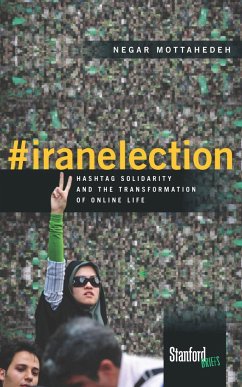

Negar Mottahedeh is Associate Professor in Literature and Women's Studies at Duke University. She is the author of Displaced Allegories: Post-Revolutionary Iranian Cinema (2008) and Representing the Unpresentable: Historical Images of National Reform from the Qajars to the Islamic Republic of Iran (2007).

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.