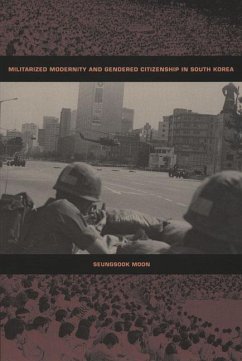

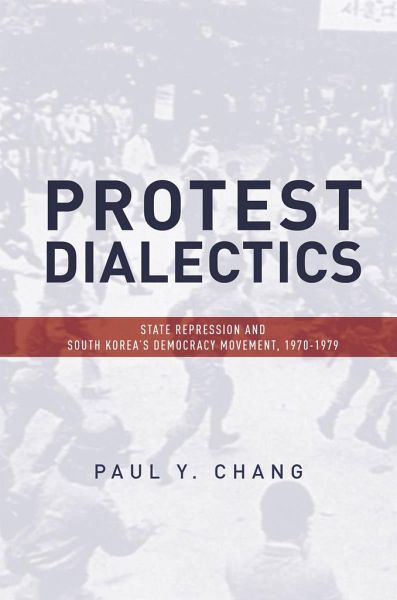

Protest Dialectics

State Repression and South Korea's Democracy Movement, 1970-1979

Versandkostenfrei!

Versandfertig in über 4 Wochen

128,99 €

inkl. MwSt.

Weitere Ausgaben:

PAYBACK Punkte

64 °P sammeln!

1970s South Korea is characterized by many as the "dark age for democracy." Most scholarship on South Korea's democracy movement and civil society has focused on the "student revolution" in 1960 and the large protest cycles in the 1980s which were followed by Korea's transition to democracy in 1987. But in his groundbreaking work of political and social history of 1970s South Korea, Paul Chang highlights the importance of understanding the emergence and evolution of the democracy movement in this oft-ignored decade. Protest Dialectics journeys back to 1970s South Korea and provides readers wit...

1970s South Korea is characterized by many as the "dark age for democracy." Most scholarship on South Korea's democracy movement and civil society has focused on the "student revolution" in 1960 and the large protest cycles in the 1980s which were followed by Korea's transition to democracy in 1987. But in his groundbreaking work of political and social history of 1970s South Korea, Paul Chang highlights the importance of understanding the emergence and evolution of the democracy movement in this oft-ignored decade. Protest Dialectics journeys back to 1970s South Korea and provides readers with an in-depth understanding of the numerous events in the 1970s that laid the groundwork for the 1980s democracy movement and the formation of civil society today. Chang shows how the narrative of the 1970s as democracy's "dark age" obfuscates the important material and discursive developments that became the foundations for the movement in the 1980s which, in turn, paved the way for the institutionalization of civil society after transition in 1987. To correct for these oversights in the literature and to better understand the origins of South Korea's vibrant social movement sector this book presents a comprehensive analysis of the emergence and evolution of the democracy movement in the 1970s.