This fine colour facsimile, using the highest-standard digital techniques available, is accompanied by an introduction by Professor Martin Staehelin of the University of Göttingen and a scholarly commentary by Ian Rumbold with Peter Wright, both of the University of Nottingham, that provides a detailed codicological description of the manuscript and an analysis of its contents, together with a new inventory of the source. The introduction and commentary are being published in German and English.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

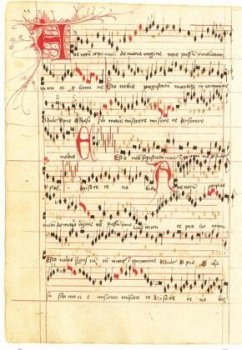

"In einem Faksimile-Band und einem Kommentarband wird der Codex lat. 14274 der BSB München präsentiert. Die Sammelhandschrift, die etwa zwischen 1430 und 1444 von dem Priester, Schulrektor und Handschriftensammler Hermann Pötzlinger (um 1415-1469) kompiliert und größtenteils von ihm selbst geschrieben wurde, ist die älteste im deutschen Sprachraum entstandene Sammlung internationaler mehrstimmiger Musik und mit 255 Stücken eine der umfangreichsten. Der Codex enthält vorwiegend geistliche Musik; weltliche (ursprünglich volkssprachliche) Kompositionen sind nur als Kontrafakturen, d.h. mit lateinischen geistlichen Texten unterlegt, in die Handschrift aufgenommen. Unter den zu identifizierenden Komponisten nimmt Guillaume de Machaut mit 40 Kompositionen den größten Raum ein; die meisten Werke sind allerdings anonym. Einige Werke von Komponisten aus dem deutschsprachigen Raum sind nur in diesem Codex überliefert; sie lassen sich vielfach mit Stationen aus Pötzlingers Biographie in Verbindung bringen. Der gesamte Kommentarband ist in deutscher und englischer Sprache verfasst; dem ausführlichen Kommentar gehen ein Vorwort von R. Grieber und eine Einführung von M. Staehlin voran. Der Kommentar selbst geht auf Forschungsberichte, Provenienz und Vorbesitzer des Codex (mit einer Kurzbiographie Pötzlingers), Einband, Etiketten und bibliothekarische Eintragungen, Papier und Foliierung, Liniierung und Notensysteme, Schreiberhände, musikalische Notation, Initialen und Rubrizierung, ein von Pötzlinger angelegten originalen Index und das Repertoire des Codex ein. Abbildungen zeigen im Faksimile nicht erkennbare Außenansichten, Spiegel und Falzstreifen (als Bindematerial wurde ein Codex mit grammatischen Texten, u.a. dem Grecismus der Eberhard von Béthune verwendet; die Blätter werden heute unter der Signatur lat. 14274a aufbewahrt), die Schrift Pötzlingers in anderen Codices sowie die vorhandenen Wasserzeichen. Den Abschluss des Bandes bildet ein Inventar des Codex mit folgenden Angaben zu jedem einzelnen Stück: Nr., Blatt, Komponist, Stimmenzahl, Gattung, Konkordanzen, Schreiber, Edition."

In: Medioevo Latino. 29 (2008). S. 484-485.

------------------------------------

"In recent years, projects to digitize or publish facsimiles of music manuscripts have increased in number, thereby helping to reduce the need for scholars to handle the fragile manuscripts directly. Such reproductions have also incited singers to perform directly from early notations and usefully substitute for early-notation textbooks (Willi Apel's 1942 classic, The Notation of Polyphonie Music, 900-1600, long reprinted by the Medieval Academy of America, is now out of print). At the same time they are transforming the disciplines of history and codicology, as well as musicology, by providing direct access to "wie es eigentlich gewesen" (in Ranke's words), in color.

This beautiful and relatively portable facsimile makes available for the first time the St. Emmeram Codex, from the library of that Benedictine abbey in Regensburg, now Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 14274. Mostly written between circa 1430 and 1448 by Magister Hermann Pötzlinger (d. 1469), a priest, rector of schools, and bibliophile who died at St. Emmeram, this choir book of 158 paper folios is the oldest collection of international polyphony known to have been written in Germany. The 255 monophonic and polyphonic sacred and secular compositions include 40 works by Guillaume Du Fay and others known in France, southern Germany, northern Italy, and Rome in the first third of the fifteenth century.

The facsimile is intended, above all, to replicate and thereby preserve the original, a timely concern given that folios 37-38 went missing in the 1950s (see p. 79; they are reproduced from a black-and-white microfilm). Thus the reproduced leaves are exactly the size of the originals, with a white border on which the folio (arabic) and gathering (roman) numbers are printed. (The number of the leaf within the gathering could have been included, as it is in the facsimile of the contemporaneous Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Canonici Misc. 213.) The quality of the reproduction is such that the ink of the other side of each leaf is neither more nor less prominent than in reality.

An implicit challenge was to produce editorial commentary that would be as timeless as the original manuscript, and therefore scrupulously accurate description takes pride of place over interpretation. Thus, in the foreword, Rolf Griebel, director of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, takes care to explain, for the historical record, the lengthy process of reproducing and digitizing the manuscript and the financial and scholarly collaboration. All texts accompanying the facsimile are published in German and English (translated by Leofranc Holford-Strevens).

In his introduction Martin Staehelin situates this manuscript among the large codices from the first half of the fifteenth century and their repertories. Emphasizing that Pötzlinger is the best represented of the four scribes, he argues that the manuscript did not result from a collector's penchant, nor was it intended for use in a church or chapel; instead, it was Pötzlinger's personal book, its uneven quality of notation challenging the modern editor. (Tom Ward is preparing an edition of the music.)

The commentary by Ian Rumbold with the collaboration of Peter Wright, a virtuoso mise au point, includes a history of scholarship on the manuscript and a thorough review of the codicological data: dates and descriptions of restorations, covers and binding material, bibliographical labels and inscriptions, paper, structure, foliations, staff rulings, scribes and methods of compilation, musical notation, and initials and rubrication. Included are an evaluation of the grammatical texts used as binding material and reconstituted during this project, tables of the distribution of paper types and watermarks, staff-

ruling patterns, scribes, attributable compositions and concordances, compositional types and repertorial clusters, and a transcription and analysis of the original index. The discussion of the notation is valuable because the manuscript is an important witness to the transition from black to white notation and to a wide range of notations ("ars subtilior," "stroke" notation, Gothic Hufnagelschrift, and central European signs), perhaps due to uncritical copying from exemplars, a topic left aside here, though it could be tested from concordances. Lost in the detail is basic information such as the dimensions of the manuscript-a short index would have helped. The only stones left unturned, however, are the erasures in the manuscript, which are not visible in the reproduction and were not reported because of their great number, as the authors acknowledge (p. 86).

The data presented, Rumbold and Wright next provide a concise and helpful summary, concluding that the manuscript belongs in a "socially modest priestly and academic environment rather than in the higher echelons of the church or court." (It could be compared with the similar, but earlier, Engelberg Codex 314, also available in color facsimile.) There follow a table of contents indicating known ascriptions or attributions, concordances, and editions; a list of cited nonmusical manuscripts, archival documents, music, and music theory manuscripts; and the bibliography, separating scholarly writings from editions of music. To the last, a recent book can be added: Thomas Emmerig, ed., Musikgeschichte Regensburgs (Regensburg, 2006), which includes David Hiley's discussion and transcriptions of Folios 10v and 155v of the codex.

This is surely one of the most beautiful and carefully prepared facsimiles of a paper music manuscript, and it sets a new standard for future facsimiles. It also confirms once again that often manuscripts lacking any decoration must be studied and saved for posterity because they contain treasures of great historical and artistic importance."

BARBARA HAGGH, University of Maryland

In: Speculum. 83 (4). Ocotber 2008. pp. 215-216.

---------------------------"The publication of the codex in facsimile marks a first culmination point in drawing this work together. (...)

The 150-page commentary volume, in English and German, provides a atate-of-the-art guide to the source. The bulk of it presents the first fruits of Rumbold and Wright's collaborative research. Ever anticipated aspect is touched upon, with physical makeup, scribes and compilation receiving particularly thorough treatment. A brief introduction by Martin Staehlin succinctly highlights the most important aspects of the codex's significance, and an extensive bibliography is provided. (...)

An influx in English music, by Dunstaple and Power among others, in the later layers of the codex reflects larger contemporary trends. It is not the international repertory, however, but the local, that makes the codex uniquely valuable and distinctive. (...) More than 100 works, however, are both anonymous and unknown outside the codex. New insights into this easily sidelined repertory will be among the most interesting avenues for further research. (...)

The facsimile itself is superb. The dource is presented at its original size, and runs complete from inside front-cover to inside back-cover in full colour apart from four now-lost pages that had to be recovered from microfilm. The high resolution renders even the subtlest details visible. (...)

Along with its companion-studies, the facsimile will undoubtedly make the St Emmeram codex less easy to overlook than it has been in the past. Thanks to all involved, it is on its way to becoming a central European source in every sense."

David J. Burn

In: Early Music. XXXVII (2009) 2. pp. 311-313.

-------------------------------

"Er ist eines der wichtigsten und umfangreichsten Denkmäler der mehrstimmigen Musik im deutschsprachigen Raum, das uns aus der ersten Hälfte des 15. Jahrhunderts erhalten ist." und: "Er ist die älteste Sammlung internationaler Mehrstimmigkeit im deutschen Sprachraum." Dr. Rolf Griebel, Generaldirektor der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, überschlug sich nur so mit Superlativen bei der Beschreibung des Mensuralcodex St. Emmeram.

Seit drei Jahrzehnten war es der Wunsch von Wissenschaft und Staatsbibliothek, ein hochwertiges Faksimile, das heißt eine originalgetreue Kopie, zu erstellen. Doch das Projekt scheiterte immer wieder an Finanzierungsfragen. Mit der Unterstützung durch die Oberfrankenstiftung kam aber der Durchbruch. Dazu gibt es einen deutschen und englischen Kommentar. Bei dem Reproduktionsverfahren wurde ausschließlich die digitale Technik angewandt. (...)

Der Mensuralcodex wurde von dem aus Bayreuth stammenden Lehrer und Pfarrer Hermann Pötzlinger seit der Zeit um 1430 angelegt. Die Papierhandschrift enthält 255 ein- und mehrstimmige Sätze geistlicher und weltlicher Musik. Pötzlinger verstarb 1469."

In: Nordbayerischer Kurier (Bayreuth) vom 3. Oktober 2007

-------------------------------

"Das Werk ist die älteste und umfangreichste Handschrift aus Deutschland mit überwiegend mehrstimmigen Sätzen mit geistlicher und weltlicher Musik aus Italien, Frankreich, den Niederlanden und England. Die im Reichert-Verlag erschienene, hochwertige Faksimile-Edition einer der wertvollsten und seltensten Musikhandschriften aus der ersten Hälfte des 15. Jahrhunderts wird durch einen deutschen und englischen Kommentar wissenschaftlich erschlossen. Die neuesten Ergebnisse eines in England abgeschlossenen großangelegten Forschungsprojekts über den Mensuralcodex konnten bereits einbezogen werden."

In: Erbe und Auftrag. Benediktinische Zeitschrift Monastische Welt. 84 (2008). Heft 2. S. 238.

In: Medioevo Latino. 29 (2008). S. 484-485.

------------------------------------

"In recent years, projects to digitize or publish facsimiles of music manuscripts have increased in number, thereby helping to reduce the need for scholars to handle the fragile manuscripts directly. Such reproductions have also incited singers to perform directly from early notations and usefully substitute for early-notation textbooks (Willi Apel's 1942 classic, The Notation of Polyphonie Music, 900-1600, long reprinted by the Medieval Academy of America, is now out of print). At the same time they are transforming the disciplines of history and codicology, as well as musicology, by providing direct access to "wie es eigentlich gewesen" (in Ranke's words), in color.

This beautiful and relatively portable facsimile makes available for the first time the St. Emmeram Codex, from the library of that Benedictine abbey in Regensburg, now Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 14274. Mostly written between circa 1430 and 1448 by Magister Hermann Pötzlinger (d. 1469), a priest, rector of schools, and bibliophile who died at St. Emmeram, this choir book of 158 paper folios is the oldest collection of international polyphony known to have been written in Germany. The 255 monophonic and polyphonic sacred and secular compositions include 40 works by Guillaume Du Fay and others known in France, southern Germany, northern Italy, and Rome in the first third of the fifteenth century.

The facsimile is intended, above all, to replicate and thereby preserve the original, a timely concern given that folios 37-38 went missing in the 1950s (see p. 79; they are reproduced from a black-and-white microfilm). Thus the reproduced leaves are exactly the size of the originals, with a white border on which the folio (arabic) and gathering (roman) numbers are printed. (The number of the leaf within the gathering could have been included, as it is in the facsimile of the contemporaneous Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Canonici Misc. 213.) The quality of the reproduction is such that the ink of the other side of each leaf is neither more nor less prominent than in reality.

An implicit challenge was to produce editorial commentary that would be as timeless as the original manuscript, and therefore scrupulously accurate description takes pride of place over interpretation. Thus, in the foreword, Rolf Griebel, director of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, takes care to explain, for the historical record, the lengthy process of reproducing and digitizing the manuscript and the financial and scholarly collaboration. All texts accompanying the facsimile are published in German and English (translated by Leofranc Holford-Strevens).

In his introduction Martin Staehelin situates this manuscript among the large codices from the first half of the fifteenth century and their repertories. Emphasizing that Pötzlinger is the best represented of the four scribes, he argues that the manuscript did not result from a collector's penchant, nor was it intended for use in a church or chapel; instead, it was Pötzlinger's personal book, its uneven quality of notation challenging the modern editor. (Tom Ward is preparing an edition of the music.)

The commentary by Ian Rumbold with the collaboration of Peter Wright, a virtuoso mise au point, includes a history of scholarship on the manuscript and a thorough review of the codicological data: dates and descriptions of restorations, covers and binding material, bibliographical labels and inscriptions, paper, structure, foliations, staff rulings, scribes and methods of compilation, musical notation, and initials and rubrication. Included are an evaluation of the grammatical texts used as binding material and reconstituted during this project, tables of the distribution of paper types and watermarks, staff-

ruling patterns, scribes, attributable compositions and concordances, compositional types and repertorial clusters, and a transcription and analysis of the original index. The discussion of the notation is valuable because the manuscript is an important witness to the transition from black to white notation and to a wide range of notations ("ars subtilior," "stroke" notation, Gothic Hufnagelschrift, and central European signs), perhaps due to uncritical copying from exemplars, a topic left aside here, though it could be tested from concordances. Lost in the detail is basic information such as the dimensions of the manuscript-a short index would have helped. The only stones left unturned, however, are the erasures in the manuscript, which are not visible in the reproduction and were not reported because of their great number, as the authors acknowledge (p. 86).

The data presented, Rumbold and Wright next provide a concise and helpful summary, concluding that the manuscript belongs in a "socially modest priestly and academic environment rather than in the higher echelons of the church or court." (It could be compared with the similar, but earlier, Engelberg Codex 314, also available in color facsimile.) There follow a table of contents indicating known ascriptions or attributions, concordances, and editions; a list of cited nonmusical manuscripts, archival documents, music, and music theory manuscripts; and the bibliography, separating scholarly writings from editions of music. To the last, a recent book can be added: Thomas Emmerig, ed., Musikgeschichte Regensburgs (Regensburg, 2006), which includes David Hiley's discussion and transcriptions of Folios 10v and 155v of the codex.

This is surely one of the most beautiful and carefully prepared facsimiles of a paper music manuscript, and it sets a new standard for future facsimiles. It also confirms once again that often manuscripts lacking any decoration must be studied and saved for posterity because they contain treasures of great historical and artistic importance."

BARBARA HAGGH, University of Maryland

In: Speculum. 83 (4). Ocotber 2008. pp. 215-216.

---------------------------"The publication of the codex in facsimile marks a first culmination point in drawing this work together. (...)

The 150-page commentary volume, in English and German, provides a atate-of-the-art guide to the source. The bulk of it presents the first fruits of Rumbold and Wright's collaborative research. Ever anticipated aspect is touched upon, with physical makeup, scribes and compilation receiving particularly thorough treatment. A brief introduction by Martin Staehlin succinctly highlights the most important aspects of the codex's significance, and an extensive bibliography is provided. (...)

An influx in English music, by Dunstaple and Power among others, in the later layers of the codex reflects larger contemporary trends. It is not the international repertory, however, but the local, that makes the codex uniquely valuable and distinctive. (...) More than 100 works, however, are both anonymous and unknown outside the codex. New insights into this easily sidelined repertory will be among the most interesting avenues for further research. (...)

The facsimile itself is superb. The dource is presented at its original size, and runs complete from inside front-cover to inside back-cover in full colour apart from four now-lost pages that had to be recovered from microfilm. The high resolution renders even the subtlest details visible. (...)

Along with its companion-studies, the facsimile will undoubtedly make the St Emmeram codex less easy to overlook than it has been in the past. Thanks to all involved, it is on its way to becoming a central European source in every sense."

David J. Burn

In: Early Music. XXXVII (2009) 2. pp. 311-313.

-------------------------------

"Er ist eines der wichtigsten und umfangreichsten Denkmäler der mehrstimmigen Musik im deutschsprachigen Raum, das uns aus der ersten Hälfte des 15. Jahrhunderts erhalten ist." und: "Er ist die älteste Sammlung internationaler Mehrstimmigkeit im deutschen Sprachraum." Dr. Rolf Griebel, Generaldirektor der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, überschlug sich nur so mit Superlativen bei der Beschreibung des Mensuralcodex St. Emmeram.

Seit drei Jahrzehnten war es der Wunsch von Wissenschaft und Staatsbibliothek, ein hochwertiges Faksimile, das heißt eine originalgetreue Kopie, zu erstellen. Doch das Projekt scheiterte immer wieder an Finanzierungsfragen. Mit der Unterstützung durch die Oberfrankenstiftung kam aber der Durchbruch. Dazu gibt es einen deutschen und englischen Kommentar. Bei dem Reproduktionsverfahren wurde ausschließlich die digitale Technik angewandt. (...)

Der Mensuralcodex wurde von dem aus Bayreuth stammenden Lehrer und Pfarrer Hermann Pötzlinger seit der Zeit um 1430 angelegt. Die Papierhandschrift enthält 255 ein- und mehrstimmige Sätze geistlicher und weltlicher Musik. Pötzlinger verstarb 1469."

In: Nordbayerischer Kurier (Bayreuth) vom 3. Oktober 2007

-------------------------------

"Das Werk ist die älteste und umfangreichste Handschrift aus Deutschland mit überwiegend mehrstimmigen Sätzen mit geistlicher und weltlicher Musik aus Italien, Frankreich, den Niederlanden und England. Die im Reichert-Verlag erschienene, hochwertige Faksimile-Edition einer der wertvollsten und seltensten Musikhandschriften aus der ersten Hälfte des 15. Jahrhunderts wird durch einen deutschen und englischen Kommentar wissenschaftlich erschlossen. Die neuesten Ergebnisse eines in England abgeschlossenen großangelegten Forschungsprojekts über den Mensuralcodex konnten bereits einbezogen werden."

In: Erbe und Auftrag. Benediktinische Zeitschrift Monastische Welt. 84 (2008). Heft 2. S. 238.