Christopher Loperena

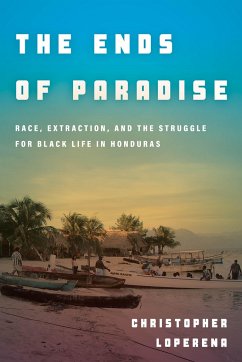

The Ends of Paradise

Race, Extraction, and the Struggle for Black Life in Honduras

Christopher Loperena

The Ends of Paradise

Race, Extraction, and the Struggle for Black Life in Honduras

- Gebundenes Buch

- Merkliste

- Auf die Merkliste

- Bewerten Bewerten

- Teilen

- Produkt teilen

- Produkterinnerung

- Produkterinnerung

"The future of Honduras begins and ends on the white sand beaches of Tela Bay on the country's northeastern coast where Garifuna, a Black Indigenous people, have resided for over 200 years. In "The Ends of Paradise," Christopher Loperena examines the Garifuna struggle for life and collective autonomy, and demonstrates how this struggle challenges concerted efforts by the state and multilateral institutions, such as the World Bank, to render both their lands and their culture into fungible tourism products. Using a combination of participant observation, courtroom ethnography, and archival…mehr

Andere Kunden interessierten sich auch für

![The Ends of Paradise The Ends of Paradise]() Christopher LoperenaThe Ends of Paradise28,99 €

Christopher LoperenaThe Ends of Paradise28,99 €![The Strange Career of Racial Liberalism The Strange Career of Racial Liberalism]() Joseph DardaThe Strange Career of Racial Liberalism26,99 €

Joseph DardaThe Strange Career of Racial Liberalism26,99 €![The News at the Ends of the Earth The News at the Ends of the Earth]() Hester BlumThe News at the Ends of the Earth38,99 €

Hester BlumThe News at the Ends of the Earth38,99 €![Reworking Citizenship Reworking Citizenship]() Brady G'sellReworking Citizenship34,99 €

Brady G'sellReworking Citizenship34,99 €![Heritage and the Cultural Struggle for Palestine Heritage and the Cultural Struggle for Palestine]() Chiara De CesariHeritage and the Cultural Struggle for Palestine125,99 €

Chiara De CesariHeritage and the Cultural Struggle for Palestine125,99 €![The Souls of White Jokes The Souls of White Jokes]() Raul PerezThe Souls of White Jokes20,99 €

Raul PerezThe Souls of White Jokes20,99 €![The Inconvenient Generation The Inconvenient Generation]() Minhua LingThe Inconvenient Generation125,99 €

Minhua LingThe Inconvenient Generation125,99 €-

-

-

"The future of Honduras begins and ends on the white sand beaches of Tela Bay on the country's northeastern coast where Garifuna, a Black Indigenous people, have resided for over 200 years. In "The Ends of Paradise," Christopher Loperena examines the Garifuna struggle for life and collective autonomy, and demonstrates how this struggle challenges concerted efforts by the state and multilateral institutions, such as the World Bank, to render both their lands and their culture into fungible tourism products. Using a combination of participant observation, courtroom ethnography, and archival research, Loperena reveals how purportedly inclusive tourism projects form part of a larger neoliberal, extractivist development regime, which remakes Black and Indigenous territories into frontiers of progress for the mestizo majority. The book offers a trenchant analysis of the ways Black dispossession and displacement are carried forth through the conferral of individual rights and freedoms, a prerequisite for resource exploitation under contemporary capitalism. By demanding to be accounted for on their terms, Garifuna anchor blackness to Central America--a place where Black peoples are presumed to be nonnative inhabitants--and to collective land rights. Steeped in Loperena's long term activist engagement with Garifuna land defenders, this book is a testament to their struggle and to the promise of "another world" in which Black and Indigenous peoples thrive"--

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Produktdetails

- Produktdetails

- Verlag: Stanford University Press

- Seitenzahl: 232

- Erscheinungstermin: 15. November 2022

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 231mm x 150mm x 20mm

- Gewicht: 498g

- ISBN-13: 9781503632950

- ISBN-10: 1503632954

- Artikelnr.: 63936087

- Herstellerkennzeichnung

- Libri GmbH

- Europaallee 1

- 36244 Bad Hersfeld

- gpsr@libri.de

- Verlag: Stanford University Press

- Seitenzahl: 232

- Erscheinungstermin: 15. November 2022

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 231mm x 150mm x 20mm

- Gewicht: 498g

- ISBN-13: 9781503632950

- ISBN-10: 1503632954

- Artikelnr.: 63936087

- Herstellerkennzeichnung

- Libri GmbH

- Europaallee 1

- 36244 Bad Hersfeld

- gpsr@libri.de

Christopher A. Loperena is Associate Professor of Anthropology at the Graduate Center, City University of New York.

Contents and Abstracts

Introduction: Imagining Black Indigenous Futures

chapter abstract

The introduction establishes how Black and Indigenous struggles for

territorial autonomy in Honduras interact with larger social and economic

forces, including the global resurgence of resource extraction that is

slowly eroding the customary rights of Indigenous peoples across the

Americas. Although the government of Honduras has presented tourism as a

sustainable alternative to extractive industries, this chapter argues that

tourism is an extractivist enterprise premised on environmental

dispossession and racial violence against rural communities of color. It

also shows how Garifuna-a Black Indigenous people of African, Arawak, and

Carib descent-fight back against the extractivist mandate of the Honduran

state and multinational capital on the Caribbean Coast.

1The Extractivist Logics of Progress

chapter abstract

Chapter 1 traces the historical genealogy of extractivism in Honduras. From

the banana enclaves of the early twentieth century to sumptuous coastal

tourism resorts and the contemporary bid to establish semiautonomous

charter cities in purportedly unpopulated areas of the country, the state

has tried to enact various visions of progress. All these visions, though,

are intimately tethered to extractivism, particularly racial extractivism.

2The Garifuna Coast: The Inclusionary Politics of Expulsion

chapter abstract

Chapter 2 analyzes how the tourism economy facilitates racialized

extraction. The advent of multicultural rights unfolded alongside state

programs designed to transform Garifuna people into subjects of

development. But the inclusion of Black and Indigenous communities seems

inseparable from the commodification of those communities; the government's

policies all seem to render Garifuna lands and culture as tourism products.

These policies are presented as a win-win for everyone, equally beneficial

to Garifuna and working-class non-Indigenous Hondurans who remain stymied

by poverty and the legacy of "underdevelopment." The only clear winner is

not either one of these groups, but rather the mestizo elite. Garifuna

resistance to government policies exposes the inner workings of supposedly

inclusionary politics and how those efforts ultimately advance not

inclusion, but racial and spatial expulsion.

3Tensions of Autonomous Blackness

chapter abstract

Chapter 3 examines how statist development objectives seep into the lives

of Garifuna in Triunfo de la Cruz, Honduras. Neoliberal economic paradigms

emerged in tandem with morally saturated development discourses that tout

poverty reduction, inclusion, and sustainability, and also imagine Garifuna

as stakeholders with the capacity to benefit from and contribute

productively to Honduras's tourism economy. Policies that promote

participation in the tourism economy are entangled with contests over land

and belonging. Conflicts over the fate of the community figure prominently

in daily life, as community members-for and against government-sponsored

development-reckon with the dispossession that inevitably come with

development and debate how to negotiate with and when to protest against

these forces. Garifuna land defense strategies are articulated through the

practice of Black autonomy: an ethico-political proposal that refuses

dominant narratives of progress and instead asserts a notion of autonomy as

collective action and social good.

4Rescue the Land, Defend the Future

chapter abstract

Chapter 4 theorizes the spatial and temporal dimensions of Garifuna

political subjectivity through an analysis of the movement to recuperate or

"rescue" communal lands from privatization. The chapter examines how

Garifuna women lead the lucha (struggle) in defense of their territory with

their bodies, and how that defense is bound up with gendered narratives of

ancestrality and the praxis of territorial mothering. To live ancestrally

is a way of being in relation with the land, which is crucial to Garifuna

autonomy and a key feature of the struggle to contest the

destination-making strategies of multinational capital on the Caribbean

coast.

5The Limits of Indigeneity: Pueblo Garifuna v. Honduras

chapter abstract

Chapter 5 examines the public hearing at the Inter-American Court of Human

Rights of the Garifuna Community Triunfo de la Cruz and Its Members v.

Honduras. During court proceedings, Honduras's deputy attorney general

argued that Garifuna should not be considered an "original people"

(indigenous to Honduras) and thus Garifuna claims to national territory

were not legitimate. State officials not only undermined the possibility of

Black Indigeneity but also exalted the rights of officially recognized

Indigenous peoples to defend mestizo property rights in the zone. This

politics of (mis)recognition tethers Indigenous subjectivity to the mestizo

nation-building project and ideologies of whitening. It reinforces the

perception that Black people are foreigners in Honduras. The court's

judgment in favor of the community established an important legal precedent

for the recognition of Black territorial rights but also served to buttress

state sovereignty over natural resources deemed to be of "public use."

Conclusion: Conclusion

chapter abstract

The conclusion to this book begins with the violent murder of the

Indigenous activist Berta Cáceres. At the time of her death, Cáceres was

leading a daring community uprising against the development of a large

hydroelectric project slated to be built on the Gualcarque River in the

Lenca community of Río Blanco. Her death marked the beginning of a new wave

of repression against Indigenous and Black activists that reached its apex

on July 18, 2020, with the kidnapping of four community leaders in Triunfo

de la Cruz. This worrisome pattern demonstrates deep-seated racial animus

toward Black and Indigenous peoples and the rights they fought so hard to

obtain during the preceding decades. In spite of the devastating and racist

violence they face, Black and Indigenous peoples continue to mobilize in

defense of life.

chapter abstract

Introduction: Imagining Black Indigenous Futures

chapter abstract

The introduction establishes how Black and Indigenous struggles for

territorial autonomy in Honduras interact with larger social and economic

forces, including the global resurgence of resource extraction that is

slowly eroding the customary rights of Indigenous peoples across the

Americas. Although the government of Honduras has presented tourism as a

sustainable alternative to extractive industries, this chapter argues that

tourism is an extractivist enterprise premised on environmental

dispossession and racial violence against rural communities of color. It

also shows how Garifuna-a Black Indigenous people of African, Arawak, and

Carib descent-fight back against the extractivist mandate of the Honduran

state and multinational capital on the Caribbean Coast.

1The Extractivist Logics of Progress

chapter abstract

Chapter 1 traces the historical genealogy of extractivism in Honduras. From

the banana enclaves of the early twentieth century to sumptuous coastal

tourism resorts and the contemporary bid to establish semiautonomous

charter cities in purportedly unpopulated areas of the country, the state

has tried to enact various visions of progress. All these visions, though,

are intimately tethered to extractivism, particularly racial extractivism.

2The Garifuna Coast: The Inclusionary Politics of Expulsion

chapter abstract

Chapter 2 analyzes how the tourism economy facilitates racialized

extraction. The advent of multicultural rights unfolded alongside state

programs designed to transform Garifuna people into subjects of

development. But the inclusion of Black and Indigenous communities seems

inseparable from the commodification of those communities; the government's

policies all seem to render Garifuna lands and culture as tourism products.

These policies are presented as a win-win for everyone, equally beneficial

to Garifuna and working-class non-Indigenous Hondurans who remain stymied

by poverty and the legacy of "underdevelopment." The only clear winner is

not either one of these groups, but rather the mestizo elite. Garifuna

resistance to government policies exposes the inner workings of supposedly

inclusionary politics and how those efforts ultimately advance not

inclusion, but racial and spatial expulsion.

3Tensions of Autonomous Blackness

chapter abstract

Chapter 3 examines how statist development objectives seep into the lives

of Garifuna in Triunfo de la Cruz, Honduras. Neoliberal economic paradigms

emerged in tandem with morally saturated development discourses that tout

poverty reduction, inclusion, and sustainability, and also imagine Garifuna

as stakeholders with the capacity to benefit from and contribute

productively to Honduras's tourism economy. Policies that promote

participation in the tourism economy are entangled with contests over land

and belonging. Conflicts over the fate of the community figure prominently

in daily life, as community members-for and against government-sponsored

development-reckon with the dispossession that inevitably come with

development and debate how to negotiate with and when to protest against

these forces. Garifuna land defense strategies are articulated through the

practice of Black autonomy: an ethico-political proposal that refuses

dominant narratives of progress and instead asserts a notion of autonomy as

collective action and social good.

4Rescue the Land, Defend the Future

chapter abstract

Chapter 4 theorizes the spatial and temporal dimensions of Garifuna

political subjectivity through an analysis of the movement to recuperate or

"rescue" communal lands from privatization. The chapter examines how

Garifuna women lead the lucha (struggle) in defense of their territory with

their bodies, and how that defense is bound up with gendered narratives of

ancestrality and the praxis of territorial mothering. To live ancestrally

is a way of being in relation with the land, which is crucial to Garifuna

autonomy and a key feature of the struggle to contest the

destination-making strategies of multinational capital on the Caribbean

coast.

5The Limits of Indigeneity: Pueblo Garifuna v. Honduras

chapter abstract

Chapter 5 examines the public hearing at the Inter-American Court of Human

Rights of the Garifuna Community Triunfo de la Cruz and Its Members v.

Honduras. During court proceedings, Honduras's deputy attorney general

argued that Garifuna should not be considered an "original people"

(indigenous to Honduras) and thus Garifuna claims to national territory

were not legitimate. State officials not only undermined the possibility of

Black Indigeneity but also exalted the rights of officially recognized

Indigenous peoples to defend mestizo property rights in the zone. This

politics of (mis)recognition tethers Indigenous subjectivity to the mestizo

nation-building project and ideologies of whitening. It reinforces the

perception that Black people are foreigners in Honduras. The court's

judgment in favor of the community established an important legal precedent

for the recognition of Black territorial rights but also served to buttress

state sovereignty over natural resources deemed to be of "public use."

Conclusion: Conclusion

chapter abstract

The conclusion to this book begins with the violent murder of the

Indigenous activist Berta Cáceres. At the time of her death, Cáceres was

leading a daring community uprising against the development of a large

hydroelectric project slated to be built on the Gualcarque River in the

Lenca community of Río Blanco. Her death marked the beginning of a new wave

of repression against Indigenous and Black activists that reached its apex

on July 18, 2020, with the kidnapping of four community leaders in Triunfo

de la Cruz. This worrisome pattern demonstrates deep-seated racial animus

toward Black and Indigenous peoples and the rights they fought so hard to

obtain during the preceding decades. In spite of the devastating and racist

violence they face, Black and Indigenous peoples continue to mobilize in

defense of life.

chapter abstract

Contents and Abstracts

Introduction: Imagining Black Indigenous Futures

chapter abstract

The introduction establishes how Black and Indigenous struggles for

territorial autonomy in Honduras interact with larger social and economic

forces, including the global resurgence of resource extraction that is

slowly eroding the customary rights of Indigenous peoples across the

Americas. Although the government of Honduras has presented tourism as a

sustainable alternative to extractive industries, this chapter argues that

tourism is an extractivist enterprise premised on environmental

dispossession and racial violence against rural communities of color. It

also shows how Garifuna-a Black Indigenous people of African, Arawak, and

Carib descent-fight back against the extractivist mandate of the Honduran

state and multinational capital on the Caribbean Coast.

1The Extractivist Logics of Progress

chapter abstract

Chapter 1 traces the historical genealogy of extractivism in Honduras. From

the banana enclaves of the early twentieth century to sumptuous coastal

tourism resorts and the contemporary bid to establish semiautonomous

charter cities in purportedly unpopulated areas of the country, the state

has tried to enact various visions of progress. All these visions, though,

are intimately tethered to extractivism, particularly racial extractivism.

2The Garifuna Coast: The Inclusionary Politics of Expulsion

chapter abstract

Chapter 2 analyzes how the tourism economy facilitates racialized

extraction. The advent of multicultural rights unfolded alongside state

programs designed to transform Garifuna people into subjects of

development. But the inclusion of Black and Indigenous communities seems

inseparable from the commodification of those communities; the government's

policies all seem to render Garifuna lands and culture as tourism products.

These policies are presented as a win-win for everyone, equally beneficial

to Garifuna and working-class non-Indigenous Hondurans who remain stymied

by poverty and the legacy of "underdevelopment." The only clear winner is

not either one of these groups, but rather the mestizo elite. Garifuna

resistance to government policies exposes the inner workings of supposedly

inclusionary politics and how those efforts ultimately advance not

inclusion, but racial and spatial expulsion.

3Tensions of Autonomous Blackness

chapter abstract

Chapter 3 examines how statist development objectives seep into the lives

of Garifuna in Triunfo de la Cruz, Honduras. Neoliberal economic paradigms

emerged in tandem with morally saturated development discourses that tout

poverty reduction, inclusion, and sustainability, and also imagine Garifuna

as stakeholders with the capacity to benefit from and contribute

productively to Honduras's tourism economy. Policies that promote

participation in the tourism economy are entangled with contests over land

and belonging. Conflicts over the fate of the community figure prominently

in daily life, as community members-for and against government-sponsored

development-reckon with the dispossession that inevitably come with

development and debate how to negotiate with and when to protest against

these forces. Garifuna land defense strategies are articulated through the

practice of Black autonomy: an ethico-political proposal that refuses

dominant narratives of progress and instead asserts a notion of autonomy as

collective action and social good.

4Rescue the Land, Defend the Future

chapter abstract

Chapter 4 theorizes the spatial and temporal dimensions of Garifuna

political subjectivity through an analysis of the movement to recuperate or

"rescue" communal lands from privatization. The chapter examines how

Garifuna women lead the lucha (struggle) in defense of their territory with

their bodies, and how that defense is bound up with gendered narratives of

ancestrality and the praxis of territorial mothering. To live ancestrally

is a way of being in relation with the land, which is crucial to Garifuna

autonomy and a key feature of the struggle to contest the

destination-making strategies of multinational capital on the Caribbean

coast.

5The Limits of Indigeneity: Pueblo Garifuna v. Honduras

chapter abstract

Chapter 5 examines the public hearing at the Inter-American Court of Human

Rights of the Garifuna Community Triunfo de la Cruz and Its Members v.

Honduras. During court proceedings, Honduras's deputy attorney general

argued that Garifuna should not be considered an "original people"

(indigenous to Honduras) and thus Garifuna claims to national territory

were not legitimate. State officials not only undermined the possibility of

Black Indigeneity but also exalted the rights of officially recognized

Indigenous peoples to defend mestizo property rights in the zone. This

politics of (mis)recognition tethers Indigenous subjectivity to the mestizo

nation-building project and ideologies of whitening. It reinforces the

perception that Black people are foreigners in Honduras. The court's

judgment in favor of the community established an important legal precedent

for the recognition of Black territorial rights but also served to buttress

state sovereignty over natural resources deemed to be of "public use."

Conclusion: Conclusion

chapter abstract

The conclusion to this book begins with the violent murder of the

Indigenous activist Berta Cáceres. At the time of her death, Cáceres was

leading a daring community uprising against the development of a large

hydroelectric project slated to be built on the Gualcarque River in the

Lenca community of Río Blanco. Her death marked the beginning of a new wave

of repression against Indigenous and Black activists that reached its apex

on July 18, 2020, with the kidnapping of four community leaders in Triunfo

de la Cruz. This worrisome pattern demonstrates deep-seated racial animus

toward Black and Indigenous peoples and the rights they fought so hard to

obtain during the preceding decades. In spite of the devastating and racist

violence they face, Black and Indigenous peoples continue to mobilize in

defense of life.

chapter abstract

Introduction: Imagining Black Indigenous Futures

chapter abstract

The introduction establishes how Black and Indigenous struggles for

territorial autonomy in Honduras interact with larger social and economic

forces, including the global resurgence of resource extraction that is

slowly eroding the customary rights of Indigenous peoples across the

Americas. Although the government of Honduras has presented tourism as a

sustainable alternative to extractive industries, this chapter argues that

tourism is an extractivist enterprise premised on environmental

dispossession and racial violence against rural communities of color. It

also shows how Garifuna-a Black Indigenous people of African, Arawak, and

Carib descent-fight back against the extractivist mandate of the Honduran

state and multinational capital on the Caribbean Coast.

1The Extractivist Logics of Progress

chapter abstract

Chapter 1 traces the historical genealogy of extractivism in Honduras. From

the banana enclaves of the early twentieth century to sumptuous coastal

tourism resorts and the contemporary bid to establish semiautonomous

charter cities in purportedly unpopulated areas of the country, the state

has tried to enact various visions of progress. All these visions, though,

are intimately tethered to extractivism, particularly racial extractivism.

2The Garifuna Coast: The Inclusionary Politics of Expulsion

chapter abstract

Chapter 2 analyzes how the tourism economy facilitates racialized

extraction. The advent of multicultural rights unfolded alongside state

programs designed to transform Garifuna people into subjects of

development. But the inclusion of Black and Indigenous communities seems

inseparable from the commodification of those communities; the government's

policies all seem to render Garifuna lands and culture as tourism products.

These policies are presented as a win-win for everyone, equally beneficial

to Garifuna and working-class non-Indigenous Hondurans who remain stymied

by poverty and the legacy of "underdevelopment." The only clear winner is

not either one of these groups, but rather the mestizo elite. Garifuna

resistance to government policies exposes the inner workings of supposedly

inclusionary politics and how those efforts ultimately advance not

inclusion, but racial and spatial expulsion.

3Tensions of Autonomous Blackness

chapter abstract

Chapter 3 examines how statist development objectives seep into the lives

of Garifuna in Triunfo de la Cruz, Honduras. Neoliberal economic paradigms

emerged in tandem with morally saturated development discourses that tout

poverty reduction, inclusion, and sustainability, and also imagine Garifuna

as stakeholders with the capacity to benefit from and contribute

productively to Honduras's tourism economy. Policies that promote

participation in the tourism economy are entangled with contests over land

and belonging. Conflicts over the fate of the community figure prominently

in daily life, as community members-for and against government-sponsored

development-reckon with the dispossession that inevitably come with

development and debate how to negotiate with and when to protest against

these forces. Garifuna land defense strategies are articulated through the

practice of Black autonomy: an ethico-political proposal that refuses

dominant narratives of progress and instead asserts a notion of autonomy as

collective action and social good.

4Rescue the Land, Defend the Future

chapter abstract

Chapter 4 theorizes the spatial and temporal dimensions of Garifuna

political subjectivity through an analysis of the movement to recuperate or

"rescue" communal lands from privatization. The chapter examines how

Garifuna women lead the lucha (struggle) in defense of their territory with

their bodies, and how that defense is bound up with gendered narratives of

ancestrality and the praxis of territorial mothering. To live ancestrally

is a way of being in relation with the land, which is crucial to Garifuna

autonomy and a key feature of the struggle to contest the

destination-making strategies of multinational capital on the Caribbean

coast.

5The Limits of Indigeneity: Pueblo Garifuna v. Honduras

chapter abstract

Chapter 5 examines the public hearing at the Inter-American Court of Human

Rights of the Garifuna Community Triunfo de la Cruz and Its Members v.

Honduras. During court proceedings, Honduras's deputy attorney general

argued that Garifuna should not be considered an "original people"

(indigenous to Honduras) and thus Garifuna claims to national territory

were not legitimate. State officials not only undermined the possibility of

Black Indigeneity but also exalted the rights of officially recognized

Indigenous peoples to defend mestizo property rights in the zone. This

politics of (mis)recognition tethers Indigenous subjectivity to the mestizo

nation-building project and ideologies of whitening. It reinforces the

perception that Black people are foreigners in Honduras. The court's

judgment in favor of the community established an important legal precedent

for the recognition of Black territorial rights but also served to buttress

state sovereignty over natural resources deemed to be of "public use."

Conclusion: Conclusion

chapter abstract

The conclusion to this book begins with the violent murder of the

Indigenous activist Berta Cáceres. At the time of her death, Cáceres was

leading a daring community uprising against the development of a large

hydroelectric project slated to be built on the Gualcarque River in the

Lenca community of Río Blanco. Her death marked the beginning of a new wave

of repression against Indigenous and Black activists that reached its apex

on July 18, 2020, with the kidnapping of four community leaders in Triunfo

de la Cruz. This worrisome pattern demonstrates deep-seated racial animus

toward Black and Indigenous peoples and the rights they fought so hard to

obtain during the preceding decades. In spite of the devastating and racist

violence they face, Black and Indigenous peoples continue to mobilize in

defense of life.

chapter abstract