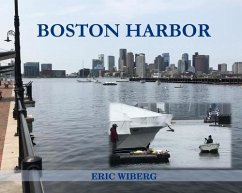

This book aims to be unusual; there is very little text, as the images are meant to be self-explanatory. Themes such as weather, geography, wind, snow, rain, fog and dark all become characters of sorts, as do the vessels themselves. Often the vessels being photographed are difficult to distinguish against the buildings and maritime clutter. That is intentional; these different industrial craft are part of the fabric, yet also to many are invisible. Though the reader cannot hear the VHF radios cackle, and the slap of a ship's wake hitting one's boat, or the wind lifting and dropping awnings like the sigh of bellows, and the churn of a faithful propeller around the debris which is a constant threat to all except the biggest ships, the hope is that the images will provide some kind of tactile experience and exposure.

Boston Harbor is an extraordinary and busy and lively and commercial place. It is also a danger-fraught region of the nations' waterways where global mega-ships carrying cargoes that range from cars to Egyptian salt to gypsum intermingle with cross-harbor water-taxis and water workers of all stripes and dialects in all conditions, dark, foggy, and bright. The several radio frequencies convey a myriad of accents from far eastern to colloquial Boston and Charlestown; Braintree and the Bayou and maritime academies all mixed, whether raising a bridge or requesting permission to pass, or inquiring whether a certain boat may have cables out, that might trip up your boat.

The central characters of this book are not buildings, but boats; not people so much as the weather they are constantly adjusting to. There is a cycle at play; on a summer afternoon it seems like a delicate ballet as unspoken rules allow a dozen boats to untangle from a wharf without hitting each other. That cycle can turn brutal as smaller vessels struggle against three-or-four-foot waves, four runs of powerful current daily, each at least nine feet high, debris, radio messages not received, very cold conditions, challenging lack of visibility, and pure tedium.

No camera tripod was used in the making of this book. Nor was a "camera" in the traditional sense, and nor was a professional photographer utilized. The craft photographed include survey boats to whale watchers, tugs, push-boats, oil-supply boats (called bunker barges), others carrying distillates like methanol, some anchored, some public safety boats whizzing by well lit, others rowing, or in fast dinghies, paddle boards, electric-powered boards, and little Sunfish. These, meanwhile were all being dodged by ferries to Hingham, Hull, Provincetown, Salem, the casino in Everett, commuter boats to Lovejoy and Constitution Wharf; massive cruise ships, LNG tankers, product tankers and articulated tug and barges; all in a day's work, and more.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.

Boston Harbor is an extraordinary and busy and lively and commercial place. It is also a danger-fraught region of the nations' waterways where global mega-ships carrying cargoes that range from cars to Egyptian salt to gypsum intermingle with cross-harbor water-taxis and water workers of all stripes and dialects in all conditions, dark, foggy, and bright. The several radio frequencies convey a myriad of accents from far eastern to colloquial Boston and Charlestown; Braintree and the Bayou and maritime academies all mixed, whether raising a bridge or requesting permission to pass, or inquiring whether a certain boat may have cables out, that might trip up your boat.

The central characters of this book are not buildings, but boats; not people so much as the weather they are constantly adjusting to. There is a cycle at play; on a summer afternoon it seems like a delicate ballet as unspoken rules allow a dozen boats to untangle from a wharf without hitting each other. That cycle can turn brutal as smaller vessels struggle against three-or-four-foot waves, four runs of powerful current daily, each at least nine feet high, debris, radio messages not received, very cold conditions, challenging lack of visibility, and pure tedium.

No camera tripod was used in the making of this book. Nor was a "camera" in the traditional sense, and nor was a professional photographer utilized. The craft photographed include survey boats to whale watchers, tugs, push-boats, oil-supply boats (called bunker barges), others carrying distillates like methanol, some anchored, some public safety boats whizzing by well lit, others rowing, or in fast dinghies, paddle boards, electric-powered boards, and little Sunfish. These, meanwhile were all being dodged by ferries to Hingham, Hull, Provincetown, Salem, the casino in Everett, commuter boats to Lovejoy and Constitution Wharf; massive cruise ships, LNG tankers, product tankers and articulated tug and barges; all in a day's work, and more.

Dieser Download kann aus rechtlichen Gründen nur mit Rechnungsadresse in A, D ausgeliefert werden.

Hinweis: Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.