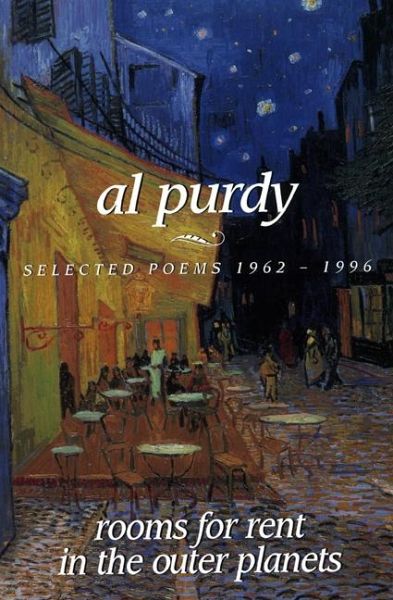

Al Purdy

Broschiertes Buch

Rooms for Rent in the Outer Planets: Selected Poems 1962-1996

Versandkostenfrei!

Nicht lieferbar

The definitive Al Purdy selected. Finalist for CBC Radio's Canada Reads 2006!

Save the Al Purdy A-Frame Campaign The Canadian League of Poets has declared a National Al Purdy Day! Al Purdy was born December 30, 1918, in Wooler, Ontario and died at Sidney, BC, April 21, 2000. Raised in Trenton, Ontario, he lived throughout Canada as he developed his reputation as one of Canada's greatest writers. His collections included two winners of the Governor General's Award, Cariboo Horses (1965) and Collected Poems (1986) and other classics such as Poems for All the Annettes, In Search of Owen Roblin and Piling Blood. Later in life, he travelled widely with his wife Eurithe and settled in Ameliasburg, Ontario and Sidney, BC. In addition to his thirty-three books of poetry, he published a novel, an autobiography and nine collections of essays and correspondence. He was appointed to the Order of Canada in 1983 and the Order of Ontario in 1987. His ashes are buried in Ameliasburg at the end of Purdy Lane.

Produktbeschreibung

- Verlag: Harbour Publishing Co. Ltd.

- UK

- Seitenzahl: 152

- Erscheinungstermin: Januar 1996

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 224mm x 152mm x 5mm

- Gewicht: 227g

- ISBN-13: 9781550171488

- ISBN-10: 1550171488

- Artikelnr.: 22128290

Herstellerkennzeichnung

Libri GmbH

Europaallee 1

36244 Bad Hersfeld

gpsr@libri.de

Für dieses Produkt wurde noch keine Bewertung abgegeben. Wir würden uns sehr freuen, wenn du die erste Bewertung schreibst!

Eine Bewertung schreiben

Eine Bewertung schreiben

Andere Kunden interessierten sich für