- Gebundenes Buch

- Merkliste

- Auf die Merkliste

- Bewerten Bewerten

- Teilen

- Produkt teilen

- Produkterinnerung

- Produkterinnerung

Evan Osborne is Professor of Economics at Wright State University. He is the author of Reasonably Simple Economics: Why the World Works the Way it Does (2013) and The Rise of the Anti-Corporate Movement: Corporations and the People Who Hate Them (2007).

Andere Kunden interessierten sich auch für

![Human Evolution, Economic Progress and Evolutionary Failure Human Evolution, Economic Progress and Evolutionary Failure]() Bhanoji RaoHuman Evolution, Economic Progress and Evolutionary Failure202,99 €

Bhanoji RaoHuman Evolution, Economic Progress and Evolutionary Failure202,99 €![Debt Sustainability of Subnational Governments in India Debt Sustainability of Subnational Governments in India]() Hari Krishna DwivediDebt Sustainability of Subnational Governments in India137,99 €

Hari Krishna DwivediDebt Sustainability of Subnational Governments in India137,99 €![The Gospel of Greed: Spirit of Commercialism the Vital Controlling Force in Human Affairs; Results in Progress for Humanity, Individualism The Gospel of Greed: Spirit of Commercialism the Vital Controlling Force in Human Affairs; Results in Progress for Humanity, Individualism]() Charles Hubert McDermottThe Gospel of Greed: Spirit of Commercialism the Vital Controlling Force in Human Affairs; Results in Progress for Humanity, Individualism37,99 €

Charles Hubert McDermottThe Gospel of Greed: Spirit of Commercialism the Vital Controlling Force in Human Affairs; Results in Progress for Humanity, Individualism37,99 €![Human Evolution, Economic Progress and Evolutionary Failure Human Evolution, Economic Progress and Evolutionary Failure]() Bhanoji RaoHuman Evolution, Economic Progress and Evolutionary Failure63,99 €

Bhanoji RaoHuman Evolution, Economic Progress and Evolutionary Failure63,99 €![Debow's Review: Agricultural, Commercial, Industrial Progress and Resources; Volume 11 Debow's Review: Agricultural, Commercial, Industrial Progress and Resources; Volume 11]() James Dunwoody Brownson De BowDebow's Review: Agricultural, Commercial, Industrial Progress and Resources; Volume 1150,99 €

James Dunwoody Brownson De BowDebow's Review: Agricultural, Commercial, Industrial Progress and Resources; Volume 1150,99 €![Making Policy Happen Making Policy Happen]() Leslie Budd / Julie Charlesworth / Rob Paton (eds.)Making Policy Happen264,99 €

Leslie Budd / Julie Charlesworth / Rob Paton (eds.)Making Policy Happen264,99 €![Organizational Behavior Organizational Behavior]() Meshack Mairura SaginiOrganizational Behavior220,99 €

Meshack Mairura SaginiOrganizational Behavior220,99 €-

-

Evan Osborne is Professor of Economics at Wright State University. He is the author of Reasonably Simple Economics: Why the World Works the Way it Does (2013) and The Rise of the Anti-Corporate Movement: Corporations and the People Who Hate Them (2007).

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Produktdetails

- Produktdetails

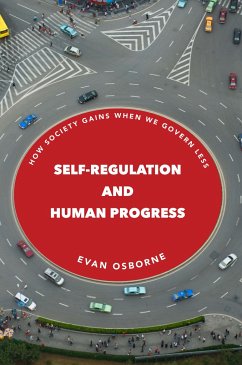

- Verlag: Stanford University Press

- Seitenzahl: 272

- Erscheinungstermin: 23. Januar 2018

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 231mm x 155mm x 23mm

- Gewicht: 612g

- ISBN-13: 9780804796446

- ISBN-10: 0804796440

- Artikelnr.: 47772015

- Herstellerkennzeichnung

- Libri GmbH

- Europaallee 1

- 36244 Bad Hersfeld

- gpsr@libri.de

- Verlag: Stanford University Press

- Seitenzahl: 272

- Erscheinungstermin: 23. Januar 2018

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 231mm x 155mm x 23mm

- Gewicht: 612g

- ISBN-13: 9780804796446

- ISBN-10: 0804796440

- Artikelnr.: 47772015

- Herstellerkennzeichnung

- Libri GmbH

- Europaallee 1

- 36244 Bad Hersfeld

- gpsr@libri.de

Evan Osborne is Professor of Economics at Wright State University. He is the author of Reasonably Simple Economics: Why the World Works the Way it Does (2013) and The Rise of the Anti-Corporate Movement: Corporations and the People Who Hate Them (2007).

Contents and Abstracts

1Problems and Responses

chapter abstract

Social systems can always function better than they do at a particular

moment. Whether there is a need to return to normal after an unexpected

disruption or to try to permanently improve the system's performance, there

is a never-ending set of problems to address. This book describes the

contrast between addressing such problems from outside that system through

politics and allowing the participants in that system to self-regulate

without external guidance of this kind. This chapter introduces this

problem and these two contrasting approaches to it, and defines some terms

that are frequently used in the book.

2Getting There: The Long Road to Self-Regulation

chapter abstract

Almost as long there has been a human species, we have formed societies

based on the principle of political regulation. There is a small cadre of

leaders often assumed to have the right to order the lives of other members

of society, supported by a current monopoly of armaments. While not

universal, this pattern has been the norm since the agricultural

revolution. In particular, it is argued that the idea of continuous social

improvement was hardly known in ancient civilizations. Only in the late

Renaissance did a pattern of thought evolve that indicated that it is

better to see the pattern and outcomes of human social systems as

progressing, with such systems capable under certain circumstances of

regulating themselves to better effect than outsiders could hope to

regulate them.

3Wrongs Make Rights: Self-Regulating Science

chapter abstract

Beginning in the 1600s, primarily in Britain, the Dutch Territories, and

France, people not only tried to think about how the world worked (a

pattern of thought as old as human civilization); they also agreed that

there was much that was yet unknown and collectively built procedures for

how to know more. The construction of the system for defining such

knowledge and evaluating claims to be adding to it has been a gradual

evolution that continues to this day. Among the landmark events discussed

are the development of the ideas of hypotheses, the experimental method,

free competition among scientific ideas, the use of the (growing number of)

mathematical tools to arbitrate scientific claims, the development of

modern research universities, the establishment and improvement of the peer

review system, and the more recent addition of techniques beyond

traditional scientific experiments as ways of supporting or falsifying

scientific claims.

4The Less Unsaid the Better: Self-Regulating Free Speech

chapter abstract

The question of how much free expression to tolerate hardly came up until

the modern era. The creation in Europe of the printing press changed that

and made expression a threat to long-standing social institutions. The

nature of the new technology made it impossible to fully control the flow

of books, pamphlets, and other printed material, but European governments

tried. The argument in favor of a free press ultimately emerged, and the

practice itself was institutionalized, mostly in Great Britain and

northwestern Europe. The chapter emphasizes the self-regulating argument

for free communication, that ideas beyond science would be improved if they

must be subject to readers' scrutiny. Particular attention is paid to

Milton, Struensee and John Stuart Mill. The arguments made in favor of the

broad protection of freedom of speech that prevail in much of the world are

shown to have significant self-regulating components.

5A Better Way Forward: Self-Regulating Socioeconomics

chapter abstract

There is a long history of condemning merchants as agents of social

disorder and little advocacy of free commerce as essential to ensure the

proper allocation of efforts across economic activities and promote

socioeconomic improvements. This began to change with both Aquinas and

thinkers in the late Renaissance in Spain asking different questions about

how producers could be induced to provide goods in a way that benefits

society. The contributions of Bernard Mandeville, Anne Robert Jacques

Turgot and, Adam Smith are sketched. By the end of the nineteenth century,

much of the general public and even political leaders in Europe and North

America believed in the virtues of the self-regulating socioeconomy.

Through colonialism and observation of the "modern" West's seemingly

obvious successes, people and societies around the world began in

ever-larger numbers to believe as well. But such widespread confidence was

not to last.

6Realignment: Fine Tuning in Light of Self-Regulation's Deficiencies

chapter abstract

The later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed arguments from

social reformers and artists and economists that the new, spontaneously

evolving society was deficient. It worsened poverty, and it impoverished

the soul. The tool of political regulation, exercised in the growing

political power of the emerging organization known as the nation, was

called in to polish the rough edges of the self-regulating society. As time

went on, political regulation gradually came to be seen as the default, and

self-regulation needed to be justified. The chapter particularly emphasizes

the growth in such thinking among socialists and progressives in the United

States and Western Europe. The catastrophe of the Great Depression,

combined with admiration for a Soviet Union, Italy, and Germany, where

political regulators said they were rationally designing a better society,

meant that by the onset of World War II, this presumption was firmly in

place throughout the West.

7Rebuilding: Systemic Changes to Counter Self-Regulation's Flaws

chapter abstract

Here the analysis turns to questioning the very premises that underlie the

virtues of self-regulating social systems. Macro-objections agree that

individuals cannot be assumed to be able to do what is best. It is the job

of political regulators to take over and facilitate the development of

society. Marxist theory in particular viewed history as unfolding

inevitably, and so appalling cruelties were inflicted by Marxist

governments to steer the revolution forward. The eugenics revolution

categorized entire groups of people as genetically inferior, frequently

because of their ethnicity. Politics was used in various countries to

improve society by reducing births among inferior types. Micro-objections

to self-regulation described individuals as incapable of being incented to

choose what self-regulation requires. In either case, it is the essential

task of political regulators to replace, if not destroy, the outcomes of

the choices made under self-regulation.

8Assessing the Decline of Confidence in Self-Regulation

chapter abstract

This chapter uses the new Google nGrams database to track the rise and fall

of different English-language phrases in order to illustrate the

corresponding rise and fall in confidence in self-regulation. After briefly

introducing evidence on the rise in the extent of political regulation over

the last century or so, documentation is presented on the parallel rise in

skepticism of the self-regulating socioeconomy and self-regulating science

generally, and in skepticism of the cognitive capacity of individuals to

make socially productive choices in particular.

9The Best Way(s) Forward

chapter abstract

There is good reason to be skeptical of the assumption that political

regulation operates with the public interest in mind. Scientific

productivity has continued to advance in the past half-century, as has the

value and quantity of human expression. The argument in favor of

socioeconomic self-regulation is identical to that for the other two

systems. Yet recent scholarship suggests declining rates of economic growth

in the wealthiest countries most subject to increasing political regulation

during this period, while greater reliance on self-regulating economic

forces has resulted in dramatic improvement of socioeconomies in the

developing world. As political regulation of human expression has declined,

literary, artistic, and philosophical achievement have expanded. Guidance

is offered for how people should understand social change in their role as

citizens and how they should conduct themselves in a world full of

short-term instability but tremendous long-term progress.

1Problems and Responses

chapter abstract

Social systems can always function better than they do at a particular

moment. Whether there is a need to return to normal after an unexpected

disruption or to try to permanently improve the system's performance, there

is a never-ending set of problems to address. This book describes the

contrast between addressing such problems from outside that system through

politics and allowing the participants in that system to self-regulate

without external guidance of this kind. This chapter introduces this

problem and these two contrasting approaches to it, and defines some terms

that are frequently used in the book.

2Getting There: The Long Road to Self-Regulation

chapter abstract

Almost as long there has been a human species, we have formed societies

based on the principle of political regulation. There is a small cadre of

leaders often assumed to have the right to order the lives of other members

of society, supported by a current monopoly of armaments. While not

universal, this pattern has been the norm since the agricultural

revolution. In particular, it is argued that the idea of continuous social

improvement was hardly known in ancient civilizations. Only in the late

Renaissance did a pattern of thought evolve that indicated that it is

better to see the pattern and outcomes of human social systems as

progressing, with such systems capable under certain circumstances of

regulating themselves to better effect than outsiders could hope to

regulate them.

3Wrongs Make Rights: Self-Regulating Science

chapter abstract

Beginning in the 1600s, primarily in Britain, the Dutch Territories, and

France, people not only tried to think about how the world worked (a

pattern of thought as old as human civilization); they also agreed that

there was much that was yet unknown and collectively built procedures for

how to know more. The construction of the system for defining such

knowledge and evaluating claims to be adding to it has been a gradual

evolution that continues to this day. Among the landmark events discussed

are the development of the ideas of hypotheses, the experimental method,

free competition among scientific ideas, the use of the (growing number of)

mathematical tools to arbitrate scientific claims, the development of

modern research universities, the establishment and improvement of the peer

review system, and the more recent addition of techniques beyond

traditional scientific experiments as ways of supporting or falsifying

scientific claims.

4The Less Unsaid the Better: Self-Regulating Free Speech

chapter abstract

The question of how much free expression to tolerate hardly came up until

the modern era. The creation in Europe of the printing press changed that

and made expression a threat to long-standing social institutions. The

nature of the new technology made it impossible to fully control the flow

of books, pamphlets, and other printed material, but European governments

tried. The argument in favor of a free press ultimately emerged, and the

practice itself was institutionalized, mostly in Great Britain and

northwestern Europe. The chapter emphasizes the self-regulating argument

for free communication, that ideas beyond science would be improved if they

must be subject to readers' scrutiny. Particular attention is paid to

Milton, Struensee and John Stuart Mill. The arguments made in favor of the

broad protection of freedom of speech that prevail in much of the world are

shown to have significant self-regulating components.

5A Better Way Forward: Self-Regulating Socioeconomics

chapter abstract

There is a long history of condemning merchants as agents of social

disorder and little advocacy of free commerce as essential to ensure the

proper allocation of efforts across economic activities and promote

socioeconomic improvements. This began to change with both Aquinas and

thinkers in the late Renaissance in Spain asking different questions about

how producers could be induced to provide goods in a way that benefits

society. The contributions of Bernard Mandeville, Anne Robert Jacques

Turgot and, Adam Smith are sketched. By the end of the nineteenth century,

much of the general public and even political leaders in Europe and North

America believed in the virtues of the self-regulating socioeconomy.

Through colonialism and observation of the "modern" West's seemingly

obvious successes, people and societies around the world began in

ever-larger numbers to believe as well. But such widespread confidence was

not to last.

6Realignment: Fine Tuning in Light of Self-Regulation's Deficiencies

chapter abstract

The later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed arguments from

social reformers and artists and economists that the new, spontaneously

evolving society was deficient. It worsened poverty, and it impoverished

the soul. The tool of political regulation, exercised in the growing

political power of the emerging organization known as the nation, was

called in to polish the rough edges of the self-regulating society. As time

went on, political regulation gradually came to be seen as the default, and

self-regulation needed to be justified. The chapter particularly emphasizes

the growth in such thinking among socialists and progressives in the United

States and Western Europe. The catastrophe of the Great Depression,

combined with admiration for a Soviet Union, Italy, and Germany, where

political regulators said they were rationally designing a better society,

meant that by the onset of World War II, this presumption was firmly in

place throughout the West.

7Rebuilding: Systemic Changes to Counter Self-Regulation's Flaws

chapter abstract

Here the analysis turns to questioning the very premises that underlie the

virtues of self-regulating social systems. Macro-objections agree that

individuals cannot be assumed to be able to do what is best. It is the job

of political regulators to take over and facilitate the development of

society. Marxist theory in particular viewed history as unfolding

inevitably, and so appalling cruelties were inflicted by Marxist

governments to steer the revolution forward. The eugenics revolution

categorized entire groups of people as genetically inferior, frequently

because of their ethnicity. Politics was used in various countries to

improve society by reducing births among inferior types. Micro-objections

to self-regulation described individuals as incapable of being incented to

choose what self-regulation requires. In either case, it is the essential

task of political regulators to replace, if not destroy, the outcomes of

the choices made under self-regulation.

8Assessing the Decline of Confidence in Self-Regulation

chapter abstract

This chapter uses the new Google nGrams database to track the rise and fall

of different English-language phrases in order to illustrate the

corresponding rise and fall in confidence in self-regulation. After briefly

introducing evidence on the rise in the extent of political regulation over

the last century or so, documentation is presented on the parallel rise in

skepticism of the self-regulating socioeconomy and self-regulating science

generally, and in skepticism of the cognitive capacity of individuals to

make socially productive choices in particular.

9The Best Way(s) Forward

chapter abstract

There is good reason to be skeptical of the assumption that political

regulation operates with the public interest in mind. Scientific

productivity has continued to advance in the past half-century, as has the

value and quantity of human expression. The argument in favor of

socioeconomic self-regulation is identical to that for the other two

systems. Yet recent scholarship suggests declining rates of economic growth

in the wealthiest countries most subject to increasing political regulation

during this period, while greater reliance on self-regulating economic

forces has resulted in dramatic improvement of socioeconomies in the

developing world. As political regulation of human expression has declined,

literary, artistic, and philosophical achievement have expanded. Guidance

is offered for how people should understand social change in their role as

citizens and how they should conduct themselves in a world full of

short-term instability but tremendous long-term progress.

Contents and Abstracts

1Problems and Responses

chapter abstract

Social systems can always function better than they do at a particular

moment. Whether there is a need to return to normal after an unexpected

disruption or to try to permanently improve the system's performance, there

is a never-ending set of problems to address. This book describes the

contrast between addressing such problems from outside that system through

politics and allowing the participants in that system to self-regulate

without external guidance of this kind. This chapter introduces this

problem and these two contrasting approaches to it, and defines some terms

that are frequently used in the book.

2Getting There: The Long Road to Self-Regulation

chapter abstract

Almost as long there has been a human species, we have formed societies

based on the principle of political regulation. There is a small cadre of

leaders often assumed to have the right to order the lives of other members

of society, supported by a current monopoly of armaments. While not

universal, this pattern has been the norm since the agricultural

revolution. In particular, it is argued that the idea of continuous social

improvement was hardly known in ancient civilizations. Only in the late

Renaissance did a pattern of thought evolve that indicated that it is

better to see the pattern and outcomes of human social systems as

progressing, with such systems capable under certain circumstances of

regulating themselves to better effect than outsiders could hope to

regulate them.

3Wrongs Make Rights: Self-Regulating Science

chapter abstract

Beginning in the 1600s, primarily in Britain, the Dutch Territories, and

France, people not only tried to think about how the world worked (a

pattern of thought as old as human civilization); they also agreed that

there was much that was yet unknown and collectively built procedures for

how to know more. The construction of the system for defining such

knowledge and evaluating claims to be adding to it has been a gradual

evolution that continues to this day. Among the landmark events discussed

are the development of the ideas of hypotheses, the experimental method,

free competition among scientific ideas, the use of the (growing number of)

mathematical tools to arbitrate scientific claims, the development of

modern research universities, the establishment and improvement of the peer

review system, and the more recent addition of techniques beyond

traditional scientific experiments as ways of supporting or falsifying

scientific claims.

4The Less Unsaid the Better: Self-Regulating Free Speech

chapter abstract

The question of how much free expression to tolerate hardly came up until

the modern era. The creation in Europe of the printing press changed that

and made expression a threat to long-standing social institutions. The

nature of the new technology made it impossible to fully control the flow

of books, pamphlets, and other printed material, but European governments

tried. The argument in favor of a free press ultimately emerged, and the

practice itself was institutionalized, mostly in Great Britain and

northwestern Europe. The chapter emphasizes the self-regulating argument

for free communication, that ideas beyond science would be improved if they

must be subject to readers' scrutiny. Particular attention is paid to

Milton, Struensee and John Stuart Mill. The arguments made in favor of the

broad protection of freedom of speech that prevail in much of the world are

shown to have significant self-regulating components.

5A Better Way Forward: Self-Regulating Socioeconomics

chapter abstract

There is a long history of condemning merchants as agents of social

disorder and little advocacy of free commerce as essential to ensure the

proper allocation of efforts across economic activities and promote

socioeconomic improvements. This began to change with both Aquinas and

thinkers in the late Renaissance in Spain asking different questions about

how producers could be induced to provide goods in a way that benefits

society. The contributions of Bernard Mandeville, Anne Robert Jacques

Turgot and, Adam Smith are sketched. By the end of the nineteenth century,

much of the general public and even political leaders in Europe and North

America believed in the virtues of the self-regulating socioeconomy.

Through colonialism and observation of the "modern" West's seemingly

obvious successes, people and societies around the world began in

ever-larger numbers to believe as well. But such widespread confidence was

not to last.

6Realignment: Fine Tuning in Light of Self-Regulation's Deficiencies

chapter abstract

The later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed arguments from

social reformers and artists and economists that the new, spontaneously

evolving society was deficient. It worsened poverty, and it impoverished

the soul. The tool of political regulation, exercised in the growing

political power of the emerging organization known as the nation, was

called in to polish the rough edges of the self-regulating society. As time

went on, political regulation gradually came to be seen as the default, and

self-regulation needed to be justified. The chapter particularly emphasizes

the growth in such thinking among socialists and progressives in the United

States and Western Europe. The catastrophe of the Great Depression,

combined with admiration for a Soviet Union, Italy, and Germany, where

political regulators said they were rationally designing a better society,

meant that by the onset of World War II, this presumption was firmly in

place throughout the West.

7Rebuilding: Systemic Changes to Counter Self-Regulation's Flaws

chapter abstract

Here the analysis turns to questioning the very premises that underlie the

virtues of self-regulating social systems. Macro-objections agree that

individuals cannot be assumed to be able to do what is best. It is the job

of political regulators to take over and facilitate the development of

society. Marxist theory in particular viewed history as unfolding

inevitably, and so appalling cruelties were inflicted by Marxist

governments to steer the revolution forward. The eugenics revolution

categorized entire groups of people as genetically inferior, frequently

because of their ethnicity. Politics was used in various countries to

improve society by reducing births among inferior types. Micro-objections

to self-regulation described individuals as incapable of being incented to

choose what self-regulation requires. In either case, it is the essential

task of political regulators to replace, if not destroy, the outcomes of

the choices made under self-regulation.

8Assessing the Decline of Confidence in Self-Regulation

chapter abstract

This chapter uses the new Google nGrams database to track the rise and fall

of different English-language phrases in order to illustrate the

corresponding rise and fall in confidence in self-regulation. After briefly

introducing evidence on the rise in the extent of political regulation over

the last century or so, documentation is presented on the parallel rise in

skepticism of the self-regulating socioeconomy and self-regulating science

generally, and in skepticism of the cognitive capacity of individuals to

make socially productive choices in particular.

9The Best Way(s) Forward

chapter abstract

There is good reason to be skeptical of the assumption that political

regulation operates with the public interest in mind. Scientific

productivity has continued to advance in the past half-century, as has the

value and quantity of human expression. The argument in favor of

socioeconomic self-regulation is identical to that for the other two

systems. Yet recent scholarship suggests declining rates of economic growth

in the wealthiest countries most subject to increasing political regulation

during this period, while greater reliance on self-regulating economic

forces has resulted in dramatic improvement of socioeconomies in the

developing world. As political regulation of human expression has declined,

literary, artistic, and philosophical achievement have expanded. Guidance

is offered for how people should understand social change in their role as

citizens and how they should conduct themselves in a world full of

short-term instability but tremendous long-term progress.

1Problems and Responses

chapter abstract

Social systems can always function better than they do at a particular

moment. Whether there is a need to return to normal after an unexpected

disruption or to try to permanently improve the system's performance, there

is a never-ending set of problems to address. This book describes the

contrast between addressing such problems from outside that system through

politics and allowing the participants in that system to self-regulate

without external guidance of this kind. This chapter introduces this

problem and these two contrasting approaches to it, and defines some terms

that are frequently used in the book.

2Getting There: The Long Road to Self-Regulation

chapter abstract

Almost as long there has been a human species, we have formed societies

based on the principle of political regulation. There is a small cadre of

leaders often assumed to have the right to order the lives of other members

of society, supported by a current monopoly of armaments. While not

universal, this pattern has been the norm since the agricultural

revolution. In particular, it is argued that the idea of continuous social

improvement was hardly known in ancient civilizations. Only in the late

Renaissance did a pattern of thought evolve that indicated that it is

better to see the pattern and outcomes of human social systems as

progressing, with such systems capable under certain circumstances of

regulating themselves to better effect than outsiders could hope to

regulate them.

3Wrongs Make Rights: Self-Regulating Science

chapter abstract

Beginning in the 1600s, primarily in Britain, the Dutch Territories, and

France, people not only tried to think about how the world worked (a

pattern of thought as old as human civilization); they also agreed that

there was much that was yet unknown and collectively built procedures for

how to know more. The construction of the system for defining such

knowledge and evaluating claims to be adding to it has been a gradual

evolution that continues to this day. Among the landmark events discussed

are the development of the ideas of hypotheses, the experimental method,

free competition among scientific ideas, the use of the (growing number of)

mathematical tools to arbitrate scientific claims, the development of

modern research universities, the establishment and improvement of the peer

review system, and the more recent addition of techniques beyond

traditional scientific experiments as ways of supporting or falsifying

scientific claims.

4The Less Unsaid the Better: Self-Regulating Free Speech

chapter abstract

The question of how much free expression to tolerate hardly came up until

the modern era. The creation in Europe of the printing press changed that

and made expression a threat to long-standing social institutions. The

nature of the new technology made it impossible to fully control the flow

of books, pamphlets, and other printed material, but European governments

tried. The argument in favor of a free press ultimately emerged, and the

practice itself was institutionalized, mostly in Great Britain and

northwestern Europe. The chapter emphasizes the self-regulating argument

for free communication, that ideas beyond science would be improved if they

must be subject to readers' scrutiny. Particular attention is paid to

Milton, Struensee and John Stuart Mill. The arguments made in favor of the

broad protection of freedom of speech that prevail in much of the world are

shown to have significant self-regulating components.

5A Better Way Forward: Self-Regulating Socioeconomics

chapter abstract

There is a long history of condemning merchants as agents of social

disorder and little advocacy of free commerce as essential to ensure the

proper allocation of efforts across economic activities and promote

socioeconomic improvements. This began to change with both Aquinas and

thinkers in the late Renaissance in Spain asking different questions about

how producers could be induced to provide goods in a way that benefits

society. The contributions of Bernard Mandeville, Anne Robert Jacques

Turgot and, Adam Smith are sketched. By the end of the nineteenth century,

much of the general public and even political leaders in Europe and North

America believed in the virtues of the self-regulating socioeconomy.

Through colonialism and observation of the "modern" West's seemingly

obvious successes, people and societies around the world began in

ever-larger numbers to believe as well. But such widespread confidence was

not to last.

6Realignment: Fine Tuning in Light of Self-Regulation's Deficiencies

chapter abstract

The later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed arguments from

social reformers and artists and economists that the new, spontaneously

evolving society was deficient. It worsened poverty, and it impoverished

the soul. The tool of political regulation, exercised in the growing

political power of the emerging organization known as the nation, was

called in to polish the rough edges of the self-regulating society. As time

went on, political regulation gradually came to be seen as the default, and

self-regulation needed to be justified. The chapter particularly emphasizes

the growth in such thinking among socialists and progressives in the United

States and Western Europe. The catastrophe of the Great Depression,

combined with admiration for a Soviet Union, Italy, and Germany, where

political regulators said they were rationally designing a better society,

meant that by the onset of World War II, this presumption was firmly in

place throughout the West.

7Rebuilding: Systemic Changes to Counter Self-Regulation's Flaws

chapter abstract

Here the analysis turns to questioning the very premises that underlie the

virtues of self-regulating social systems. Macro-objections agree that

individuals cannot be assumed to be able to do what is best. It is the job

of political regulators to take over and facilitate the development of

society. Marxist theory in particular viewed history as unfolding

inevitably, and so appalling cruelties were inflicted by Marxist

governments to steer the revolution forward. The eugenics revolution

categorized entire groups of people as genetically inferior, frequently

because of their ethnicity. Politics was used in various countries to

improve society by reducing births among inferior types. Micro-objections

to self-regulation described individuals as incapable of being incented to

choose what self-regulation requires. In either case, it is the essential

task of political regulators to replace, if not destroy, the outcomes of

the choices made under self-regulation.

8Assessing the Decline of Confidence in Self-Regulation

chapter abstract

This chapter uses the new Google nGrams database to track the rise and fall

of different English-language phrases in order to illustrate the

corresponding rise and fall in confidence in self-regulation. After briefly

introducing evidence on the rise in the extent of political regulation over

the last century or so, documentation is presented on the parallel rise in

skepticism of the self-regulating socioeconomy and self-regulating science

generally, and in skepticism of the cognitive capacity of individuals to

make socially productive choices in particular.

9The Best Way(s) Forward

chapter abstract

There is good reason to be skeptical of the assumption that political

regulation operates with the public interest in mind. Scientific

productivity has continued to advance in the past half-century, as has the

value and quantity of human expression. The argument in favor of

socioeconomic self-regulation is identical to that for the other two

systems. Yet recent scholarship suggests declining rates of economic growth

in the wealthiest countries most subject to increasing political regulation

during this period, while greater reliance on self-regulating economic

forces has resulted in dramatic improvement of socioeconomies in the

developing world. As political regulation of human expression has declined,

literary, artistic, and philosophical achievement have expanded. Guidance

is offered for how people should understand social change in their role as

citizens and how they should conduct themselves in a world full of

short-term instability but tremendous long-term progress.