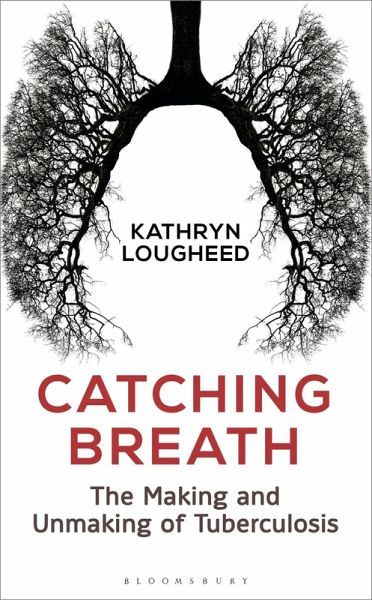

Catching Breath (eBook, ePUB)

The Making and Unmaking of Tuberculosis

PAYBACK Punkte

5 °P sammeln!

Tuberculosis is an ancient disease, but it's not a disease of history. With more than a million victims every year - more than any other disease, including malaria - and antibiotic resistance now found in every country worldwide, tuberculosis is once again proving itself to be one of the smartest killers humanity has ever faced. But it's hardly surprising considering how long it's had to hone its skills. Forty-thousand years ago, our ancestors set off from the cradle of civilisation on their journey towards populating the planet. Tuberculosis hitched a lift and came with us, and it's been ther...

Tuberculosis is an ancient disease, but it's not a disease of history. With more than a million victims every year - more than any other disease, including malaria - and antibiotic resistance now found in every country worldwide, tuberculosis is once again proving itself to be one of the smartest killers humanity has ever faced. But it's hardly surprising considering how long it's had to hone its skills. Forty-thousand years ago, our ancestors set off from the cradle of civilisation on their journey towards populating the planet. Tuberculosis hitched a lift and came with us, and it's been there ever since; waiting, watching, and learning. In The Robber of Youth, Kathryn Lougheed, a former TB research scientist, tells the story of how tuberculosis and humanity have grown up together, with each being shaped by the other in more ways than you could imagine. This relationship between man and microbe has spanned many millennia and has left its mark on both species. We can see evidence of its constant shadow in our genes; in the bones of the ancient dead; in art, music and literature. Tuberculosis has shaped societies - and it continues to do so today. The organism responsible for TB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, has had plenty of time to adapt to its chosen habitat - human lungs - and has learnt through natural selection to be an almost perfect pathogen. Using our own immune cells as a Trojan Horse to aid its spread, it's come up with clever ways to avoid being killed by antibiotics. But patience has been its biggest lesson - the bacterium can enter into a latent state when times are tough, only to come back to life when a host's immune system can no longer put up a fight. Today, more than one million people die of the disease every year and around one-third of the world's population are believed to be infected. That's more than two billion people. Throw in the compounding problems of drug resistance, the HIV epidemic and poverty, and it's clear that tuberculosis remains one of the most serious problems in world medicine. The Robber of Youth follows the history of TB through the ages, from its time as an infection of hunter-gatherers to the first human villages, which set it up with everything it needed to become the monstrous disease it is today, through to the perils of industrialisation and urbanisation. It goes on to look at the latest research in fighting the disease, with stories of modern scientific research, interviews doctors on the frontline treating the disease, and the personal experiences of those affected by TB.