Nicht lieferbar

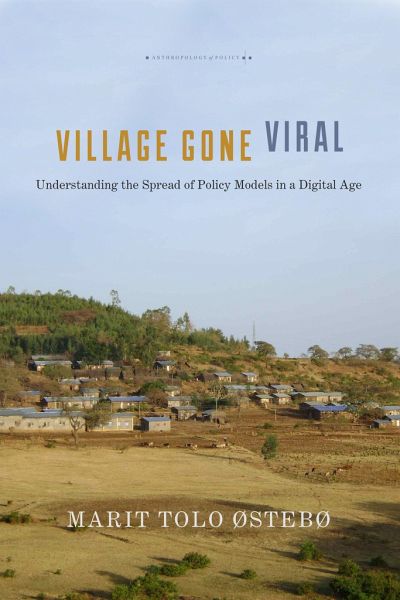

Village Gone Viral

Understanding the Spread of Policy Models in a Digital Age

Versandkostenfrei!

Nicht lieferbar

"In 2001, Ethiopian Television aired a documentary about a small, rural village called Awra Amba. It told the story of a self-sustaining and gender-equal community, where women ploughed, men worked in the kitchen, and so-called 'Harmful Traditional Practices' did not exist. The narrative radically challenged prevailing images of Ethiopia as a gender-conservative and aid-dependent place. Soon, Awra Amba became a model for gender equality and sustainable development in Ethiopia and well beyond. Based on ethnographic research in Ethiopia, Europe, the United States, and via the Internet, Marit [st...

"In 2001, Ethiopian Television aired a documentary about a small, rural village called Awra Amba. It told the story of a self-sustaining and gender-equal community, where women ploughed, men worked in the kitchen, and so-called 'Harmful Traditional Practices' did not exist. The narrative radically challenged prevailing images of Ethiopia as a gender-conservative and aid-dependent place. Soon, Awra Amba became a model for gender equality and sustainable development in Ethiopia and well beyond. Based on ethnographic research in Ethiopia, Europe, the United States, and via the Internet, Marit [steb² uses the Awra Amba case as a point of departure to examine the widespread circulation and use of models and modeling practices in an increasingly transnational policy world. With a particular focus on traveling models--policy models that become 'viral', that spread widely across different localities through various vectors, ranging from NGOs and multilateral organization to the Internet--this manuscript critically examines how the model paradigm plays out in contexts governed and informed by the politics of metrics and result-driven sustainable development goals. [steb² shows that while a model as a policy or policy tool may appear emancipatory from a global or national perspective, the consequences of being a model may be more ambivalent locally, increasing social inequalities, reinforcing social stratification, and concealing injustice. Village Gone Viral ultimately calls for a reflexive critical anthropology of the production, circulation and use of models as instruments for social change, that explores the power-knowledge effects of models, particularly those that offer themselves as liberatory, at multiple scales and in relation to various actors and media"--