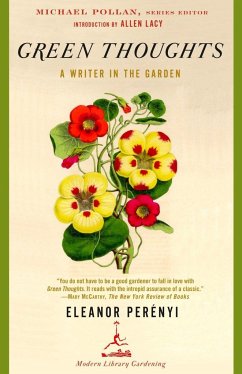

Onward and Upward in the Garden

PAYBACK Punkte

14 °P sammeln!

In 1925 Harold Ross hired Katharine Sergeant Angell as a manuscript reader for The New Yorker. Within months she became the magazine s first fiction editor, discovering and championing the work of Vladimir Nabokov, John Updike, James Thurber, Marianne Moore, and her husband-to-be, E. B. White, among others. After years of cultivating fiction, White set her sights on a new genre: garden writing. On March 1, 1958, The New Yorker ran a column entitled Onward and Upward in the Garden, a critical review of garden catalogs, in which White extolled the writings of seedmen and nurserymen, those unsung...

In 1925 Harold Ross hired Katharine Sergeant Angell as a manuscript reader for The New Yorker. Within months she became the magazine s first fiction editor, discovering and championing the work of Vladimir Nabokov, John Updike, James Thurber, Marianne Moore, and her husband-to-be, E. B. White, among others. After years of cultivating fiction, White set her sights on a new genre: garden writing. On March 1, 1958, The New Yorker ran a column entitled Onward and Upward in the Garden, a critical review of garden catalogs, in which White extolled the writings of seedmen and nurserymen, those unsung authors who produced her favorite reading matter. Thirteen more columns followed, exploring the history and literature of gardens, flower arranging, herbalists, and developments in gardening. Two years after her death in 1977, E. B. White collected and published the series, with a fond introduction. The result is this sharp-eyed appreciation of the green world of growing things, of the aesthetic pleasures of gardens and garden writing, and of the dreams that gardens inspire.

Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.