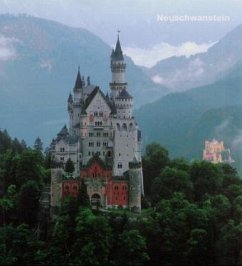

Anderthalb Millionen Besucher im Jahr können nicht irren. Für sie ist das bayerische Königsschloss Neuschwanstein die Erfüllung aller architektonischen Märchenträume. Für die architektonisch Gebil-deten aber, für die Adepten der Moderne, ist das stilistisch krude, anachronistische Monument einer Fürstenlaune nur ein Ärgernis. Läßt man freilich einmal alle positiven oder negativen Vorurteile beiseite, dann kommt man nicht umhin, die romantische Neuschöpfung einer mittelalterlichen Burg in atemberaubender Aussichtslage zu den spektakulärsten Pionierbauten des europäischen Historismus zu zählen. Neuschwanstein ist ein Extrem: Nie zuvor sind die Reize der umgehenden Natur und die Tektonik der Landschaft so bewusst als Wirkungsmittel im architektonischen Gesamtbild eingesetzt worden. Nie sind historistische Architekturformen mit so viel exis-tenziellem Sinn aufgeladen worden wie von König Ludwig II., der glaubte, sich durch schieres Bauen in ritterliche Heldenzeiten zurück versetzen zu können. Und nie wieder ist Architektur so unumwunden als Bühnenbild in den Dienst einer theatralischen Lebensinszenierung gestellt, also von ihren ursprünglichen Funktionen befreit worden. Ludwig ist bei seinem Rückzug aus der Wirklichkeit in Bereiche des Märchens vorgestoßen, die der Architektur sonst verschlossen geblieben wären. Man könnte also sagen: So wie die hierarchisch gestufte Welt von Versailles ein gebautes Sinnbild der barock-absolutistischen Staatsordnung ist, so ist die auf ihrer Bergspitze fast unzugängliche Wohnburg Neuschwanstein ein Sinnbild für die Weltferne eines königlichen Träumers, der seiner anachronistischen Existenz durch Flucht in die Fiktion und durch Rückgriffe in die gloriose Vergangenheit einen Sinn geben wollte.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.