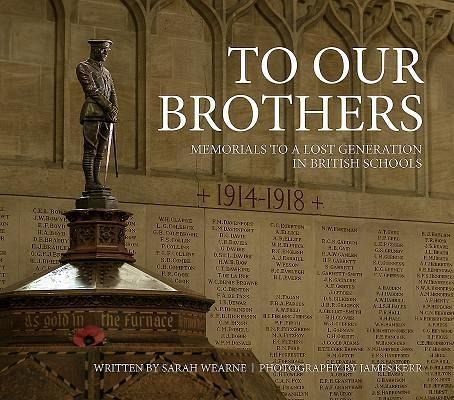

To Our Brothers

Memorials to a Lost Generation in British Schools

Illustrator: Kerr, James

Versandkostenfrei!

Versandfertig in über 4 Wochen

43,99 €

inkl. MwSt.

PAYBACK Punkte

22 °P sammeln!

To Our Brothers: Memorials to a Lost Generation British Schools shows how a nation not noted for its ability to express emotion, in fact famous for its stiff upper lip, managed to convey its grief, love and pride for some of the thousands of its young men who were killed during the First World War. Schools had a peculiarly intense relationship with their dead, especially boarding schools. Most of them were much smaller than they are today, pupils spent more time there, there were fewer exeats and some boys, whose parents lived abroad, even remained at school during the holidays. All of which g...

To Our Brothers: Memorials to a Lost Generation British Schools shows how a nation not noted for its ability to express emotion, in fact famous for its stiff upper lip, managed to convey its grief, love and pride for some of the thousands of its young men who were killed during the First World War. Schools had a peculiarly intense relationship with their dead, especially boarding schools. Most of them were much smaller than they are today, pupils spent more time there, there were fewer exeats and some boys, whose parents lived abroad, even remained at school during the holidays. All of which gave real meaning to the term alma mater, nurturing mother, and in loco parentis, in place of a parent. Many boys went straight from school into the services and were dead within a year. The staff still knew them and grieved for them as they might for their own sons, and in some cases the dead were their own sons. The book will show how schools used the language of Britain¿s past, its cultural heritage ¿ history, religion, customs, art, architecture, literature and myth ¿ to articulate their emotions, to make their memorials speak. But it¿s a language the twenty-first century doesn¿t speak very well anymore. It doesn¿t pick up the biblical and literary allusions, understand the architectural forms, or recognise the symbolic references. By looking at the memorials in fifty schools across Britain, small grammar schools to the great public schools, chapels to sports pavilions, jewelled altar crosses to sundials, objects made of stone, wood, stained glass, brass, silver, bronze, gold leaf, parchment and paper, all nuanced by their cultural references, the author shows how school memorials were able to express a complex raft of emotions. The book has been beautifully and atmospherically illustrated with numerous colour photographs that do great justice to the memorials that are in some cases the work of masters of the Arts and Crafts movement and the best-known architects of the day, and to others that are simply the affecting work of a parent or the school¿s art master. There are many previously unknown treasures among the collection, some of them previously unknown to the schools themselves.