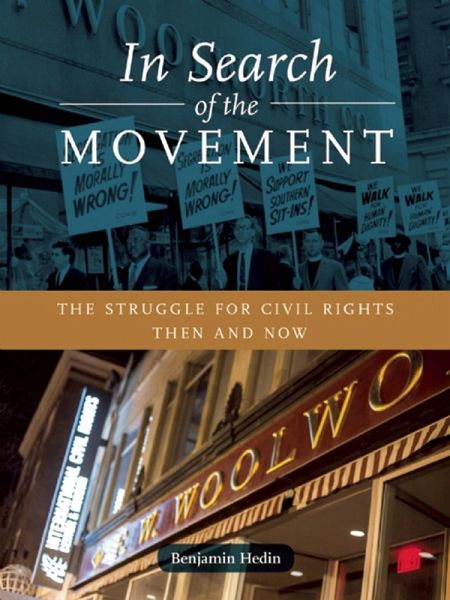

In Search of the Movement (eBook, ePUB)

The Struggle for Civil Rights Then and Now

Versandkostenfrei!

Sofort per Download lieferbar

8,95 €

inkl. MwSt.

Weitere Ausgaben:

PAYBACK Punkte

4 °P sammeln!

"Benjamin Hedin went looking for the civil rights movement's past, but he also ran smack into the present, which can suddenly look like the past and then just as suddenly look totally different. By bringing stirring people like Septima Clark into focus, Hedin does what good historians do, but by entwining history with current events, he does a lot more. Here is a haunting meditation on living in history as well as with it."--Sean Wilentz, author of The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln"In Search of the Movement is a true marvel. Benjamin Hedin's insightful combination of reporta...

"Benjamin Hedin went looking for the civil rights movement's past, but he also ran smack into the present, which can suddenly look like the past and then just as suddenly look totally different. By bringing stirring people like Septima Clark into focus, Hedin does what good historians do, but by entwining history with current events, he does a lot more. Here is a haunting meditation on living in history as well as with it."--Sean Wilentz, author of The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln

"In Search of the Movement is a true marvel. Benjamin Hedin's insightful combination of reportage and history of the Civil Rights movement allows us to see the era with fresh eyes. By tracing the continued legacy of the black freedom struggle from the 1960s to the present, this gem of a book wonderfully illuminates how the movement is living and thriving in our own time."--Peniel Joseph, author of Stokely: A Life and Waiting 'Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America

"Beloved community and the exuberant humanism of the Civil Rights movement have never been so vividly rendered. Carry this book with you as a guide through our own anxious age. Beautifully written, sharply observed, whimsical and tender, In Search of the Movement is a road trip into America's better self."--Charles Marsh, author of God's Long Summer: Stories of Faith and Civil Rights

In March of 1965, Martin Luther King led thousands in an epic march from Selma, Alabama to the state capital in Montgomery, in what is often seen as the culminating moment of the Civil Rights movement. The Voting Rights Act was signed into law that year, and with Jim Crow eradicated, and schools being desegregated, the movement had supposedly come to an end. America would go on to record its story as an historic success.

Recently, however, the New York Times featured an article that described the reversion of Little Rock's schools to all-black or all-white. The next day, the paper printed a story about a small town in Alabama where African Americans were being denied access to the polls. Massive demonstrations in cities across the country protest the killing of black men by police, while we celebrate a series of 50th-anniversary commemorations of the signature events of the Civil Rights movement. In such a time it is important to ask: In the last fifty years, has America progressed on matters of race, or are we stalled--or even moving backward?

With these questions in mind, Benjamin Hedin set out to look for the Civil Rights movement. "I wanted to find the movement in its contemporary guise," he writes, "which also meant answering the critical question of what happened to it after the 1960s." He profiles legendary figures like John Lewis, Robert Moses, and Julian Bond, and also visits with contemporary leaders such as William Barber II and the staff of the Dream Defenders. But just as powerful--and instructional--are the stories of those whose work goes unrecorded, the organizers and teachers who make all the rest possible.

In these pages the movement is portrayed as never before, as a vibrant tradition of activism that remains in our midst. In Search of the Movement is a fascinating meditation on the patterns of history, as well as an indelible look at the meaning and limits of American freedom.

Benjamin Hedin has written for the New Yorker, Slate, the Nation, and the Chicago Tribune. He's the editor of Studio A: The Bob Dylan Reader, and the producer and author of a forthcoming documentary film, The Blues House.

Dieser Download kann aus rechtlichen Gründen nur mit Rechnungsadresse in A, D ausgeliefert werden.