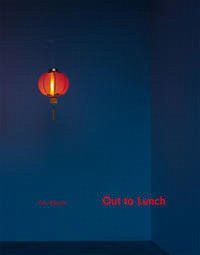

In ihrem Bildband "Out to Lunch" versammelt Ina Weber eine Reihe von keramischen Architekturskulpturen, die Varianten chinesischer Restaurants aus westlichen Breitengraden darstellen. Ina Weber beschäftigt sich mit der Faszination des Exotischen und seiner Romantisierung, mit den Tücken und Vergröberungen von Kulturtransfers. Die Keramikarbeiten verweisen in ihrer Thematik und Materialität auf die Chinoiserie des 18. Jahrhunderts und untersuchen gleichzeitig auch aktuellere populäre Formensprachen in der Architektur. Sie behandeln die gegenseitige Beeinflussung von Ost und West – zwischen Affirmation und Missverständnissen. Die Versatzstücke traditionellen chinesischen Bauens haben bei uns eine anhaltende Verbreitung gefunden, kommt doch keines der zahlreichen Chinarestaurants in jeder mittleren bis größeren Stadt ohne sie aus. Die Gaststätten waren zunächst ein urbanes Phänomen und galten europaweit als Ausdruck kultureller Modernität. Die Folklore fand erst im großen Boom der Chinarestaurants der 60er und 70er Jahre Einzug ins Ambiente. In dieser Zeit wuchs auch Ina Weber heran, und vielleicht eröffnete ja in frühester Kindheit ein erster Besuch in solch einem Etablissement im Kreise der Familie den Drang nach fernen und fremden Welten. Bis heute bezieht die Künstlerin einen Großteil ihrer Inspirationen von Reisen rund um den Globus.In her book “Out to Lunch,” Ina Weber assembles an array of ceramic architecture models depicting diverse variations of Chinese restaurants familiar to our hemisphere. Ina Weber concerns herself with the exotic and its romanticisation. Her ceramic works refer both to the subject matter and materiality of eighteenth-century chinoiserie and to contemporary trends in architecture. She deals with the mutual influence of east and west — between affirmation and misunderstanding. Certain elements of traditional Chinese building techniques have found a sustained and unbridled distribution in our hemisphere. In fact, not one of the many Chinese restaurants in any mid-sized or larger city could do without them. When the first restaurants run by Chinese owners opened in Berlin Charlottenburg in the 1920s, Asian folklore was by no means part of the décor. These restaurants were initially a decidedly urban phenomenon and were considered throughout Europe to be specific expressions of cultural modernity. It wasn’t until the big boom of Chinese restaurants in the ‘60s and ‘70s that folklore found its way into the ambience. It was during this time that Ina Weber was growing up, and perhaps it was one such early childhood visit in the circle of her family to a similar establishment that introduced the desire for far and unknown worlds. Even to this day, the artist draws much of her inspiration from traveling the globe.

Bitte wählen Sie Ihr Anliegen aus.

Rechnungen

Retourenschein anfordern

Bestellstatus

Storno