Many long days and nights ago his name was spoken by a person he remembers loving, remembers loving him, remembers leaving him. To fetch food, she said, stay here. Please, Chandra, stay here. That was the last thing he ever heard her say. Please, and then his name, and then, stay here. He stayed there and she never came back. But she left him his name. Chandra.

So this he knows: Chandra. That is his name. That is one of the things he knows.

Other things he knows: He knows what you can eat, and what you cannot eat. He knows what tastes good, what does not taste good. He knows what will make you sick if you eat it or drink it and what will not.

And he knows: The pain that comes from lack of food. The pain that now has made his stomach a home. The pain he knows is called hunger. He knows that word.

And he knows: His alley, the one that houses his shelter. And he knows dust, he knows heat, he knows the suspicious eyes of strangers, he knows the satisfaction of water.

And he knows: The sun rising is morning, is fresh hunger. He knows the sun sinking and sinking into dark is night, is sleep, is un-knowing, is freedom, where you can dream of food, no longer haunted by its painful shadow, though it never truly leaves prodding him from above or belowhe never settles on whichjust as a reminder that it is still there, not going anywhere.

The sun, the monster sun, orange and gigantic beyond the rim of roof-tops and hot already, bakes the dream of food away and prompts him awake with unfriendly beams. He was eating: Fish, fried fish, crisp and dripping with spicy oil, a mountain of rice in his hand and fried fish, always eating in his dream, and most of the time fried fish with rice, good to put in your mouth, to chew, to swallow, fried fish and a mountain or rice.

His eyes open upon the many brown strands above him crisscrossing into the jute sack that is ceiling and roof both. To keep the big sky out, to keep his sky in. To keep the sun out, or much of it, but it's no good against rain. When the rains come he must find more cardboard, or even better some corrugated plastic or metal to keep it out. But the rains are far off, not of concern right now.

He sits up, feels his hair matted against his skull, stiff from dust and dried sweat. He runs small, bony, dirty fingers through it, pulls it out and back over his shoulders, then rubs his eyes.

He is hungry, he knows that word. He is also thirsty, another word he knows well. Opening his eyes again, his nose comes awake too, and with it the many smells stirring around him under the new sun. The smells are of urine and feces, of disease and of many sweaty and dirty bodies in their many sheds up and down the alley but he knows no names for these smells, is not bothered by them, is used to them, alley smells, morning smells. ...

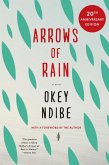

Dieser Download kann aus rechtlichen Gründen nur mit Rechnungsadresse in A, B, CY, CZ, D, DK, EW, E, FIN, F, GR, H, IRL, I, LT, L, LR, M, NL, PL, P, R, S, SLO, SK ausgeliefert werden.