Schade – dieser Artikel ist leider ausverkauft. Sobald wir wissen, ob und wann der Artikel wieder verfügbar ist, informieren wir Sie an dieser Stelle.

- Broschiertes Buch

- Merkliste

- Auf die Merkliste

- Bewerten Bewerten

- Teilen

- Produkt teilen

- Produkterinnerung

- Produkterinnerung

Bin Xu is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Emory University.

Andere Kunden interessierten sich auch für

![Operation Brother's Brother Operation Brother's Brother]() Cyril E BryantOperation Brother's Brother28,99 €

Cyril E BryantOperation Brother's Brother28,99 €![The Technology of Policing The Technology of Policing]() Peter K ManningThe Technology of Policing40,99 €

Peter K ManningThe Technology of Policing40,99 €![Narratives of Crisis Narratives of Crisis]() Matthew SeegerNarratives of Crisis34,99 €

Matthew SeegerNarratives of Crisis34,99 €![The Great Displacement The Great Displacement]() Jake BittleThe Great Displacement15,99 €

Jake BittleThe Great Displacement15,99 €![Building Community Resilience to Large Oil Spills Building Community Resilience to Large Oil Spills]() Melissa L FinucaneBuilding Community Resilience to Large Oil Spills23,99 €

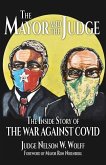

Melissa L FinucaneBuilding Community Resilience to Large Oil Spills23,99 €![The Mayor and The Judge The Mayor and The Judge]() Judge Nelson W WolffThe Mayor and The Judge15,99 €

Judge Nelson W WolffThe Mayor and The Judge15,99 €

Produktdetails

- Produktdetails

- Verlag: Stanford University Press

- Seitenzahl: 256

- Erscheinungstermin: 22. August 2017

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 226mm x 152mm x 18mm

- Gewicht: 340g

- ISBN-13: 9781503603363

- ISBN-10: 1503603369

- Artikelnr.: 47774664

- Herstellerkennzeichnung

- Libri GmbH

- Europaallee 1

- 36244 Bad Hersfeld

- gpsr@libri.de

- Verlag: Stanford University Press

- Seitenzahl: 256

- Erscheinungstermin: 22. August 2017

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 226mm x 152mm x 18mm

- Gewicht: 340g

- ISBN-13: 9781503603363

- ISBN-10: 1503603369

- Artikelnr.: 47774664

- Herstellerkennzeichnung

- Libri GmbH

- Europaallee 1

- 36244 Bad Hersfeld

- gpsr@libri.de

Bin Xu is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Emory University.

Contents and Abstracts

Introduction

chapter abstract

The Introduction presents an overview of the topics, significance, and

theoretical framework of the book.

1Consensus Crisis

chapter abstract

This chapter explores the massive wave of volunteer work in the aftermath

of the Sichuan earthquake and examines how the volunteers themselves

understood the meaning of their volunteering. The earthquake forced both

the state and civic associations to solve pressing issues related to the

emergency response instead of confronting each other. This created a

"consensus crisis" where, in the face of crisis, different parties reached

a consensus on goals and priorities. This in turn enabled civic

associations to exercise the capacity they had built up in preceding

decades. While all the participants expressed their compassion for the

victims and their solidarity with fellow volunteers, the meaning they

attached to their actions were multivocal and diverse. Most of the

meanings, however, did not reflect classical Western notions of civil

society, such as liberty and equality, but instead drew on nationalistic

sentiment, religion, and a discourse of individualism.

2Mourning for the Ordinary

chapter abstract

This chapter examines how public intellectuals and liberal media proposed a

national mourning observance and why the proposal became a reality in the

wake of the Sichuan earthquake, whereas there had been no national mourning

for victims of previous disasters. The mourning for the victims of the

Sichuan earthquake was historically unprecedented because, unlike past

instances of national mourning, which had been restricted to the deaths of

state leaders and soldiers, it was a mourning for ordinary citizens. This

was a result of the development of the Chinese public sphere in recent

decades, in both its institutional capacity and its moral ideas about

ordinary people's value. This development was catalyzed by the Chinese

state's concern with its image after a series of political crises in the

year of the Olympics.

3Civic Engagement in the Recovery Period

chapter abstract

This chapter analyzes the civic engagement in the recovery period. During

this time, the consensus crisis dissolved when the state-business alliance

came to dominate the recovery plans and the state, out of political

considerations, restricted civic associations' activities. The

post-earthquake civic engagement did not lead to significant long-term

changes in the structural relations between the state and civil society.

Changes in the political context, however, shaped how the volunteers

understood and talked about their engagement, particularly when they faced

an ethical-political dilemma about the school collapse issue. Most of them

became apathetic and avoided the school collapse issue because of their

inability to change the social and political factors that had led to shoddy

construction, the normalization of the disaster as an acceptable pathology,

and a reluctance to talk about it due to national pride.

4Forgetting, Remembering, and Activism

chapter abstract

This chapter examines how a "tiny public" of dissidents and intellectuals

countered the state's forced remembering and forgetting by collecting the

student victims' names and producing commemorative objects. Participants in

the commemorative activism clearly articulated the meanings of their

actions, which were similar to the classical normative ideas of civil

society, such as individual liberty and the value of ordinary people's

lives. Their engagement can be explained by their life experience and their

prior involvement in the tiny public's activities. They significantly

changed the memory of the earthquake in the world outside China, but their

influence on memory within China was limited.

Conclusion

chapter abstract

The Conclusion presents a comparative case, the 2010 Yushu earthquake, to

recapitulate the major arguments of the book and discusses the book's

contributions to understanding civic engagement and civil society in China.

Introduction

chapter abstract

The Introduction presents an overview of the topics, significance, and

theoretical framework of the book.

1Consensus Crisis

chapter abstract

This chapter explores the massive wave of volunteer work in the aftermath

of the Sichuan earthquake and examines how the volunteers themselves

understood the meaning of their volunteering. The earthquake forced both

the state and civic associations to solve pressing issues related to the

emergency response instead of confronting each other. This created a

"consensus crisis" where, in the face of crisis, different parties reached

a consensus on goals and priorities. This in turn enabled civic

associations to exercise the capacity they had built up in preceding

decades. While all the participants expressed their compassion for the

victims and their solidarity with fellow volunteers, the meaning they

attached to their actions were multivocal and diverse. Most of the

meanings, however, did not reflect classical Western notions of civil

society, such as liberty and equality, but instead drew on nationalistic

sentiment, religion, and a discourse of individualism.

2Mourning for the Ordinary

chapter abstract

This chapter examines how public intellectuals and liberal media proposed a

national mourning observance and why the proposal became a reality in the

wake of the Sichuan earthquake, whereas there had been no national mourning

for victims of previous disasters. The mourning for the victims of the

Sichuan earthquake was historically unprecedented because, unlike past

instances of national mourning, which had been restricted to the deaths of

state leaders and soldiers, it was a mourning for ordinary citizens. This

was a result of the development of the Chinese public sphere in recent

decades, in both its institutional capacity and its moral ideas about

ordinary people's value. This development was catalyzed by the Chinese

state's concern with its image after a series of political crises in the

year of the Olympics.

3Civic Engagement in the Recovery Period

chapter abstract

This chapter analyzes the civic engagement in the recovery period. During

this time, the consensus crisis dissolved when the state-business alliance

came to dominate the recovery plans and the state, out of political

considerations, restricted civic associations' activities. The

post-earthquake civic engagement did not lead to significant long-term

changes in the structural relations between the state and civil society.

Changes in the political context, however, shaped how the volunteers

understood and talked about their engagement, particularly when they faced

an ethical-political dilemma about the school collapse issue. Most of them

became apathetic and avoided the school collapse issue because of their

inability to change the social and political factors that had led to shoddy

construction, the normalization of the disaster as an acceptable pathology,

and a reluctance to talk about it due to national pride.

4Forgetting, Remembering, and Activism

chapter abstract

This chapter examines how a "tiny public" of dissidents and intellectuals

countered the state's forced remembering and forgetting by collecting the

student victims' names and producing commemorative objects. Participants in

the commemorative activism clearly articulated the meanings of their

actions, which were similar to the classical normative ideas of civil

society, such as individual liberty and the value of ordinary people's

lives. Their engagement can be explained by their life experience and their

prior involvement in the tiny public's activities. They significantly

changed the memory of the earthquake in the world outside China, but their

influence on memory within China was limited.

Conclusion

chapter abstract

The Conclusion presents a comparative case, the 2010 Yushu earthquake, to

recapitulate the major arguments of the book and discusses the book's

contributions to understanding civic engagement and civil society in China.

Contents and Abstracts

Introduction

chapter abstract

The Introduction presents an overview of the topics, significance, and

theoretical framework of the book.

1Consensus Crisis

chapter abstract

This chapter explores the massive wave of volunteer work in the aftermath

of the Sichuan earthquake and examines how the volunteers themselves

understood the meaning of their volunteering. The earthquake forced both

the state and civic associations to solve pressing issues related to the

emergency response instead of confronting each other. This created a

"consensus crisis" where, in the face of crisis, different parties reached

a consensus on goals and priorities. This in turn enabled civic

associations to exercise the capacity they had built up in preceding

decades. While all the participants expressed their compassion for the

victims and their solidarity with fellow volunteers, the meaning they

attached to their actions were multivocal and diverse. Most of the

meanings, however, did not reflect classical Western notions of civil

society, such as liberty and equality, but instead drew on nationalistic

sentiment, religion, and a discourse of individualism.

2Mourning for the Ordinary

chapter abstract

This chapter examines how public intellectuals and liberal media proposed a

national mourning observance and why the proposal became a reality in the

wake of the Sichuan earthquake, whereas there had been no national mourning

for victims of previous disasters. The mourning for the victims of the

Sichuan earthquake was historically unprecedented because, unlike past

instances of national mourning, which had been restricted to the deaths of

state leaders and soldiers, it was a mourning for ordinary citizens. This

was a result of the development of the Chinese public sphere in recent

decades, in both its institutional capacity and its moral ideas about

ordinary people's value. This development was catalyzed by the Chinese

state's concern with its image after a series of political crises in the

year of the Olympics.

3Civic Engagement in the Recovery Period

chapter abstract

This chapter analyzes the civic engagement in the recovery period. During

this time, the consensus crisis dissolved when the state-business alliance

came to dominate the recovery plans and the state, out of political

considerations, restricted civic associations' activities. The

post-earthquake civic engagement did not lead to significant long-term

changes in the structural relations between the state and civil society.

Changes in the political context, however, shaped how the volunteers

understood and talked about their engagement, particularly when they faced

an ethical-political dilemma about the school collapse issue. Most of them

became apathetic and avoided the school collapse issue because of their

inability to change the social and political factors that had led to shoddy

construction, the normalization of the disaster as an acceptable pathology,

and a reluctance to talk about it due to national pride.

4Forgetting, Remembering, and Activism

chapter abstract

This chapter examines how a "tiny public" of dissidents and intellectuals

countered the state's forced remembering and forgetting by collecting the

student victims' names and producing commemorative objects. Participants in

the commemorative activism clearly articulated the meanings of their

actions, which were similar to the classical normative ideas of civil

society, such as individual liberty and the value of ordinary people's

lives. Their engagement can be explained by their life experience and their

prior involvement in the tiny public's activities. They significantly

changed the memory of the earthquake in the world outside China, but their

influence on memory within China was limited.

Conclusion

chapter abstract

The Conclusion presents a comparative case, the 2010 Yushu earthquake, to

recapitulate the major arguments of the book and discusses the book's

contributions to understanding civic engagement and civil society in China.

Introduction

chapter abstract

The Introduction presents an overview of the topics, significance, and

theoretical framework of the book.

1Consensus Crisis

chapter abstract

This chapter explores the massive wave of volunteer work in the aftermath

of the Sichuan earthquake and examines how the volunteers themselves

understood the meaning of their volunteering. The earthquake forced both

the state and civic associations to solve pressing issues related to the

emergency response instead of confronting each other. This created a

"consensus crisis" where, in the face of crisis, different parties reached

a consensus on goals and priorities. This in turn enabled civic

associations to exercise the capacity they had built up in preceding

decades. While all the participants expressed their compassion for the

victims and their solidarity with fellow volunteers, the meaning they

attached to their actions were multivocal and diverse. Most of the

meanings, however, did not reflect classical Western notions of civil

society, such as liberty and equality, but instead drew on nationalistic

sentiment, religion, and a discourse of individualism.

2Mourning for the Ordinary

chapter abstract

This chapter examines how public intellectuals and liberal media proposed a

national mourning observance and why the proposal became a reality in the

wake of the Sichuan earthquake, whereas there had been no national mourning

for victims of previous disasters. The mourning for the victims of the

Sichuan earthquake was historically unprecedented because, unlike past

instances of national mourning, which had been restricted to the deaths of

state leaders and soldiers, it was a mourning for ordinary citizens. This

was a result of the development of the Chinese public sphere in recent

decades, in both its institutional capacity and its moral ideas about

ordinary people's value. This development was catalyzed by the Chinese

state's concern with its image after a series of political crises in the

year of the Olympics.

3Civic Engagement in the Recovery Period

chapter abstract

This chapter analyzes the civic engagement in the recovery period. During

this time, the consensus crisis dissolved when the state-business alliance

came to dominate the recovery plans and the state, out of political

considerations, restricted civic associations' activities. The

post-earthquake civic engagement did not lead to significant long-term

changes in the structural relations between the state and civil society.

Changes in the political context, however, shaped how the volunteers

understood and talked about their engagement, particularly when they faced

an ethical-political dilemma about the school collapse issue. Most of them

became apathetic and avoided the school collapse issue because of their

inability to change the social and political factors that had led to shoddy

construction, the normalization of the disaster as an acceptable pathology,

and a reluctance to talk about it due to national pride.

4Forgetting, Remembering, and Activism

chapter abstract

This chapter examines how a "tiny public" of dissidents and intellectuals

countered the state's forced remembering and forgetting by collecting the

student victims' names and producing commemorative objects. Participants in

the commemorative activism clearly articulated the meanings of their

actions, which were similar to the classical normative ideas of civil

society, such as individual liberty and the value of ordinary people's

lives. Their engagement can be explained by their life experience and their

prior involvement in the tiny public's activities. They significantly

changed the memory of the earthquake in the world outside China, but their

influence on memory within China was limited.

Conclusion

chapter abstract

The Conclusion presents a comparative case, the 2010 Yushu earthquake, to

recapitulate the major arguments of the book and discusses the book's

contributions to understanding civic engagement and civil society in China.