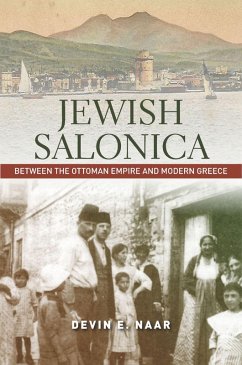

Touted as the "Jerusalem of the Balkans," the Mediterranean port city of Salonica (Thessaloniki) was once home to the largest Sephardic Jewish community in the world. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the city's incorporation into Greece in 1912 provoked a major upheaval that compelled Salonica's Jews to reimagine their community and status as citizens of a nation-state. Jewish Salonica is the first book to tell the story of this tumultuous transition through the voices and perspectives of Salonican Jews as they forged a new place for themselves in Greek society. Devin E. Naar traveled the globe, from New York to Salonica, Jerusalem, and Moscow, to excavate archives once confiscated by the Nazis. Written in Ladino, Greek, French, and Hebrew, these archives, combined with local newspapers, reveal how Salonica's Jews fashioned a new hybrid identity as Hellenic Jews during a period marked by rising nationalism and economic crisis as well as unprecedented Jewish cultural and political vibrancy. Salonica's Jews-Zionists, assimilationists, and socialists-reinvigorated their connection to the city and claimed it as their own until the Holocaust. Through the case of Salonica's Jews, Naar recovers the diverse experiences of a lost religious, linguistic, and national minority at the crossroads of Europe and the Middle East.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.