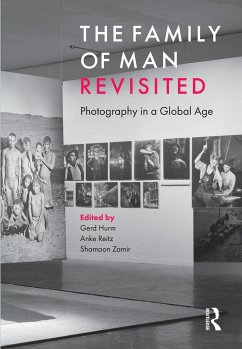

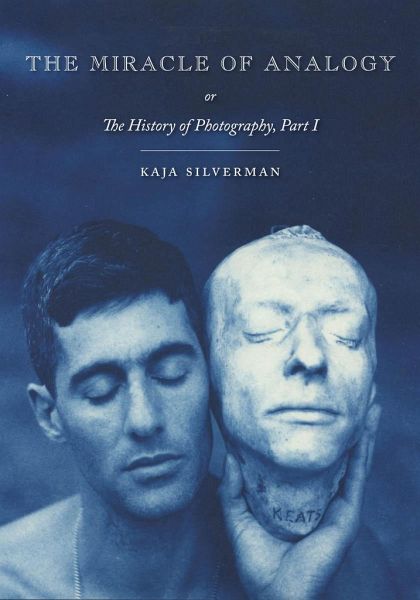

The Miracle of Analogy

Or the History of Photography, Part 1

Versandkostenfrei!

Versandfertig in über 4 Wochen

28,99 €

inkl. MwSt.

PAYBACK Punkte

14 °P sammeln!

This book is the first of a two-volume study of photography that challenges both how photography has been theorized and how it has been historicized.