Introduction

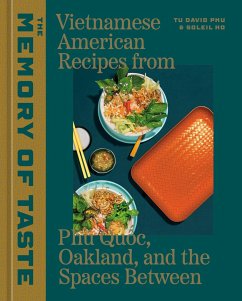

It was always hard to talk to my parents about anything but food. For most of my life, I didn&rsquo t know anything about their past: their childhoods in the Vietnamese island of Phú Quố c or how, as young adults, they escaped from war. Other families might get some warm, chest-deep glow from reminiscing together. That&rsquo s not the case with mine. For my parents, their memories haunt them. They would brush off any questions about the past as quickly as I could ask them. To me, their time in Vietnam was mostly a giant question mark.

While working in fine dining restaurants at the beginning of my career, I was usually the only Viet guy in the kitchen&mdash but it wasn&rsquo t necessarily my racial identity that singled me out. I felt it in those casual moments between rushes in the kitchen, when all the cooks would get to talking about memory and family, in that intimate way that develops when you&rsquo re working elbow-to-elbow and sweating all over each other for twelve hours at a time. Those were the times when we&rsquo d talk about what we ate as kids, our first tastes of perfectly ripe tomatoes, and the way our mothers or grandmothers would massage olive oil into lettuce from their gardens. I say &ldquo we&rdquo here, but I&rsquo m lying. It was them, but it wasn&rsquo t me.

At the time, I saw my family history as this gaping nothingness: a series of silent head shakes, pursed lips, and changed subjects. There was nothing &ldquo respectable&rdquo for me to be nostalgic about&mdash no mind-blowing food moments that would stand up to some bourgie tomato story. Was I going to tell my fellow cooks about all the vegetable scraps and fish heads that my parents would save to keep me and my sister fed, just so they could make jokes about how I grew up eating literal garbage? Hell no! So, when I heard other chefs talk about their upbringings with all the hazy-eyed romance of a Jane Austen novel, I shut up. All I felt was jealousy and resentment.

I don&rsquo t remember when it started, but when I was a kid, I tended to project way too much of what I saw on TV onto my own life. Back in the &rsquo 90s, it was shows like Family Matters, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, and Step by Step that showed me what a &ldquo normal family&rdquo was. When people asked me about my home life, I would stretch the truth a little so we could fit the mold. The way I told it, my dad wasn&rsquo t a fishmonger who worked under-the-table night shifts he was a &ldquo fish expert&rdquo : something vague enough so you could plausibly imagine him taming dolphins at the aquarium. And I would say my mom was a &ldquo seamstress,&rdquo a word that sounded harmless on the surface. What I didn&rsquo t tell them was that she worked in sweatshops, earning a fraction of a penny for each piece of clothing she made. A normal family would work 9-to-5 jobs and eat sloppy joes for dinner. A normal family would be so mentally and physically far away from the nightmare of war that they might as well be on a different planet.

I pieced together the real story of my parents later in life, from sometimesconflicting snippets that I got from relatives in the United States and Vietnam and from hints that my mom would drop as we cooked together. It goes something like this. In Phú Quố c, a conch-shaped island off the southern shores of Cambodia, my parents met at a fish market. My mom, who came from a wealthy family of fish sauce&ndash makers, suddenly noticed the buff young Viet-Khmer guy selling fish that he and his brothers had caught that morning. In the fight between her family&rsquo s disapproval and her feelings, the feelings kicked disapproval&rsquo s ass to the curb. You&rsquo d think that just a tug-of-war between feelings and family would be enough strife and drama for a lifetime. But then there was the war.

It was a war that most Americans still barely know anything about, but it&rsquo s the poison that beats in the heart of my family&rsquo s trauma, so America owes it to my family&mdash and so many others&mdash to at least hear about it. So here goes. From 1965 to 1973, the United States&mdash led by Lyndon B. Johnson and then Richard Nixon&mdash dropped 2.7 million tons of bombs onto Cambodia in what they called &ldquo Operation Menu.&rdquo Out of that chaos rose the Khmer Rouge, a paranoid and genocidal military regime that ruled over Cambodia, waging war on Vietnam as well as on its own people. In the early 1970s, when my parents were still just two teenagers in love, my dad was drafted by the People&rsquo s Army of Vietnam to fight against the Khmer Rouge. I don&rsquo t know what my dad saw back then I only know what came after. When my dad returned, it was to a home scarred by war. He and my mom were certain that if they had stayed, they would have starved. So they left.

Both barely into their twenties, my parents escaped Vietnam by boat. Cut off from home, they were stripped of all their possessions when they were robbed by pirates at sea. They ended up in a Thai refugee camp for nine months. It was at the camp where my mom sewed for money and learned how to utilize and stretch every single scrap of food she was able to get her hands on. Years after they left, that fight for survival and that life-or-death frugality stayed with them, reappearing in our lives every day when we sat down to eat a meal.

It took me so many years to see my family&rsquo s food for what it really was. When you&rsquo re taught in European-style fine dining to only use the most pristine tips of asparagus for a tasting menu course, you develop this ingrained mental hierarchy of what &ldquo good&rdquo and &ldquo bad&rdquo food is. Even if you end up using the not-so-pretty produce for other purposes, you can&rsquo t help but think of it as undesirable or not worth the money. In this environment, it was easy for me to stumble down the slippery slope of thinking that my family&rsquo s food was inferior. From there, it wasn&rsquo t too far of a leap to start feeling ashamed of where I came from. Over the years, I&rsquo ve had to consciously let go of those ideas and drag myself off of my fancy-chef high horse to really appreciate what my parents gave me.

Cooking with my parents led me to a deeper appreciation of our customs and foodways and opened a window to their past. While my mom showed me how to collect strands of corn silk to use in a dish, her fingers working with a master seamstress&rsquo s precision, I caught glimpses of the skills that allowed her to survive in a refugee camp. When my dad would take me grocery shopping, I would hear stories about the long lineage of fishermen he came from while he scrutinized the seafood counter for the best&mdash and most affordable&mdash specimen to bring home. He told me both of my grandfathers were famous free divers on the island, known for diving into the ocean three hundred feet deep to save people from sinking ships.

Those rare times when my parents let their masks slip just a little, I could see into the memories of conflict, alienation, and food insecurity that built them into the people I&rsquo ve known my whole life. The kitchen was the safest place for me to ask, &ldquo I remember this flavor can you tell me more?&rdquo

Everything that I ate growing up was a piece of this huge puzzle that was my family. There were porridges and stir-fries enriched with whatever my dad would bring home after long hours working at Fisherman&rsquo s Wharf in San Francisco. He filled our fridge with scraps: scallop frills, fish bladders, bloodline, and fish heads. My mom would slowly extract all the flavor she could out of the cheapest cuts of meat and fish, simmering fish bones and chicken carcasses on the stove to break down the collagen into nutritious stocks and soups, and I would dart in and out of the kitchen the whole time, tasting each phase of the broth with her. On good days, we&rsquo d have celery, onions, and carrots to add to the stocks. On bad days, we&rsquo d only have rice and instant ramen to eat. The kitchen was stocked with repurposed jars and plastic tubs filled with leftover scraps: orange peels for candying, cucumber seeds, and corn silk, which she&rsquo d sauté to serve on rice.

Anything my mom couldn&rsquo t cook&mdash and that was a high bar to clear&mdash she&rsquo d stir into the soil of her garden. Under her care, inedible animal organs, crushed oyster shells, and spoiled milk transformed American dirt into the passion fruit, brown sugar cane, Thai bird&rsquo s eye chiles, kumquats, and guavas of her home island.

Before I ever got to visit our hometown in Vietnam, I could taste it. My parents brought Phú Quố c home when they laid baskets of fresh herbs, rice paper, and marinated fish on our dinner table and taught me and my sister how to roll everything up into the perfect bite. Fish sauce, the pride of the island, was a constant presence and a reminder of our people&rsquo s resourcefulness and ingenuity. My parents&rsquo memories of home hurt, but even that pain&mdash as raw as it still was decades later&mdash couldn&rsquo t keep them from dropping breadcrumbs for us to follow.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

It was always hard to talk to my parents about anything but food. For most of my life, I didn&rsquo t know anything about their past: their childhoods in the Vietnamese island of Phú Quố c or how, as young adults, they escaped from war. Other families might get some warm, chest-deep glow from reminiscing together. That&rsquo s not the case with mine. For my parents, their memories haunt them. They would brush off any questions about the past as quickly as I could ask them. To me, their time in Vietnam was mostly a giant question mark.

While working in fine dining restaurants at the beginning of my career, I was usually the only Viet guy in the kitchen&mdash but it wasn&rsquo t necessarily my racial identity that singled me out. I felt it in those casual moments between rushes in the kitchen, when all the cooks would get to talking about memory and family, in that intimate way that develops when you&rsquo re working elbow-to-elbow and sweating all over each other for twelve hours at a time. Those were the times when we&rsquo d talk about what we ate as kids, our first tastes of perfectly ripe tomatoes, and the way our mothers or grandmothers would massage olive oil into lettuce from their gardens. I say &ldquo we&rdquo here, but I&rsquo m lying. It was them, but it wasn&rsquo t me.

At the time, I saw my family history as this gaping nothingness: a series of silent head shakes, pursed lips, and changed subjects. There was nothing &ldquo respectable&rdquo for me to be nostalgic about&mdash no mind-blowing food moments that would stand up to some bourgie tomato story. Was I going to tell my fellow cooks about all the vegetable scraps and fish heads that my parents would save to keep me and my sister fed, just so they could make jokes about how I grew up eating literal garbage? Hell no! So, when I heard other chefs talk about their upbringings with all the hazy-eyed romance of a Jane Austen novel, I shut up. All I felt was jealousy and resentment.

I don&rsquo t remember when it started, but when I was a kid, I tended to project way too much of what I saw on TV onto my own life. Back in the &rsquo 90s, it was shows like Family Matters, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, and Step by Step that showed me what a &ldquo normal family&rdquo was. When people asked me about my home life, I would stretch the truth a little so we could fit the mold. The way I told it, my dad wasn&rsquo t a fishmonger who worked under-the-table night shifts he was a &ldquo fish expert&rdquo : something vague enough so you could plausibly imagine him taming dolphins at the aquarium. And I would say my mom was a &ldquo seamstress,&rdquo a word that sounded harmless on the surface. What I didn&rsquo t tell them was that she worked in sweatshops, earning a fraction of a penny for each piece of clothing she made. A normal family would work 9-to-5 jobs and eat sloppy joes for dinner. A normal family would be so mentally and physically far away from the nightmare of war that they might as well be on a different planet.

I pieced together the real story of my parents later in life, from sometimesconflicting snippets that I got from relatives in the United States and Vietnam and from hints that my mom would drop as we cooked together. It goes something like this. In Phú Quố c, a conch-shaped island off the southern shores of Cambodia, my parents met at a fish market. My mom, who came from a wealthy family of fish sauce&ndash makers, suddenly noticed the buff young Viet-Khmer guy selling fish that he and his brothers had caught that morning. In the fight between her family&rsquo s disapproval and her feelings, the feelings kicked disapproval&rsquo s ass to the curb. You&rsquo d think that just a tug-of-war between feelings and family would be enough strife and drama for a lifetime. But then there was the war.

It was a war that most Americans still barely know anything about, but it&rsquo s the poison that beats in the heart of my family&rsquo s trauma, so America owes it to my family&mdash and so many others&mdash to at least hear about it. So here goes. From 1965 to 1973, the United States&mdash led by Lyndon B. Johnson and then Richard Nixon&mdash dropped 2.7 million tons of bombs onto Cambodia in what they called &ldquo Operation Menu.&rdquo Out of that chaos rose the Khmer Rouge, a paranoid and genocidal military regime that ruled over Cambodia, waging war on Vietnam as well as on its own people. In the early 1970s, when my parents were still just two teenagers in love, my dad was drafted by the People&rsquo s Army of Vietnam to fight against the Khmer Rouge. I don&rsquo t know what my dad saw back then I only know what came after. When my dad returned, it was to a home scarred by war. He and my mom were certain that if they had stayed, they would have starved. So they left.

Both barely into their twenties, my parents escaped Vietnam by boat. Cut off from home, they were stripped of all their possessions when they were robbed by pirates at sea. They ended up in a Thai refugee camp for nine months. It was at the camp where my mom sewed for money and learned how to utilize and stretch every single scrap of food she was able to get her hands on. Years after they left, that fight for survival and that life-or-death frugality stayed with them, reappearing in our lives every day when we sat down to eat a meal.

It took me so many years to see my family&rsquo s food for what it really was. When you&rsquo re taught in European-style fine dining to only use the most pristine tips of asparagus for a tasting menu course, you develop this ingrained mental hierarchy of what &ldquo good&rdquo and &ldquo bad&rdquo food is. Even if you end up using the not-so-pretty produce for other purposes, you can&rsquo t help but think of it as undesirable or not worth the money. In this environment, it was easy for me to stumble down the slippery slope of thinking that my family&rsquo s food was inferior. From there, it wasn&rsquo t too far of a leap to start feeling ashamed of where I came from. Over the years, I&rsquo ve had to consciously let go of those ideas and drag myself off of my fancy-chef high horse to really appreciate what my parents gave me.

Cooking with my parents led me to a deeper appreciation of our customs and foodways and opened a window to their past. While my mom showed me how to collect strands of corn silk to use in a dish, her fingers working with a master seamstress&rsquo s precision, I caught glimpses of the skills that allowed her to survive in a refugee camp. When my dad would take me grocery shopping, I would hear stories about the long lineage of fishermen he came from while he scrutinized the seafood counter for the best&mdash and most affordable&mdash specimen to bring home. He told me both of my grandfathers were famous free divers on the island, known for diving into the ocean three hundred feet deep to save people from sinking ships.

Those rare times when my parents let their masks slip just a little, I could see into the memories of conflict, alienation, and food insecurity that built them into the people I&rsquo ve known my whole life. The kitchen was the safest place for me to ask, &ldquo I remember this flavor can you tell me more?&rdquo

Everything that I ate growing up was a piece of this huge puzzle that was my family. There were porridges and stir-fries enriched with whatever my dad would bring home after long hours working at Fisherman&rsquo s Wharf in San Francisco. He filled our fridge with scraps: scallop frills, fish bladders, bloodline, and fish heads. My mom would slowly extract all the flavor she could out of the cheapest cuts of meat and fish, simmering fish bones and chicken carcasses on the stove to break down the collagen into nutritious stocks and soups, and I would dart in and out of the kitchen the whole time, tasting each phase of the broth with her. On good days, we&rsquo d have celery, onions, and carrots to add to the stocks. On bad days, we&rsquo d only have rice and instant ramen to eat. The kitchen was stocked with repurposed jars and plastic tubs filled with leftover scraps: orange peels for candying, cucumber seeds, and corn silk, which she&rsquo d sauté to serve on rice.

Anything my mom couldn&rsquo t cook&mdash and that was a high bar to clear&mdash she&rsquo d stir into the soil of her garden. Under her care, inedible animal organs, crushed oyster shells, and spoiled milk transformed American dirt into the passion fruit, brown sugar cane, Thai bird&rsquo s eye chiles, kumquats, and guavas of her home island.

Before I ever got to visit our hometown in Vietnam, I could taste it. My parents brought Phú Quố c home when they laid baskets of fresh herbs, rice paper, and marinated fish on our dinner table and taught me and my sister how to roll everything up into the perfect bite. Fish sauce, the pride of the island, was a constant presence and a reminder of our people&rsquo s resourcefulness and ingenuity. My parents&rsquo memories of home hurt, but even that pain&mdash as raw as it still was decades later&mdash couldn&rsquo t keep them from dropping breadcrumbs for us to follow.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

![Vietnamese Food Any Day: Simple Recipes for True, Fresh Flavors [A Cookbook] Vietnamese Food Any Day: Simple Recipes for True, Fresh Flavors [A Cookbook]](https://bilder.buecher.de/produkte/52/52642/52642947m.jpg)