A.B. Yehoshua

Gebundenes Buch

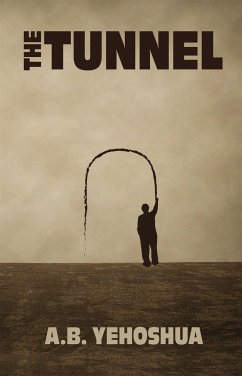

Tunnel

Versandkostenfrei!

Versandfertig in 2-4 Wochen

PAYBACK Punkte

8 °P sammeln!

Tunnel

Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Produktdetails

- Verlag: HarperCollins

- Seitenzahl: 336

- Abmessung: 154mm x 216mm x 34mm

- Gewicht: 460g

- ISBN-13: 9781328622631

- Artikelnr.: 56710710

Herstellerkennzeichnung

Die Herstellerinformationen sind derzeit nicht verfügbar.

Slowly he is deteriorating and the verdict is clear: dementia. Zvi Luria, former road engineer, struggles with the diagnosis and the effects of the illness: increasingly, he is forgetting first names and once he could only be stopped at the last moment from picking up another boy than his grandchild …

Mehr

Slowly he is deteriorating and the verdict is clear: dementia. Zvi Luria, former road engineer, struggles with the diagnosis and the effects of the illness: increasingly, he is forgetting first names and once he could only be stopped at the last moment from picking up another boy than his grandchild from kindergarten. When he is invited to a farewell party of a former colleague, he visits his old office where he stumbles upon Asael Maimoni, the son of his last legal adviser, who is now occupying his post. Luria’s wife thinks it would be a good idea to get her husband’s brain filled with work again and thus he becomes Maimoni’s unpaid assistant in planning a tunnel in the Negev desert. When working on the road, he not only profits from his many years of experience that he can successfully use despite his slowly weakening memory, but he also learns a lot about his own country and the people he never tried to really get to know.

Yehoshua is one of the best known contemporary Israeli writers and professor of Hebrew Literature. He has been awarded numerous prizes for his work and his novels have been translated into many languages. Over and over again, Israel’s politics and the Jewish identity have been central in his works and this also plays an important part in his latest novel.

“The tunnel” addresses several discussion worthy topics. First of all, quite obviously, Luria’s dementia, what it does to him and how the old man and his surroundings cope with it. In an ageing society, this is something we all have come across and it surely isn’t an easy illness to get by since, on the one hand, physically, the people affected are totally healthy, but, on the other hand, the loss of memory gradually makes them lose independence and living with them becomes more challenging. If, like Luria, they are aware of the problems, this can especially hard if they had an intellectually demanding professional life and now experience themselves degraded to a child.

The second noteworthy aspect is the road-building which is quickly connected to the core Israeli question of how they treat non-Jewish residents and their culture. Not only an Arab family in hiding, due to a failed attempt to help them by a former commanding officer of the forces, opens Luria’s eyes on what is going on at the border clandestinely but with good intentions, but he also witnesses how officials treat the nomad tribe of Nabateans and their holy sites.

On a more personal level, the novel also touches questions of guilt and bad conscience as well as the possibility of changing your mind and behaviour even at an older age.

Wonderfully narrated with an interesting and loveable protagonist, it was a great joy to read this novel that I can highly recommend.

Weniger

Antworten 0 von 0 finden diese Rezension hilfreich

Antworten 0 von 0 finden diese Rezension hilfreich

Andere Kunden interessierten sich für