Dutch East Indies to New England, and relates

them to the practice of iconoclastic child's play in Malaysia. It

repositions iconoclastic child's play in a fraught colonial context and

asks how the play of other cultures is to be interpreted. Beginning with

ethnographic and psychoanalytic discussions of child's play by

Lévi-Strauss, Winnicott, and others, it then moves to consider the category

of the fetish as one that has long been intertwined with the status of

children and their playing. It uses the contested status of this

category-as an object both replete with, and devoid of, meaning-to

reconsider the fetish as plaything both in sixteenth-century Guinea and in

Adorno's writing on artworks and children's games.

5Play

chapter abstract

This chapter opens with a set of medieval wooden statues in Audley End

House in Essex that survived in part because they spent a period being used

by children as toys. It considers the uneven trajectories through which

these objects have passed-existing at different points as holy things,

playthings, and art-things-to consider the wider temporal narratives into

which play (and especially the playing of children) is often folded. It

considers the way in which educative and habituating schemes from Plato to

Renaissance figures such as Thomas Elyot and Montaigne involve the

interpretation of play as a linear process of habituation, but it argues

that these narratives involve a defensive simplification of the way in

which play can in fact unfold in and through time, an attempt to limit and

tame its meanings.

6Mask

chapter abstract

This chapter begins with a wooden doll from the seventeenth century that is

juxtaposed with the statues from Audley End considered in the previous

chapter on the basis of their equally fixed, impassive visages. This

feature is used to consider the way in which children, especially when at

play, have been seen as troublingly masked, inscrutable, alien beings. It

discusses accounts from the sixteenth century, notably John Harington's,

that recognize in play periods of vacant, blank, neutral time. It then

proceeds to an extended reading of Bruegel's painting Children's Games, and

especially a consideration of the reading of this work by the Nazi art

historian Hans Sedlmayr. This painting, and Sedlmayr's remarkable and

deeply disquieting account, are seen as encapsulating the ways in which

child's play's resistance to interpretation can provoke fear and horror-a

possibility linked to the periodic association of children with witchcraft

and demonic possession.

Conclusion: Toy

chapter abstract

The conclusion returns to the larger narratives into which play has often

been folded in order to reconsider them in relation to the complexities of

iconoclastic child's play. It suggests that neat temporalities in which

play and seriousness contrast and alternate with one another need to be

replaced with trajectories that have room for sudden alteration and

reversal. Drawing in part from the writings of Hans Blumenberg, Bruno

Latour, Michel Serres, Siegfried Kracauer, and Igor Kopytoff, it suggests

that we think of objects (including artworks) in terms of their "toy

potential"-the perennial possibility that an object might both come to be,

and cease to be, a plaything. The implications of this possibility are

illustrated via a reading of an episode from Spenser's Faerie Queene in

which a malevolent allegorical dragon is startlingly transformed into a

child's plaything.

Preface: Preface

chapter abstract

The preface begins with a sermon by Roger Edgeworth, delivered in the West

of England in the 1530s, that describes children playing with objects

removed from monasteries. The children are interrupted by their parents,

who insist that these objects be denounced as "idols." Drawing on

discussions from art history and political theory, it suggests that this

scene is emblematic of the way in which the closed world of child's play

seems both to demand and to resist interpretation. It distinguishes the

delicate interpretative balance of the scene from some more recent attempts

to see play either as entirely open and free or as entirely closed and

predetermined, and sketches out the overall trajectory of the book.

Introduction: Introduction

chapter abstract

The introduction traces the wider historical and theoretical narratives in

which iconoclasm and child's play have played prominent-but typically

opposed-roles. It begins with Baudelaire's association of parents who deny

toys to their children with Protestantism, and shows that this is

symptomatic of a widely postulated opposition between play and the

Reformation, linked to the identification of violently iconoclastic

disenchantment as the essence of modernity. It then explores the roles that

iconoclasm and play assumed in the emergence of modern aesthetics from

Schiller to Gadamer, and the prominence of toys in modern accounts of

materiality. These discussions set up the larger narratives of iconoclasm

and play against which the texture of iconoclastic child's play itself is

tested in the chapters that follow.

1Trifle

chapter abstract

This chapter begins with lists compiled in Lincolnshire in the 1550s. These

lists show that objects including pyxes-containers for the Eucharist-were

given to children as playthings. The chapter links this practice to the

widespread discourse that sought to demean traditional religion as a mere

trifling with inane and worthless things, but it argues that the practice

of iconoclastic child's play differs from this polemic in that the object

actually lingers as a potential locus for newly emerging meanings. This

possibility is linked to the wider complexities surrounding the status of

trifles and inanities in the history of Christian thought and its

consistent inversions of value, as well as to the self-reflexive

interrogation of the status of trifles in the writings of Thomas More.

2Doll

chapter abstract

This chapter opens with a father in Cologne in the 1590s who snapped the

arms from a crucifix and gave it to his children as a toy. Returning to the

sermon by Edgeworth discussed in the preface, the chapter considers this

broken object as what Edgeworth calls an "idoll"-a hybridization of doll

and idoll. This possibility is linked to the wider presence of "holy dolls"

in medieval Christianity, but ultimately the doll is explored not as a

stable and readily identifiable category but as a way of conceiving of

ambiguous objects that may be more or less human at different moments and

subjected alternatingly to violence and care. The implications of this

possibility are explored in relation to a medieval Christ child, a broken

crucifix, and a contemporary representation of a shattered doll.

3Puppet

chapter abstract

This chapter opens with a movable image of a dove, representing the Holy

Spirit, that was made into a plaything in sixteenth century Germany. It

relates this specific object to a wider range of articulated and jointed

figures involved in late medieval piety that were often attacked as empty

puppets by reformers. It uses these objects to think not about puppets per

se but rather about the jointedness or constitutive brokenness of holy

things more broadly, particularly relics poised between the sacred and the

disgusting. These objects are related to the unstable place of playfulness

and the material in Erasmus's writings, and to the wider place of creative

breaking and the disgusting in modern art.

4Fetish

chapter abstract

This chapter opens with an ambiguous set of objects collected by a Dutch

woman named Margrieta van Varick and described as "Indian Babies," possibly

brought with her from the Dutch East Indies to New England, and relates

them to the practice of iconoclastic child's play in Malaysia. It

repositions iconoclastic child's play in a fraught colonial context and

asks how the play of other cultures is to be interpreted. Beginning with

ethnographic and psychoanalytic discussions of child's play by

Lévi-Strauss, Winnicott, and others, it then moves to consider the category

of the fetish as one that has long been intertwined with the status of

children and their playing. It uses the contested status of this

category-as an object both replete with, and devoid of, meaning-to

reconsider the fetish as plaything both in sixteenth-century Guinea and in

Adorno's writing on artworks and children's games.

5Play

chapter abstract

This chapter opens with a set of medieval wooden statues in Audley End

House in Essex that survived in part because they spent a period being used

by children as toys. It considers the uneven trajectories through which

these objects have passed-existing at different points as holy things,

playthings, and art-things-to consider the wider temporal narratives into

which play (and especially the playing of children) is often folded. It

considers the way in which educative and habituating schemes from Plato to

Renaissance figures such as Thomas Elyot and Montaigne involve the

interpretation of play as a linear process of habituation, but it argues

that these narratives involve a defensive simplification of the way in

which play can in fact unfold in and through time, an attempt to limit and

tame its meanings.

6Mask

chapter abstract

This chapter begins with a wooden doll from the seventeenth century that is

juxtaposed with the statues from Audley End considered in the previous

chapter on the basis of their equally fixed, impassive visages. This

feature is used to consider the way in which children, especially when at

play, have been seen as troublingly masked, inscrutable, alien beings. It

discusses accounts from the sixteenth century, notably John Harington's,

that recognize in play periods of vacant, blank, neutral time. It then

proceeds to an extended reading of Bruegel's painting Children's Games, and

especially a consideration of the reading of this work by the Nazi art

historian Hans Sedlmayr. This painting, and Sedlmayr's remarkable and

deeply disquieting account, are seen as encapsulating the ways in which

child's play's resistance to interpretation can provoke fear and horror-a

possibility linked to the periodic association of children with witchcraft

and demonic possession.

Conclusion: Toy

chapter abstract

The conclusion returns to the larger narratives into which play has often

been folded in order to reconsider them in relation to the complexities of

iconoclastic child's play. It suggests that neat temporalities in which

play and seriousness contrast and alternate with one another need to be

replaced with trajectories that have room for sudden alteration and

reversal. Drawing in part from the writings of Hans Blumenberg, Bruno

Latour, Michel Serres, Siegfried Kracauer, and Igor Kopytoff, it suggests

that we think of objects (including artworks) in terms of their "toy

potential"-the perennial possibility that an object might both come to be,

and cease to be, a plaything. The implications of this possibility are

illustrated via a reading of an episode from Spenser's Faerie Queene in

which a malevolent allegorical dragon is startlingly transformed into a

child's plaything.

Contents and Abstracts

Preface: Preface

chapter abstract

The preface begins with a sermon by Roger Edgeworth, delivered in the West

of England in the 1530s, that describes children playing with objects

removed from monasteries. The children are interrupted by their parents,

who insist that these objects be denounced as "idols." Drawing on

discussions from art history and political theory, it suggests that this

scene is emblematic of the way in which the closed world of child's play

seems both to demand and to resist interpretation. It distinguishes the

delicate interpretative balance of the scene from some more recent attempts

to see play either as entirely open and free or as entirely closed and

predetermined, and sketches out the overall trajectory of the book.

Introduction: Introduction

chapter abstract

The introduction traces the wider historical and theoretical narratives in

which iconoclasm and child's play have played prominent-but typically

opposed-roles. It begins with Baudelaire's association of parents who deny

toys to their children with Protestantism, and shows that this is

symptomatic of a widely postulated opposition between play and the

Reformation, linked to the identification of violently iconoclastic

disenchantment as the essence of modernity. It then explores the roles that

iconoclasm and play assumed in the emergence of modern aesthetics from

Schiller to Gadamer, and the prominence of toys in modern accounts of

materiality. These discussions set up the larger narratives of iconoclasm

and play against which the texture of iconoclastic child's play itself is

tested in the chapters that follow.

1Trifle

chapter abstract

This chapter begins with lists compiled in Lincolnshire in the 1550s. These

lists show that objects including pyxes-containers for the Eucharist-were

given to children as playthings. The chapter links this practice to the

widespread discourse that sought to demean traditional religion as a mere

trifling with inane and worthless things, but it argues that the practice

of iconoclastic child's play differs from this polemic in that the object

actually lingers as a potential locus for newly emerging meanings. This

possibility is linked to the wider complexities surrounding the status of

trifles and inanities in the history of Christian thought and its

consistent inversions of value, as well as to the self-reflexive

interrogation of the status of trifles in the writings of Thomas More.

2Doll

chapter abstract

This chapter opens with a father in Cologne in the 1590s who snapped the

arms from a crucifix and gave it to his children as a toy. Returning to the

sermon by Edgeworth discussed in the preface, the chapter considers this

broken object as what Edgeworth calls an "idoll"-a hybridization of doll

and idoll. This possibility is linked to the wider presence of "holy dolls"

in medieval Christianity, but ultimately the doll is explored not as a

stable and readily identifiable category but as a way of conceiving of

ambiguous objects that may be more or less human at different moments and

subjected alternatingly to violence and care. The implications of this

possibility are explored in relation to a medieval Christ child, a broken

crucifix, and a contemporary representation of a shattered doll.

3Puppet

chapter abstract

This chapter opens with a movable image of a dove, representing the Holy

Spirit, that was made into a plaything in sixteenth century Germany. It

relates this specific object to a wider range of articulated and jointed

figures involved in late medieval piety that were often attacked as empty

puppets by reformers. It uses these objects to think not about puppets per

se but rather about the jointedness or constitutive brokenness of holy

things more broadly, particularly relics poised between the sacred and the

disgusting. These objects are related to the unstable place of playfulness

and the material in Erasmus's writings, and to the wider place of creative

breaking and the disgusting in modern art.

4Fetish

chapter abstract

This chapter opens with an ambiguous set of objects collected by a Dutch

woman named Margrieta van Varick and described as "Indian Babies," possibly

brought with her from the Dutch East Indies to New England, and relates

them to the practice of iconoclastic child's play in Malaysia. It

repositions iconoclastic child's play in a fraught colonial context and

asks how the play of other cultures is to be interpreted. Beginning with

ethnographic and psychoanalytic discussions of child's play by

Lévi-Strauss, Winnicott, and others, it then moves to consider the category

of the fetish as one that has long been intertwined with the status of

children and their playing. It uses the contested status of this

category-as an object both replete with, and devoid of, meaning-to

reconsider the fetish as plaything both in sixteenth-century Guinea and in

Adorno's writing on artworks and children's games.

5Play

chapter abstract

This chapter opens with a set of medieval wooden statues in Audley End

House in Essex that survived in part because they spent a period being used

by children as toys. It considers the uneven trajectories through which

these objects have passed-existing at different points as holy things,

playthings, and art-things-to consider the wider temporal narratives into

which play (and especially the playing of children) is often folded. It

considers the way in which educative and habituating schemes from Plato to

Renaissance figures such as Thomas Elyot and Montaigne involve the

interpretation of play as a linear process of habituation, but it argues

that these narratives involve a defensive simplification of the way in

which play can in fact unfold in and through time, an attempt to limit and

tame its meanings.

6Mask

chapter abstract

This chapter begins with a wooden doll from the seventeenth century that is

juxtaposed with the statues from Audley End considered in the previous

chapter on the basis of their equally fixed, impassive visages. This

feature is used to consider the way in which children, especially when at

play, have been seen as troublingly masked, inscrutable, alien beings. It

discusses accounts from the sixteenth century, notably John Harington's,

that recognize in play periods of vacant, blank, neutral time. It then

proceeds to an extended reading of Bruegel's painting Children's Games, and

especially a consideration of the reading of this work by the Nazi art

historian Hans Sedlmayr. This painting, and Sedlmayr's remarkable and

deeply disquieting account, are seen as encapsulating the ways in which

child's play's resistance to interpretation can provoke fear and horror-a

possibility linked to the periodic association of children with witchcraft

and demonic possession.

Conclusion: Toy

chapter abstract

The conclusion returns to the larger narratives into which play has often

been folded in order to reconsider them in relation to the complexities of

iconoclastic child's play. It suggests that neat temporalities in which

play and seriousness contrast and alternate with one another need to be

replaced with trajectories that have room for sudden alteration and

reversal. Drawing in part from the writings of Hans Blumenberg, Bruno

Latour, Michel Serres, Siegfried Kracauer, and Igor Kopytoff, it suggests

that we think of objects (including artworks) in terms of their "toy

potential"-the perennial possibility that an object might both come to be,

and cease to be, a plaything. The implications of this possibility are

illustrated via a reading of an episode from Spenser's Faerie Queene in

which a malevolent allegorical dragon is startlingly transformed into a

child's plaything.

Preface: Preface

chapter abstract

The preface begins with a sermon by Roger Edgeworth, delivered in the West

of England in the 1530s, that describes children playing with objects

removed from monasteries. The children are interrupted by their parents,

who insist that these objects be denounced as "idols." Drawing on

discussions from art history and political theory, it suggests that this

scene is emblematic of the way in which the closed world of child's play

seems both to demand and to resist interpretation. It distinguishes the

delicate interpretative balance of the scene from some more recent attempts

to see play either as entirely open and free or as entirely closed and

predetermined, and sketches out the overall trajectory of the book.

Introduction: Introduction

chapter abstract

The introduction traces the wider historical and theoretical narratives in

which iconoclasm and child's play have played prominent-but typically

opposed-roles. It begins with Baudelaire's association of parents who deny

toys to their children with Protestantism, and shows that this is

symptomatic of a widely postulated opposition between play and the

Reformation, linked to the identification of violently iconoclastic

disenchantment as the essence of modernity. It then explores the roles that

iconoclasm and play assumed in the emergence of modern aesthetics from

Schiller to Gadamer, and the prominence of toys in modern accounts of

materiality. These discussions set up the larger narratives of iconoclasm

and play against which the texture of iconoclastic child's play itself is

tested in the chapters that follow.

1Trifle

chapter abstract

This chapter begins with lists compiled in Lincolnshire in the 1550s. These

lists show that objects including pyxes-containers for the Eucharist-were

given to children as playthings. The chapter links this practice to the

widespread discourse that sought to demean traditional religion as a mere

trifling with inane and worthless things, but it argues that the practice

of iconoclastic child's play differs from this polemic in that the object

actually lingers as a potential locus for newly emerging meanings. This

possibility is linked to the wider complexities surrounding the status of

trifles and inanities in the history of Christian thought and its

consistent inversions of value, as well as to the self-reflexive

interrogation of the status of trifles in the writings of Thomas More.

2Doll

chapter abstract

This chapter opens with a father in Cologne in the 1590s who snapped the

arms from a crucifix and gave it to his children as a toy. Returning to the

sermon by Edgeworth discussed in the preface, the chapter considers this

broken object as what Edgeworth calls an "idoll"-a hybridization of doll

and idoll. This possibility is linked to the wider presence of "holy dolls"

in medieval Christianity, but ultimately the doll is explored not as a

stable and readily identifiable category but as a way of conceiving of

ambiguous objects that may be more or less human at different moments and

subjected alternatingly to violence and care. The implications of this

possibility are explored in relation to a medieval Christ child, a broken

crucifix, and a contemporary representation of a shattered doll.

3Puppet

chapter abstract

This chapter opens with a movable image of a dove, representing the Holy

Spirit, that was made into a plaything in sixteenth century Germany. It

relates this specific object to a wider range of articulated and jointed

figures involved in late medieval piety that were often attacked as empty

puppets by reformers. It uses these objects to think not about puppets per

se but rather about the jointedness or constitutive brokenness of holy

things more broadly, particularly relics poised between the sacred and the

disgusting. These objects are related to the unstable place of playfulness

and the material in Erasmus's writings, and to the wider place of creative

breaking and the disgusting in modern art.

4Fetish

chapter abstract

This chapter opens with an ambiguous set of objects collected by a Dutch

woman named Margrieta van Varick and described as "Indian Babies," possibly

brought with her from the Dutch East Indies to New England, and relates

them to the practice of iconoclastic child's play in Malaysia. It

repositions iconoclastic child's play in a fraught colonial context and

asks how the play of other cultures is to be interpreted. Beginning with

ethnographic and psychoanalytic discussions of child's play by

Lévi-Strauss, Winnicott, and others, it then moves to consider the category

of the fetish as one that has long been intertwined with the status of

children and their playing. It uses the contested status of this

category-as an object both replete with, and devoid of, meaning-to

reconsider the fetish as plaything both in sixteenth-century Guinea and in

Adorno's writing on artworks and children's games.

5Play

chapter abstract

This chapter opens with a set of medieval wooden statues in Audley End

House in Essex that survived in part because they spent a period being used

by children as toys. It considers the uneven trajectories through which

these objects have passed-existing at different points as holy things,

playthings, and art-things-to consider the wider temporal narratives into

which play (and especially the playing of children) is often folded. It

considers the way in which educative and habituating schemes from Plato to

Renaissance figures such as Thomas Elyot and Montaigne involve the

interpretation of play as a linear process of habituation, but it argues

that these narratives involve a defensive simplification of the way in

which play can in fact unfold in and through time, an attempt to limit and

tame its meanings.

6Mask

chapter abstract

This chapter begins with a wooden doll from the seventeenth century that is

juxtaposed with the statues from Audley End considered in the previous

chapter on the basis of their equally fixed, impassive visages. This

feature is used to consider the way in which children, especially when at

play, have been seen as troublingly masked, inscrutable, alien beings. It

discusses accounts from the sixteenth century, notably John Harington's,

that recognize in play periods of vacant, blank, neutral time. It then

proceeds to an extended reading of Bruegel's painting Children's Games, and

especially a consideration of the reading of this work by the Nazi art

historian Hans Sedlmayr. This painting, and Sedlmayr's remarkable and

deeply disquieting account, are seen as encapsulating the ways in which

child's play's resistance to interpretation can provoke fear and horror-a

possibility linked to the periodic association of children with witchcraft

and demonic possession.

Conclusion: Toy

chapter abstract

The conclusion returns to the larger narratives into which play has often

been folded in order to reconsider them in relation to the complexities of

iconoclastic child's play. It suggests that neat temporalities in which

play and seriousness contrast and alternate with one another need to be

replaced with trajectories that have room for sudden alteration and

reversal. Drawing in part from the writings of Hans Blumenberg, Bruno

Latour, Michel Serres, Siegfried Kracauer, and Igor Kopytoff, it suggests

that we think of objects (including artworks) in terms of their "toy

potential"-the perennial possibility that an object might both come to be,

and cease to be, a plaything. The implications of this possibility are

illustrated via a reading of an episode from Spenser's Faerie Queene in

which a malevolent allegorical dragon is startlingly transformed into a

child's plaything.