For Better or for Worse (eBook, ePUB)

Translation as a Tool for Change in the South Pacific

PAYBACK Punkte

11 °P sammeln!

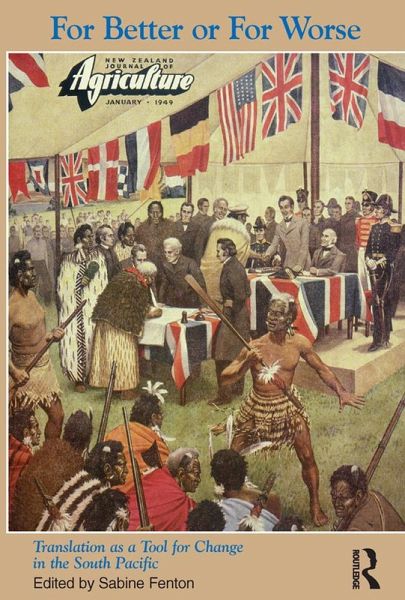

The essays in this book explore the vital role translation has played in defining, changing and redefining linguistic, cultural, ethnic and political identities in several nations of the South Pacific.While in other parts of the world postcolonial scholars have scrutinized the role and history of translation and exposed its close relationship with the colonizers, this has not yet happened in the specific region covered in this collection. In translation studies the Pacific region is terra incognita.The writers of this volume of essays reveal that in the Pacific, as in all other once colonized ...

The essays in this book explore the vital role translation has played in defining, changing and redefining linguistic, cultural, ethnic and political identities in several nations of the South Pacific.

While in other parts of the world postcolonial scholars have scrutinized the role and history of translation and exposed its close relationship with the colonizers, this has not yet happened in the specific region covered in this collection. In translation studies the Pacific region is terra incognita.

The writers of this volume of essays reveal that in the Pacific, as in all other once colonized parts of the world, colonialism and translation went hand in hand. The unsettling power of translation is described as it effected change for better or for worse. While the Pacific Islanders' encounter with the Europeans has previously been described as having a 'Fatal Impact', the authors of these essays are further able to demonstrate that the Pacific Islanders were not only victims but also played an active role in the cross-cultural events they were party to and in shaping their own destinies.

Examples of the role of translation in effecting change - for better or for worse - abound in the history of the nations of the Pacific. These stories are told here in order to bring this region into the mainstream scholarly attention of postcolonial and translation studies.

While in other parts of the world postcolonial scholars have scrutinized the role and history of translation and exposed its close relationship with the colonizers, this has not yet happened in the specific region covered in this collection. In translation studies the Pacific region is terra incognita.

The writers of this volume of essays reveal that in the Pacific, as in all other once colonized parts of the world, colonialism and translation went hand in hand. The unsettling power of translation is described as it effected change for better or for worse. While the Pacific Islanders' encounter with the Europeans has previously been described as having a 'Fatal Impact', the authors of these essays are further able to demonstrate that the Pacific Islanders were not only victims but also played an active role in the cross-cultural events they were party to and in shaping their own destinies.

Examples of the role of translation in effecting change - for better or for worse - abound in the history of the nations of the Pacific. These stories are told here in order to bring this region into the mainstream scholarly attention of postcolonial and translation studies.

Dieser Download kann aus rechtlichen Gründen nur mit Rechnungsadresse in A, B, BG, CY, CZ, D, DK, EW, E, FIN, F, GR, HR, H, IRL, I, LT, L, LR, M, NL, PL, P, R, S, SLO, SK ausgeliefert werden.