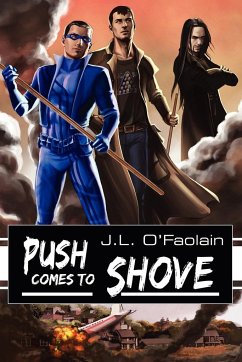

Clint Trafton

Broschiertes Buch

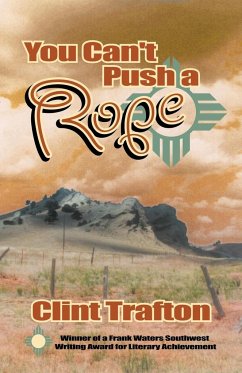

You Can't Push a Rope

Versandkostenfrei!

Versandfertig in 1-2 Wochen

PAYBACK Punkte

12 °P sammeln!

This book is about New Mexicans caught up in the land grant struggle that began following the Mexican-American war and which continues to blister to the surface even today. You Can't Push A Rope focuses on the especially turbulent 1960s when activist Reies Tijerina became the internationally known leader of the Hispanic civil rights movement in America.

Education: Public schools of Albuquerque NM. Bachelor of Science in Electrical Engineering and Master of Science in Experimental Psychology at the University of New Mexico. PhD in Experimental Psychology at the University of Illinois. Experience: Printer at the Albuquerque Journal, Associate Engineer at Boeing Airplane Co., Assistant Professor at Pomona College, Associate Professor at the University of Arizona, maker of fine furniture, straw bale home builder. Accomplishments: Designed and produced a line of fine custom furniture made of mesquite, copper and leather. Published scholarly articles in psychology journals and woodworking magazines. Self-published a small book of short stories. Won a literary award in the 1997 Southwestern Writers Contest with You Can't Push A Rope, the present novel and is working on a second while building his straw bale house in the Jemez mountains of New Mexico. Contact Clint at 505-829-9195 or email ctjemez@yahoo.com Chapter 1 JUNE 1942. "Sit here, on my right," Santiago said to Joaquin at the first breakfast."I need a strong right hand to replace your father's absence and cowardice." Joaquin was angered by the harsh words but something in the old man's eyes convinced him not to show it. Nearly six feet tall and lean for his years with pencil-trimmed mustache and weather-worn face, Santiago looked like someone accustomed to being obeyed without question by men much older than his oldest grandson. Grandmother Lupe brushed a strand of gray hair from her face as she struggled to fit her hefty frame to the kitchen chair and said, "You and your son may not be talking to each other but that is no reason to speak badly of Jose in front of your grandson. He sent the boy to us for the summer, didn't he?" Joaquin glanced at Santiago and, with eyes averted, said, "Well really, it was mom's idea that I come. She said I had to know my family even if grandpa Santiago is a little loco." "Ha! You see, mujer? I knew my son would not want my grandson to know the facts." Santiago shoveled in his food as he spoke, punctuating his words with a rolled tortilla. After the meal, Santiago stood and walked toward the door ordering over his shoulder, "Come.There are things I want you to see." Joaquin jumped to follow and as he trotted after Santiago toward the pickup, Grandmother Lupe watched through the screen door and marveled at how much the boy resembled his grandfather when she first met him. Same wiry thin but strong build, same curly black hair and eyes, same high cheek bones and handsome face. God willing, she prayed quietly to herself, he will not face the same hardships. She finished her prayer with the sign of the cross and touched the silver Virgin of Guadalupe which she wore always around her neck. Santiago and Joaquin drove out of the sleeping village past barbed wire and weathered gray wooden fences and adobe walls.The sun, filtered first through the forest to the east, began to reflect off sheet metal roofs. Clouds were already forming for the afternoon thundershower and carried pink edges in the sunrise. The dirt road rose quickly, becoming rougher as they climbed, more or less following a small creek through grassy meadows alternating with groves of white-trunked aspen or dark tangles of spruce and ponderosa, too thick to walk through. Twice, Joaquin saw deer bound away from the road deeper into the woods as they passed. Santiago said nothing as he repeatedly shifted gears up and down and the pickup whined and rattled its complaint.They crossed the creek, running much wider and deeper here at 10,000 feet than the trickle back in the village of Canjilon, and came out on what seemed to Joaquin like the top of the world. The steep rise of mountains ended, changing to a vast expanse of undulating hills, covered with grass, devoid

Produktdetails

- Verlag: Trafford Publishing

- Seitenzahl: 316

- Erscheinungstermin: 30. Mai 2000

- Englisch

- Abmessung: 216mm x 140mm x 19mm

- Gewicht: 448g

- ISBN-13: 9781552123386

- ISBN-10: 1552123383

- Artikelnr.: 21288541

Herstellerkennzeichnung

Libri GmbH

Europaallee 1

36244 Bad Hersfeld

gpsr@libri.de

Für dieses Produkt wurde noch keine Bewertung abgegeben. Wir würden uns sehr freuen, wenn du die erste Bewertung schreibst!

Eine Bewertung schreiben

Eine Bewertung schreiben

Andere Kunden interessierten sich für