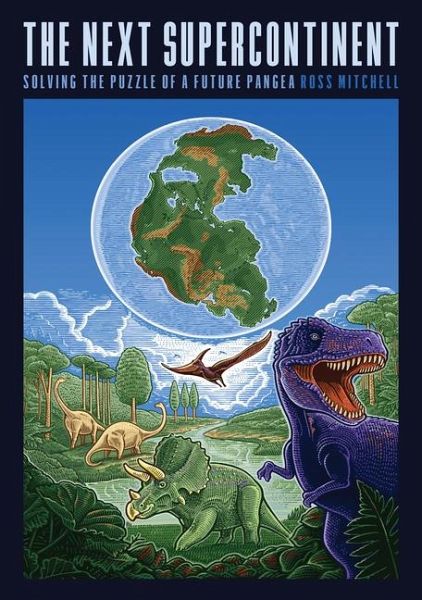

Ross Mitchell is professor at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing. His supercontinent research has been covered by outlets including the New York Times, Scientific American, NPR Science Friday, and Science. In grade school, many of us learned how the present continents, scattered around the globe, once fit snugly together. Although each continent appears to have its own particular shape, rewind the tape 200 million years and they fit together, like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. "Pangea," coined by plate tectonic pioneer Alfred Wegener, means just that: "all Earth," a time in Earth's past when the majority of the continents assembled into a single plate. But Pangea is just the most recent iteration of what's called a supercontinent. At least two others have come and gone over the 4.5 billion years of our planet's existence--and scientists like me believe there will be more in the future. The next supercontinent will likely take another 200 million years to form, but the continents are undeniably on a collision course. According to one computer model, New York City will crash into Lima, Peru. Plate tectonics is certainly powerful enough to stack one city on top of the other, sending the future's equivalent of skyscrapers into the depths of the ocean to be recycled back down into the hot mantle. Although scientists agree that another supercontinent is coming, we have vastly different opinions on how it will take shape. In this book, I will layout the leading contenders for the geography of the next supercontinent, explore the modern mysteries that still surround plate tectonics, and explain the science behind predicting how continents move. Alas, predicting the next supercontinent is not as simple as understanding today's movements and pressing fast-forward. Tectonic plates move slowly, at about the same speed that our fingernails grow. But GPS is now precise enough to detect this slow motion. And residents of Pompeii, San Francisco, and Fukushima can tell you that the effects of those movements are hard to perceive--until they are devastating. Volcanoes, earthquakes, and tsunamis are evidence of plate tectonics' power. So is geography--just look at the abrupt bend, or kink, in the chain of the Hawaiian Islands. These islands formed a straight chain of semicontinuous volcanic activity for about 30 million years, until a sudden pivot occurred over the course of a few million years or less. The bend is a record of that pivot. Why did this happen? The tectonic plates are all interconnected, so any change in the movement of one plate causes adjustments in them all. Thirty million years ago, Australia broke away from Antarctica and started its current path north across the Pacific Ocean. Whereas the Pacific plate had been moving directly north before the bend, Australia's breakaway in the western Pacific caused the motion of the Pacific plate to deflect toward the northwest after the bend. No plate is moving alone and each plate interacts with its neighbors along their shared boundaries. Plate tectonics is the dance of all plates and the seven major continents (or eight, depending on how you define them) they carry, constituting a global choreography, with dozens of smaller plates in between. The earliest understanding of plate movement was the sixteenth-century idea of "continental drift"--that the continents migrated like rafts slowly into their current position, floating on an imperceptible layer within the earth. But this theory was largely written off because it was not clear what sort of mysterious substratum the continental rafts would be floating on. By the beginning of the last century, we still knew very little about the interior of the earth. Eventually, as seismology-- the study of inner Earth using the vibrations generated from earthquakes-- developed and submarines were put to good use after World War II to map the seafloor, the hypothesis of plate tectonics changed geology forever. Breaking Earth's seemingly rigid surface into an interlocking mosaic of different plates that pushed and pulled each other provided a unified explanation for the origin of many of Earth's great geological features, such as mountains, volcanoes, earthquakes, and oceans. But as exciting as the early plate tectonic revolution was, it didn't have all the answers. For example, the hot interior of the earth was likely convecting, in a movement driven by temperature changes, just like the circulation of air in the atmosphere; but how these deep convective cells related to the push and pull of the plates at Earth's surface would remain elusive for decades--and the details of this interaction are still unsolved.