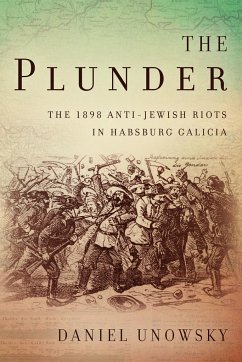

In the spring of 1898, thousands of peasants and townspeople in western Galicia rioted against their Jewish neighbors. Attacks took place in more than 400 communities in this northeastern province of the Habsburg Monarchy, in present-day Poland and Ukraine. Jewish-owned homes and businesses were ransacked and looted, and Jews were assaulted, threatened, and humiliated, though not killed. Emperor Franz Joseph signed off on a state of emergency in thirty-three counties and declared martial law in two. Over five thousand individuals-peasants, day-laborers, city council members, teachers, shopkeepers-were charged with myriad offenses. Seeking to make sense of this violence and its aftermath, The Plunder examines the circulation of antisemitic ideas within Galicia against the political backdrop of the Habsburg state. Daniel Unowsky sees the 1898 anti-Jewish riots as evidence not of Galician backwardness and barbarity, but of a late nineteenth-century Europe reeling from economic, cultural, and political transformations wrought by mass politics, literacy, industrialization, capitalist agriculture, and government expansion. Through its nuanced analysis of the riots as a form of "exclusionary violence," this book offers new insights into the upsurge of the antisemitism that accompanied the emergence of mass politics in Europe at the turn of the twentieth century.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.