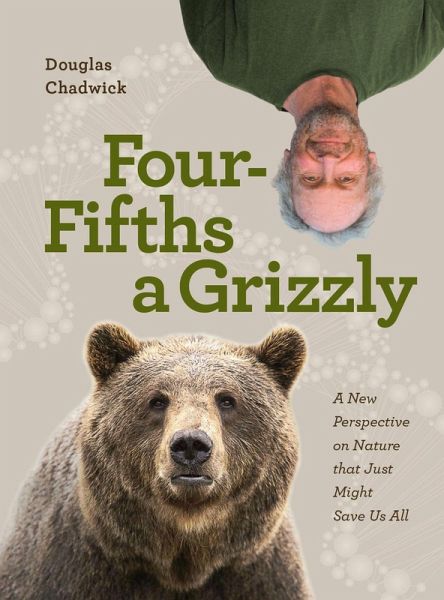

Four Fifths a Grizzly (eBook, ePUB)

A New Perspective on Nature that Just Might Save Us All

Versandkostenfrei!

Sofort per Download lieferbar

8,95 €

inkl. MwSt.

Weitere Ausgaben:

PAYBACK Punkte

4 °P sammeln!

What do you think of when you think of Nature? Prolific author and National Geographic writer Doug Chadwick's fresh look at human's place in the natural world. In his accessible and engaging style, Chadwick approaches the subject from a scientific angle, with the underlying message that from the perspective of DNA humans are not all that different from any other creature. He begins by showing the surprisingly close relationship between human DNA and that of grizzly bears, with whom we share 80 percent of our DNA. We are 60 percent similar to a salmon, 40 percent the same as many insects, and 2...

What do you think of when you think of Nature? Prolific author and National Geographic writer Doug Chadwick's fresh look at human's place in the natural world. In his accessible and engaging style, Chadwick approaches the subject from a scientific angle, with the underlying message that from the perspective of DNA humans are not all that different from any other creature. He begins by showing the surprisingly close relationship between human DNA and that of grizzly bears, with whom we share 80 percent of our DNA. We are 60 percent similar to a salmon, 40 percent the same as many insects, and 24 percent of our genes match those of a wine grape. He reflects on the value of exposure to nature on human biochemistry and mentality, that we are not that far removed from our ancestors who lived closer to nature. He highlights examples of animals using "human" traits, such as tools and play. He ends the book with two examples of the healing benefits of turning closer to nature: island biogeography and the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative. This book is a reflection on man's rightful place in the ecological universe. Using personal stories, recounting how he came to love and depend on the Great Outdoors and how he learned his place in the system of Nature, Chadwick challenges anyone to consider whether they are separate from or part of nature. The answer is obvious, that we are an indivisible from all elements of a system that is greater than ourselves and should never be neglected, taken advantage of, or exploited. This is a fresh and engaging take on man's relationship to nature by a respected and experienced author.

Dieser Download kann aus rechtlichen Gründen nur mit Rechnungsadresse in A, D ausgeliefert werden.