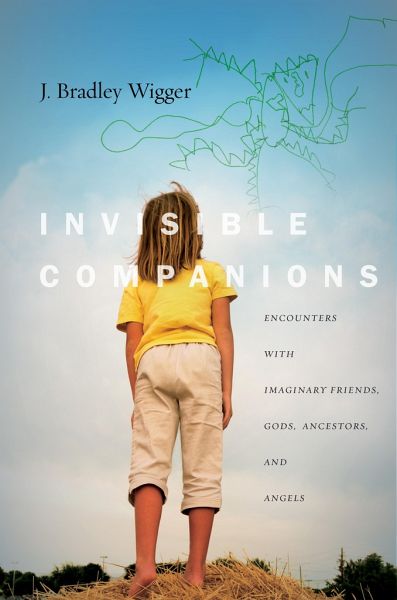

Invisible Companions

Encounters with Imaginary Friends, Gods, Ancestors, and Angels

Versandkostenfrei!

Versandfertig in über 4 Wochen

21,99 €

inkl. MwSt.

PAYBACK Punkte

11 °P sammeln!

J. Bradley Wigger teaches religious education and childhood studies at Louisville Seminary. An ordained Presbyterian minister and a recent Henry Luce III Fellow in Theology, Dr. Wigger has served churches in Colorado, Wisconsin, and Mexico. His most recent publications are the picture book for children, Thank You, God (2014), and Original Knowing: How Religion, Science, and the Human Mind Point to the Irreducible Depth of Life (2012).