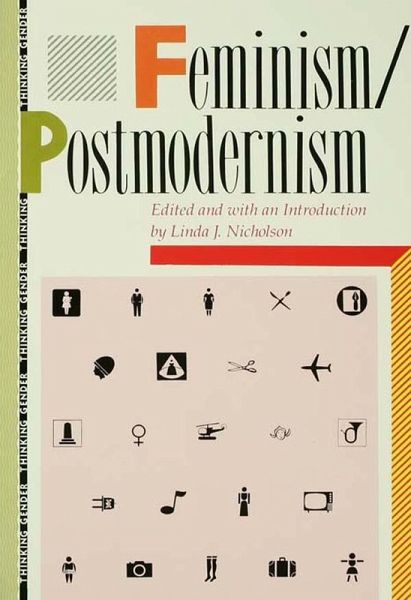

Feminism/Postmodernism (eBook, PDF)

Versandkostenfrei!

Sofort per Download lieferbar

36,95 €

inkl. MwSt.

Weitere Ausgaben:

PAYBACK Punkte

18 °P sammeln!

In this anthology, prominent contemporary theorists assess the benefits and dangers of postmodernism for feminist theory. The contributors examine the meaning of postmodernism both as a methodological position and a diagnosis of the times. They consider such issues as the nature of personal and social identity today, the political implications of recent aesthetic trends, and the consequences of changing work and family relations on women's lives. Contributors: Seyla Benhabib, Susan Bordo, Judith Butler, Christine Di Stefano, Jane Flax, Nancy Fraser, Donna Haraway, Sandra Harding, Nancy Hartsoc...

In this anthology, prominent contemporary theorists assess the benefits and dangers of postmodernism for feminist theory. The contributors examine the meaning of postmodernism both as a methodological position and a diagnosis of the times. They consider such issues as the nature of personal and social identity today, the political implications of recent aesthetic trends, and the consequences of changing work and family relations on women's lives. Contributors: Seyla Benhabib, Susan Bordo, Judith Butler, Christine Di Stefano, Jane Flax, Nancy Fraser, Donna Haraway, Sandra Harding, Nancy Hartsock, Andreas Huyssen, Linda J. Nicholson, Elspeth Probyn, Anna Yeatman, Iris Young.

Dieser Download kann aus rechtlichen Gründen nur mit Rechnungsadresse in A, B, BG, CY, CZ, D, DK, EW, E, FIN, F, GR, HR, H, IRL, I, LT, L, LR, M, NL, PL, P, R, S, SLO, SK ausgeliefert werden.