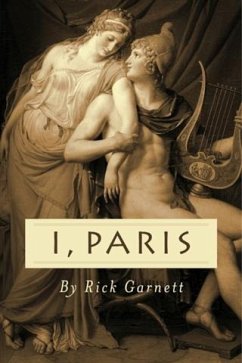

"Paris and Helen-more than a romance, this book depicts the adventures and inner life of the Trojan prince Paris, a complex figure in a world of stark simplicity, moving through passion, betrayal and violence to a stunning finale. Through interpolation of gripping action scenes, tender vignettes, and vivid dialogue, the book gives new depth and richness to the classic story of Paris, Helen of Troy, and the war their stolen love engendered.

The story of Helen and her flight from Sparta with Paris, son of Priam, has been so often and variously told that a reader may justly ask, "Why another iteration?" Here is my attempt at justification for my particular treatment of this fertile theme.

First, though Paris has a role in any story dealing with the Trojan saga, he seems regularly to be overshadowed by Helen herself, the icon of perfect female beauty, and, obviously, a tough act to follow.

Second, I regard Paris as the most enigmatic figure in all of classical literature. Typically, he is portrayed as a weak, almost effeminate, counterpoint to the heroic ideal embodied in the other prominent male figures of the Trojan conflict. But, a careful reading of the Iliad reveals that even Homer had a more nuanced view.

Hector, though predominantly scornful, admits that no one just and fair could underrate Paris as a fighter, and Homer himself compares Paris setting out for battle to a galloping stallion, filled with pride and speed.

Moreover, almost alone among Homeric warriors, Paris is virtually immune to criticism, not, I think, from a genuine "I deserve it" type of humility (though he does use those words in response to Hector's chiding), but more from a sort of above-it-all insouciance.

When Hector scathingly remarks that Paris' lyre and good looks will do him no good in a fight with Menelaus, Paris simply reminds him that the gifts of any immortal, including Aphrodite, should not be spurned. And, when Helen berates Paris for returning safely (with Aphrodite's help) after his defeat by Menelaus, Paris responds, in effect, that "tomorrow is another day," and proposes that they "lose themselves in love."

In short, for many years I have found the Paris of the Iliad a complex figure, inviting a more complete and rounded examination and portrayal than has been the norm to date. In striving for this goal, I adhere, for the most part, to the main features of "the canon" as presented in the Iliad. In addition, many readers will recognize the provenance of the Iphigenia at Aulis segment in Euripides' play by that name, of Hecuba's dream of Troy's destruction in Virgil's Aeneid, and of the nymph Oenone in Ovid's Heroides. These and other ancient sources, delightful in themselves, leave ample room for elaboration into a story with Paris himself as the main character. I have tried to produce such a story by purely imaginary interpolations of new but compatible material. Hopefully, the reader will find the resulting hybrid entertaining, and conducive to a greater appreciation of the magnificent originals.

Finally, a word on style, with apologies to classicists; Greek and Latin epics were written in dactylic hexameter (roughly, dum da da, dum da da, dum dum). This meter is well suited in those languages for expressing a sort of hypnotic solemnity, but is highly artificial for English. My attempt to capture some of the epic tone led me to favor iambics (da dum, da dum), a more natural, but still stylized, English rhythm, a la Shakespeare. The fruits of this effort, if any, will be realized best if the story is read slowly, or even aloud, as the epics were in classical times.

The story of Helen and her flight from Sparta with Paris, son of Priam, has been so often and variously told that a reader may justly ask, "Why another iteration?" Here is my attempt at justification for my particular treatment of this fertile theme.

First, though Paris has a role in any story dealing with the Trojan saga, he seems regularly to be overshadowed by Helen herself, the icon of perfect female beauty, and, obviously, a tough act to follow.

Second, I regard Paris as the most enigmatic figure in all of classical literature. Typically, he is portrayed as a weak, almost effeminate, counterpoint to the heroic ideal embodied in the other prominent male figures of the Trojan conflict. But, a careful reading of the Iliad reveals that even Homer had a more nuanced view.

Hector, though predominantly scornful, admits that no one just and fair could underrate Paris as a fighter, and Homer himself compares Paris setting out for battle to a galloping stallion, filled with pride and speed.

Moreover, almost alone among Homeric warriors, Paris is virtually immune to criticism, not, I think, from a genuine "I deserve it" type of humility (though he does use those words in response to Hector's chiding), but more from a sort of above-it-all insouciance.

When Hector scathingly remarks that Paris' lyre and good looks will do him no good in a fight with Menelaus, Paris simply reminds him that the gifts of any immortal, including Aphrodite, should not be spurned. And, when Helen berates Paris for returning safely (with Aphrodite's help) after his defeat by Menelaus, Paris responds, in effect, that "tomorrow is another day," and proposes that they "lose themselves in love."

In short, for many years I have found the Paris of the Iliad a complex figure, inviting a more complete and rounded examination and portrayal than has been the norm to date. In striving for this goal, I adhere, for the most part, to the main features of "the canon" as presented in the Iliad. In addition, many readers will recognize the provenance of the Iphigenia at Aulis segment in Euripides' play by that name, of Hecuba's dream of Troy's destruction in Virgil's Aeneid, and of the nymph Oenone in Ovid's Heroides. These and other ancient sources, delightful in themselves, leave ample room for elaboration into a story with Paris himself as the main character. I have tried to produce such a story by purely imaginary interpolations of new but compatible material. Hopefully, the reader will find the resulting hybrid entertaining, and conducive to a greater appreciation of the magnificent originals.

Finally, a word on style, with apologies to classicists; Greek and Latin epics were written in dactylic hexameter (roughly, dum da da, dum da da, dum dum). This meter is well suited in those languages for expressing a sort of hypnotic solemnity, but is highly artificial for English. My attempt to capture some of the epic tone led me to favor iambics (da dum, da dum), a more natural, but still stylized, English rhythm, a la Shakespeare. The fruits of this effort, if any, will be realized best if the story is read slowly, or even aloud, as the epics were in classical times.

Dieser Download kann aus rechtlichen Gründen nur mit Rechnungsadresse in A, B, BG, CY, CZ, D, DK, EW, E, FIN, F, GR, HR, H, IRL, I, LT, L, LR, M, NL, PL, P, R, S, SLO, SK ausgeliefert werden.