- Gebundenes Buch

- Merkliste

- Auf die Merkliste

- Bewerten Bewerten

- Teilen

- Produkt teilen

- Produkterinnerung

- Produkterinnerung

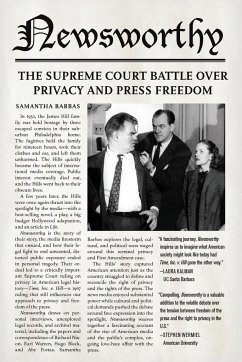

Samantha Barbas is Professor of Law at University at Buffalo Law School. She is the author of three books: Movie Crazy: Fans, Stars, and the Cult of Celebrity (2001), The First Lady of Hollywood: A Biography of Louella Parsons (2005), and Laws of Image (Stanford, 2015). She has provided legal commentary for The New York Times, The Guardian, and The Washington Post.

Andere Kunden interessierten sich auch für

![Pot for Profit Pot for Profit]() Joseph MelloPot for Profit129,99 €

Joseph MelloPot for Profit129,99 €![The Legality of Boxing The Legality of Boxing]() Jack AndersonThe Legality of Boxing235,99 €

Jack AndersonThe Legality of Boxing235,99 €![A New Megasport Legacy A New Megasport Legacy]() Andrew SpaldingA New Megasport Legacy167,99 €

Andrew SpaldingA New Megasport Legacy167,99 €![Law by Night Law by Night]() Jonathan Goldberg-HillerLaw by Night132,99 €

Jonathan Goldberg-HillerLaw by Night132,99 €![The Judge on the Screen The Judge on the Screen]() Vincenzo TomeoThe Judge on the Screen124,99 €

Vincenzo TomeoThe Judge on the Screen124,99 €![Sovereign Power and the Law in China Sovereign Power and the Law in China]() Flora SapioSovereign Power and the Law in China244,99 €

Flora SapioSovereign Power and the Law in China244,99 €![Anarchism & Sexuality Anarchism & Sexuality]() Anarchism & Sexuality229,99 €

Anarchism & Sexuality229,99 €-

-

-

Samantha Barbas is Professor of Law at University at Buffalo Law School. She is the author of three books: Movie Crazy: Fans, Stars, and the Cult of Celebrity (2001), The First Lady of Hollywood: A Biography of Louella Parsons (2005), and Laws of Image (Stanford, 2015). She has provided legal commentary for The New York Times, The Guardian, and The Washington Post.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Produktdetails

- Produktdetails

- Verlag: Stanford University Press

- Seitenzahl: 352

- Erscheinungstermin: 18. Januar 2017

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 231mm x 160mm x 30mm

- Gewicht: 599g

- ISBN-13: 9780804797108

- ISBN-10: 0804797102

- Artikelnr.: 45000912

- Herstellerkennzeichnung

- Produktsicherheitsverantwortliche/r

- Europaallee 1

- 36244 Bad Hersfeld

- gpsr@libri.de

- Verlag: Stanford University Press

- Seitenzahl: 352

- Erscheinungstermin: 18. Januar 2017

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 231mm x 160mm x 30mm

- Gewicht: 599g

- ISBN-13: 9780804797108

- ISBN-10: 0804797102

- Artikelnr.: 45000912

- Herstellerkennzeichnung

- Produktsicherheitsverantwortliche/r

- Europaallee 1

- 36244 Bad Hersfeld

- gpsr@libri.de

Samantha Barbas is Professor of Law at University at Buffalo Law School. She is the author of three books: Movie Crazy: Fans, Stars, and the Cult of Celebrity (2001), The First Lady of Hollywood: A Biography of Louella Parsons (2005), and Laws of Image (Stanford, 2015). She has provided legal commentary for The New York Times, The Guardian, and The Washington Post.

Contents and Abstracts

1The Whitemarsh Incident

chapter abstract

This chapter describes the "hostage incident" that initiated the Time, Inc.

v. Hill case. In 1952, the James Hill family was held hostage in their home

by three escaped convicts, who left without harming them. The story of the

crime was written up in the press, and the incident inspired a novel, play,

and film titled The Desperate Hours.

2Fact into Fiction

chapter abstract

In 1954, Joseph Hayes wrote The Desperate Hours, a "true-crime thriller"

based loosely on the hostage incident involving the Hill family. The

Desperate Hours became a bestseller; it was adapted into a play, and in

1955, a Hollywood film starring Humphrey Bogart.

3The Article

chapter abstract

In 1955, Life magazine published an article announcing the opening of the

play The Desperate Hours. The article falsely described the play as a

"reenactment" of the Hills' hostage incident. This chapter tells the story

of the writing of the article, and gives background information on Life's

publisher, Time, Inc. It describes the Hills' reaction to the article,

which thrust them into the spotlight against their will and portrayed them

in a false, distorted context.

4The Lawsuit

chapter abstract

Shortly after the publication of the Life article, James Hill filed suit

against Time, Inc., alleging an invasion of his privacy. The Hill family

was represented by Leonard Garment, a young, up-and-coming lawyer at the

New York law firm Mudge, Stern, Baldwin, and Todd.

5Privacy

chapter abstract

This chapter describes the origins of the tort action for invasion of

privacy, the basis of the Hills' lawsuit against Time, Inc.

6Freedom of the Press

chapter abstract

At the same time the right to privacy was developing in the early twentieth

century, courts were limiting the privacy tort in the interest in freedom

of the press. By the 1950s, the right to privacy and freedom of the press

were on a collision course, and the Hills' case would be at their juncture.

7Suing the Press

chapter abstract

This chapter describes Time, Inc.'s response to the Hills' lawsuit, and the

legal department at Time, Inc. In the mid-twentieth century, lawyers at

major media companies like Time, Inc. were major forces in the creation of

modern First Amendment law.

8Maneuvers

chapter abstract

This chapter describes the ongoing impact of the Life article on the Hill

family, the initial stages of the Hills' lawsuit, and the contested social

terrain on which it was fought. In the 1950s, some courts, against the

backdrop of increasing anti-press sentiment, were expanding the privacy

tort. Others, reflecting growing sensitivities towards civil liberties in

the postwar era, were diminishing the right to privacy in the name of First

Amendment freedoms.

9The Trial

chapter abstract

In the trial of Hill v. Hayes in 1962, a jury concluded that Time, Inc. had

invaded the privacy of the Hill family and awarded them $175,000, the

largest invasion of privacy verdict in history.

10The Privacy Panic

chapter abstract

The Hills' lawsuit against Time, Inc. took place at a time of great anxiety

around personal privacy. In the 1950s and 60s, "privacy," in all its

meanings and senses, was seemingly under assault by an array of forces: the

media, the government, researchers, advertisers, and marketers, armed with

new surveillance and monitoring technologies. There was a "privacy panic"

in the postwar era, and it influenced the course of the Hill case.

11Appeals

chapter abstract

In May 1963, an appeals court upheld the judgment against Time, Inc.

12Griswold

chapter abstract

Shortly after Time, Inc. announced its intent to appeal to the U.S. Supreme

Court in 1965, the Court issued its decision in Griswold v. Connecticut,

announcing a "right to privacy" in the Fourteenth Amendment and the Bill of

Rights. Like New York Times v. Sullivan, Griswold complicated the Hill

case. Not only a right protected by tort law, privacy was now potentially a

broad, general right guaranteed by the Constitution.

13Nixon

chapter abstract

In 1965, the Hills acquired an unexpected advocate. Two years earlier, the

former Senator, Vice-President, and presidential candidate Richard Nixon

joined the Mudge law firm. Nixon would argue the Hills' case before the

Supreme Court. The case became an integral part of Nixon's efforts to

rehabilitate his public image during his "Wilderness Years," the six-year

span between his failed run for the California governorship in 1962 and his

election as President in 1968.

14At the Court

chapter abstract

Against the backdrop of cultural concerns with privacy and press ethics,

and in the shadow of Sullivan and Griswold, Time, Inc. v. Hill came to the

Supreme Court freighted with a good deal of significance. The case tapped

into pressing social issues: the future of privacy in the information

society, the meaning of "the news," the boundaries of freedom of the press

in the age of big media. It also raised questions of constitutional

doctrine that were contested on the Court - the status of the

constitutional right to privacy, and possible extensions of the New York

Times v. Sullivan doctrine.

15Decisions

chapter abstract

After arguments by Nixon and Harold R. Medina, Jr., representing Time,

Inc., the Supreme Court initially came down on the side of privacy. A 6-3

majority decided in favor of the Hills, upholding the judgment of the New

York courts. Expanding the "right to privacy" established in the Griswold

decision, the majority opinion, written by Justice Abe Fortas, declared

that the Hills had a constitutional right to privacy that could be invoked

not only against the government, but also private actors like the press.

Ultimately, however, the Court changed its mind. As a result of lobbying by

Justice Hugo Black, a First Amendment absolutist, votes switched, and a new

majority voted in favor of Time, Inc.

16January 9, 1967

chapter abstract

William Brennan wrote the majority opinion in Time, Inc. v. Hill, issued in

January 1967. Invoking the New York Times v. Sullivan standard, Brennan

held that the Hills could not recover for invasion of privacy unless they

could show that Life's story about them was false, and that the falsehood

was made with reckless disregard of the truth. The Brennan opinion

announced a capacious vision of freedom of the press, perhaps the broadest

in the Supreme Court's history to that time.

17The Aftermath

chapter abstract

Time, Inc. v. Hill transformed the meaning of freedom of the press and the

scope of the right to privacy in the United States. Time, Inc. v. Hill set

forth an expansive vision of freedom of the press and dimmed the potential

for a strong right to privacy that could be invoked against the press. This

chapter examines the short and long-term consequences of the Hill decision

on politics, publishing, and the First Amendment.

1The Whitemarsh Incident

chapter abstract

This chapter describes the "hostage incident" that initiated the Time, Inc.

v. Hill case. In 1952, the James Hill family was held hostage in their home

by three escaped convicts, who left without harming them. The story of the

crime was written up in the press, and the incident inspired a novel, play,

and film titled The Desperate Hours.

2Fact into Fiction

chapter abstract

In 1954, Joseph Hayes wrote The Desperate Hours, a "true-crime thriller"

based loosely on the hostage incident involving the Hill family. The

Desperate Hours became a bestseller; it was adapted into a play, and in

1955, a Hollywood film starring Humphrey Bogart.

3The Article

chapter abstract

In 1955, Life magazine published an article announcing the opening of the

play The Desperate Hours. The article falsely described the play as a

"reenactment" of the Hills' hostage incident. This chapter tells the story

of the writing of the article, and gives background information on Life's

publisher, Time, Inc. It describes the Hills' reaction to the article,

which thrust them into the spotlight against their will and portrayed them

in a false, distorted context.

4The Lawsuit

chapter abstract

Shortly after the publication of the Life article, James Hill filed suit

against Time, Inc., alleging an invasion of his privacy. The Hill family

was represented by Leonard Garment, a young, up-and-coming lawyer at the

New York law firm Mudge, Stern, Baldwin, and Todd.

5Privacy

chapter abstract

This chapter describes the origins of the tort action for invasion of

privacy, the basis of the Hills' lawsuit against Time, Inc.

6Freedom of the Press

chapter abstract

At the same time the right to privacy was developing in the early twentieth

century, courts were limiting the privacy tort in the interest in freedom

of the press. By the 1950s, the right to privacy and freedom of the press

were on a collision course, and the Hills' case would be at their juncture.

7Suing the Press

chapter abstract

This chapter describes Time, Inc.'s response to the Hills' lawsuit, and the

legal department at Time, Inc. In the mid-twentieth century, lawyers at

major media companies like Time, Inc. were major forces in the creation of

modern First Amendment law.

8Maneuvers

chapter abstract

This chapter describes the ongoing impact of the Life article on the Hill

family, the initial stages of the Hills' lawsuit, and the contested social

terrain on which it was fought. In the 1950s, some courts, against the

backdrop of increasing anti-press sentiment, were expanding the privacy

tort. Others, reflecting growing sensitivities towards civil liberties in

the postwar era, were diminishing the right to privacy in the name of First

Amendment freedoms.

9The Trial

chapter abstract

In the trial of Hill v. Hayes in 1962, a jury concluded that Time, Inc. had

invaded the privacy of the Hill family and awarded them $175,000, the

largest invasion of privacy verdict in history.

10The Privacy Panic

chapter abstract

The Hills' lawsuit against Time, Inc. took place at a time of great anxiety

around personal privacy. In the 1950s and 60s, "privacy," in all its

meanings and senses, was seemingly under assault by an array of forces: the

media, the government, researchers, advertisers, and marketers, armed with

new surveillance and monitoring technologies. There was a "privacy panic"

in the postwar era, and it influenced the course of the Hill case.

11Appeals

chapter abstract

In May 1963, an appeals court upheld the judgment against Time, Inc.

12Griswold

chapter abstract

Shortly after Time, Inc. announced its intent to appeal to the U.S. Supreme

Court in 1965, the Court issued its decision in Griswold v. Connecticut,

announcing a "right to privacy" in the Fourteenth Amendment and the Bill of

Rights. Like New York Times v. Sullivan, Griswold complicated the Hill

case. Not only a right protected by tort law, privacy was now potentially a

broad, general right guaranteed by the Constitution.

13Nixon

chapter abstract

In 1965, the Hills acquired an unexpected advocate. Two years earlier, the

former Senator, Vice-President, and presidential candidate Richard Nixon

joined the Mudge law firm. Nixon would argue the Hills' case before the

Supreme Court. The case became an integral part of Nixon's efforts to

rehabilitate his public image during his "Wilderness Years," the six-year

span between his failed run for the California governorship in 1962 and his

election as President in 1968.

14At the Court

chapter abstract

Against the backdrop of cultural concerns with privacy and press ethics,

and in the shadow of Sullivan and Griswold, Time, Inc. v. Hill came to the

Supreme Court freighted with a good deal of significance. The case tapped

into pressing social issues: the future of privacy in the information

society, the meaning of "the news," the boundaries of freedom of the press

in the age of big media. It also raised questions of constitutional

doctrine that were contested on the Court - the status of the

constitutional right to privacy, and possible extensions of the New York

Times v. Sullivan doctrine.

15Decisions

chapter abstract

After arguments by Nixon and Harold R. Medina, Jr., representing Time,

Inc., the Supreme Court initially came down on the side of privacy. A 6-3

majority decided in favor of the Hills, upholding the judgment of the New

York courts. Expanding the "right to privacy" established in the Griswold

decision, the majority opinion, written by Justice Abe Fortas, declared

that the Hills had a constitutional right to privacy that could be invoked

not only against the government, but also private actors like the press.

Ultimately, however, the Court changed its mind. As a result of lobbying by

Justice Hugo Black, a First Amendment absolutist, votes switched, and a new

majority voted in favor of Time, Inc.

16January 9, 1967

chapter abstract

William Brennan wrote the majority opinion in Time, Inc. v. Hill, issued in

January 1967. Invoking the New York Times v. Sullivan standard, Brennan

held that the Hills could not recover for invasion of privacy unless they

could show that Life's story about them was false, and that the falsehood

was made with reckless disregard of the truth. The Brennan opinion

announced a capacious vision of freedom of the press, perhaps the broadest

in the Supreme Court's history to that time.

17The Aftermath

chapter abstract

Time, Inc. v. Hill transformed the meaning of freedom of the press and the

scope of the right to privacy in the United States. Time, Inc. v. Hill set

forth an expansive vision of freedom of the press and dimmed the potential

for a strong right to privacy that could be invoked against the press. This

chapter examines the short and long-term consequences of the Hill decision

on politics, publishing, and the First Amendment.

Contents and Abstracts

1The Whitemarsh Incident

chapter abstract

This chapter describes the "hostage incident" that initiated the Time, Inc.

v. Hill case. In 1952, the James Hill family was held hostage in their home

by three escaped convicts, who left without harming them. The story of the

crime was written up in the press, and the incident inspired a novel, play,

and film titled The Desperate Hours.

2Fact into Fiction

chapter abstract

In 1954, Joseph Hayes wrote The Desperate Hours, a "true-crime thriller"

based loosely on the hostage incident involving the Hill family. The

Desperate Hours became a bestseller; it was adapted into a play, and in

1955, a Hollywood film starring Humphrey Bogart.

3The Article

chapter abstract

In 1955, Life magazine published an article announcing the opening of the

play The Desperate Hours. The article falsely described the play as a

"reenactment" of the Hills' hostage incident. This chapter tells the story

of the writing of the article, and gives background information on Life's

publisher, Time, Inc. It describes the Hills' reaction to the article,

which thrust them into the spotlight against their will and portrayed them

in a false, distorted context.

4The Lawsuit

chapter abstract

Shortly after the publication of the Life article, James Hill filed suit

against Time, Inc., alleging an invasion of his privacy. The Hill family

was represented by Leonard Garment, a young, up-and-coming lawyer at the

New York law firm Mudge, Stern, Baldwin, and Todd.

5Privacy

chapter abstract

This chapter describes the origins of the tort action for invasion of

privacy, the basis of the Hills' lawsuit against Time, Inc.

6Freedom of the Press

chapter abstract

At the same time the right to privacy was developing in the early twentieth

century, courts were limiting the privacy tort in the interest in freedom

of the press. By the 1950s, the right to privacy and freedom of the press

were on a collision course, and the Hills' case would be at their juncture.

7Suing the Press

chapter abstract

This chapter describes Time, Inc.'s response to the Hills' lawsuit, and the

legal department at Time, Inc. In the mid-twentieth century, lawyers at

major media companies like Time, Inc. were major forces in the creation of

modern First Amendment law.

8Maneuvers

chapter abstract

This chapter describes the ongoing impact of the Life article on the Hill

family, the initial stages of the Hills' lawsuit, and the contested social

terrain on which it was fought. In the 1950s, some courts, against the

backdrop of increasing anti-press sentiment, were expanding the privacy

tort. Others, reflecting growing sensitivities towards civil liberties in

the postwar era, were diminishing the right to privacy in the name of First

Amendment freedoms.

9The Trial

chapter abstract

In the trial of Hill v. Hayes in 1962, a jury concluded that Time, Inc. had

invaded the privacy of the Hill family and awarded them $175,000, the

largest invasion of privacy verdict in history.

10The Privacy Panic

chapter abstract

The Hills' lawsuit against Time, Inc. took place at a time of great anxiety

around personal privacy. In the 1950s and 60s, "privacy," in all its

meanings and senses, was seemingly under assault by an array of forces: the

media, the government, researchers, advertisers, and marketers, armed with

new surveillance and monitoring technologies. There was a "privacy panic"

in the postwar era, and it influenced the course of the Hill case.

11Appeals

chapter abstract

In May 1963, an appeals court upheld the judgment against Time, Inc.

12Griswold

chapter abstract

Shortly after Time, Inc. announced its intent to appeal to the U.S. Supreme

Court in 1965, the Court issued its decision in Griswold v. Connecticut,

announcing a "right to privacy" in the Fourteenth Amendment and the Bill of

Rights. Like New York Times v. Sullivan, Griswold complicated the Hill

case. Not only a right protected by tort law, privacy was now potentially a

broad, general right guaranteed by the Constitution.

13Nixon

chapter abstract

In 1965, the Hills acquired an unexpected advocate. Two years earlier, the

former Senator, Vice-President, and presidential candidate Richard Nixon

joined the Mudge law firm. Nixon would argue the Hills' case before the

Supreme Court. The case became an integral part of Nixon's efforts to

rehabilitate his public image during his "Wilderness Years," the six-year

span between his failed run for the California governorship in 1962 and his

election as President in 1968.

14At the Court

chapter abstract

Against the backdrop of cultural concerns with privacy and press ethics,

and in the shadow of Sullivan and Griswold, Time, Inc. v. Hill came to the

Supreme Court freighted with a good deal of significance. The case tapped

into pressing social issues: the future of privacy in the information

society, the meaning of "the news," the boundaries of freedom of the press

in the age of big media. It also raised questions of constitutional

doctrine that were contested on the Court - the status of the

constitutional right to privacy, and possible extensions of the New York

Times v. Sullivan doctrine.

15Decisions

chapter abstract

After arguments by Nixon and Harold R. Medina, Jr., representing Time,

Inc., the Supreme Court initially came down on the side of privacy. A 6-3

majority decided in favor of the Hills, upholding the judgment of the New

York courts. Expanding the "right to privacy" established in the Griswold

decision, the majority opinion, written by Justice Abe Fortas, declared

that the Hills had a constitutional right to privacy that could be invoked

not only against the government, but also private actors like the press.

Ultimately, however, the Court changed its mind. As a result of lobbying by

Justice Hugo Black, a First Amendment absolutist, votes switched, and a new

majority voted in favor of Time, Inc.

16January 9, 1967

chapter abstract

William Brennan wrote the majority opinion in Time, Inc. v. Hill, issued in

January 1967. Invoking the New York Times v. Sullivan standard, Brennan

held that the Hills could not recover for invasion of privacy unless they

could show that Life's story about them was false, and that the falsehood

was made with reckless disregard of the truth. The Brennan opinion

announced a capacious vision of freedom of the press, perhaps the broadest

in the Supreme Court's history to that time.

17The Aftermath

chapter abstract

Time, Inc. v. Hill transformed the meaning of freedom of the press and the

scope of the right to privacy in the United States. Time, Inc. v. Hill set

forth an expansive vision of freedom of the press and dimmed the potential

for a strong right to privacy that could be invoked against the press. This

chapter examines the short and long-term consequences of the Hill decision

on politics, publishing, and the First Amendment.

1The Whitemarsh Incident

chapter abstract

This chapter describes the "hostage incident" that initiated the Time, Inc.

v. Hill case. In 1952, the James Hill family was held hostage in their home

by three escaped convicts, who left without harming them. The story of the

crime was written up in the press, and the incident inspired a novel, play,

and film titled The Desperate Hours.

2Fact into Fiction

chapter abstract

In 1954, Joseph Hayes wrote The Desperate Hours, a "true-crime thriller"

based loosely on the hostage incident involving the Hill family. The

Desperate Hours became a bestseller; it was adapted into a play, and in

1955, a Hollywood film starring Humphrey Bogart.

3The Article

chapter abstract

In 1955, Life magazine published an article announcing the opening of the

play The Desperate Hours. The article falsely described the play as a

"reenactment" of the Hills' hostage incident. This chapter tells the story

of the writing of the article, and gives background information on Life's

publisher, Time, Inc. It describes the Hills' reaction to the article,

which thrust them into the spotlight against their will and portrayed them

in a false, distorted context.

4The Lawsuit

chapter abstract

Shortly after the publication of the Life article, James Hill filed suit

against Time, Inc., alleging an invasion of his privacy. The Hill family

was represented by Leonard Garment, a young, up-and-coming lawyer at the

New York law firm Mudge, Stern, Baldwin, and Todd.

5Privacy

chapter abstract

This chapter describes the origins of the tort action for invasion of

privacy, the basis of the Hills' lawsuit against Time, Inc.

6Freedom of the Press

chapter abstract

At the same time the right to privacy was developing in the early twentieth

century, courts were limiting the privacy tort in the interest in freedom

of the press. By the 1950s, the right to privacy and freedom of the press

were on a collision course, and the Hills' case would be at their juncture.

7Suing the Press

chapter abstract

This chapter describes Time, Inc.'s response to the Hills' lawsuit, and the

legal department at Time, Inc. In the mid-twentieth century, lawyers at

major media companies like Time, Inc. were major forces in the creation of

modern First Amendment law.

8Maneuvers

chapter abstract

This chapter describes the ongoing impact of the Life article on the Hill

family, the initial stages of the Hills' lawsuit, and the contested social

terrain on which it was fought. In the 1950s, some courts, against the

backdrop of increasing anti-press sentiment, were expanding the privacy

tort. Others, reflecting growing sensitivities towards civil liberties in

the postwar era, were diminishing the right to privacy in the name of First

Amendment freedoms.

9The Trial

chapter abstract

In the trial of Hill v. Hayes in 1962, a jury concluded that Time, Inc. had

invaded the privacy of the Hill family and awarded them $175,000, the

largest invasion of privacy verdict in history.

10The Privacy Panic

chapter abstract

The Hills' lawsuit against Time, Inc. took place at a time of great anxiety

around personal privacy. In the 1950s and 60s, "privacy," in all its

meanings and senses, was seemingly under assault by an array of forces: the

media, the government, researchers, advertisers, and marketers, armed with

new surveillance and monitoring technologies. There was a "privacy panic"

in the postwar era, and it influenced the course of the Hill case.

11Appeals

chapter abstract

In May 1963, an appeals court upheld the judgment against Time, Inc.

12Griswold

chapter abstract

Shortly after Time, Inc. announced its intent to appeal to the U.S. Supreme

Court in 1965, the Court issued its decision in Griswold v. Connecticut,

announcing a "right to privacy" in the Fourteenth Amendment and the Bill of

Rights. Like New York Times v. Sullivan, Griswold complicated the Hill

case. Not only a right protected by tort law, privacy was now potentially a

broad, general right guaranteed by the Constitution.

13Nixon

chapter abstract

In 1965, the Hills acquired an unexpected advocate. Two years earlier, the

former Senator, Vice-President, and presidential candidate Richard Nixon

joined the Mudge law firm. Nixon would argue the Hills' case before the

Supreme Court. The case became an integral part of Nixon's efforts to

rehabilitate his public image during his "Wilderness Years," the six-year

span between his failed run for the California governorship in 1962 and his

election as President in 1968.

14At the Court

chapter abstract

Against the backdrop of cultural concerns with privacy and press ethics,

and in the shadow of Sullivan and Griswold, Time, Inc. v. Hill came to the

Supreme Court freighted with a good deal of significance. The case tapped

into pressing social issues: the future of privacy in the information

society, the meaning of "the news," the boundaries of freedom of the press

in the age of big media. It also raised questions of constitutional

doctrine that were contested on the Court - the status of the

constitutional right to privacy, and possible extensions of the New York

Times v. Sullivan doctrine.

15Decisions

chapter abstract

After arguments by Nixon and Harold R. Medina, Jr., representing Time,

Inc., the Supreme Court initially came down on the side of privacy. A 6-3

majority decided in favor of the Hills, upholding the judgment of the New

York courts. Expanding the "right to privacy" established in the Griswold

decision, the majority opinion, written by Justice Abe Fortas, declared

that the Hills had a constitutional right to privacy that could be invoked

not only against the government, but also private actors like the press.

Ultimately, however, the Court changed its mind. As a result of lobbying by

Justice Hugo Black, a First Amendment absolutist, votes switched, and a new

majority voted in favor of Time, Inc.

16January 9, 1967

chapter abstract

William Brennan wrote the majority opinion in Time, Inc. v. Hill, issued in

January 1967. Invoking the New York Times v. Sullivan standard, Brennan

held that the Hills could not recover for invasion of privacy unless they

could show that Life's story about them was false, and that the falsehood

was made with reckless disregard of the truth. The Brennan opinion

announced a capacious vision of freedom of the press, perhaps the broadest

in the Supreme Court's history to that time.

17The Aftermath

chapter abstract

Time, Inc. v. Hill transformed the meaning of freedom of the press and the

scope of the right to privacy in the United States. Time, Inc. v. Hill set

forth an expansive vision of freedom of the press and dimmed the potential

for a strong right to privacy that could be invoked against the press. This

chapter examines the short and long-term consequences of the Hill decision

on politics, publishing, and the First Amendment.