Nicht lieferbar

The Lamentations of Julius Marantz

Versandkostenfrei!

Nicht lieferbar

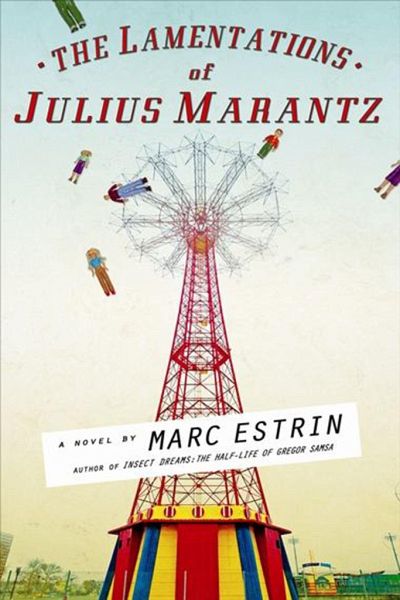

Who would benefit if they really did bring The Rapture on?Marc Estrin follows another of his strange protagonists through a world troubled by what it knows and by how it applies that knowledge.From the first page, we are plunged into a global riot of paranoia, joy, and fear. But something is sadly familiar here, perhaps because we have been taught to anticipate a world in which people suddenly fly off the planet. It might be The Rapture. Or it might be some violation of the force of gravity. Whatever it is, it's spreading madness, religious hysteria, and some truly formidable government powers...

Who would benefit if they really did bring The Rapture on?

Marc Estrin follows another of his strange protagonists through a world troubled by what it knows and by how it applies that knowledge.

From the first page, we are plunged into a global riot of paranoia, joy, and fear. But something is sadly familiar here, perhaps because we have been taught to anticipate a world in which people suddenly fly off the planet. It might be The Rapture. Or it might be some violation of the force of gravity. Whatever it is, it's spreading madness, religious hysteria, and some truly formidable government powers.

The voice of these Lamentations is a sixty-something, club-footed scientist named Julius Marantz, an obsessive researcher who suffers both from forbidden knowledge and an insistent conscience. As his spirit and his heart begin to fail, Julius realizes what is lost to him: a childhood of possibility, the consolation of belief, and the undying optimism of a father who taught him the principles of physics on the roller-coaster and the parachute jump.

Partly a portrait of cynical politics and religious fervor, part scientific speculation and even a meditation on the glories of Coney Island, The Lamentations of Julius Marantz traces the rise and fall of science in a truly personal story that finally fairly ascends.

Marc Estrin follows another of his strange protagonists through a world troubled by what it knows and by how it applies that knowledge.

From the first page, we are plunged into a global riot of paranoia, joy, and fear. But something is sadly familiar here, perhaps because we have been taught to anticipate a world in which people suddenly fly off the planet. It might be The Rapture. Or it might be some violation of the force of gravity. Whatever it is, it's spreading madness, religious hysteria, and some truly formidable government powers.

The voice of these Lamentations is a sixty-something, club-footed scientist named Julius Marantz, an obsessive researcher who suffers both from forbidden knowledge and an insistent conscience. As his spirit and his heart begin to fail, Julius realizes what is lost to him: a childhood of possibility, the consolation of belief, and the undying optimism of a father who taught him the principles of physics on the roller-coaster and the parachute jump.

Partly a portrait of cynical politics and religious fervor, part scientific speculation and even a meditation on the glories of Coney Island, The Lamentations of Julius Marantz traces the rise and fall of science in a truly personal story that finally fairly ascends.