One Hundred Million Hearts (eBook, ePUB)

PAYBACK Punkte

5 °P sammeln!

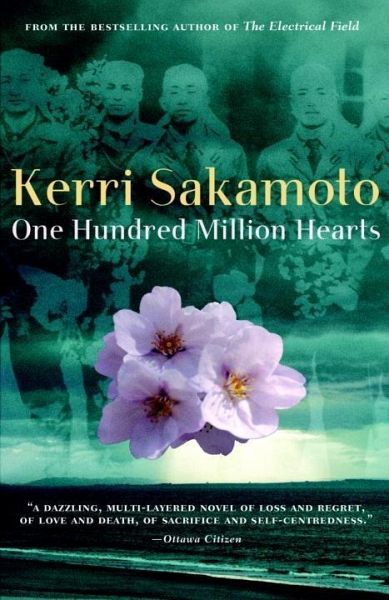

During the Second World War, the Japanese government stirred the people to support its war effort with the image of 'One hundred million hearts beating as one human bullet to defeat the enemy.' Kerri Sakamoto, winner of the Commonwealth Writers' Prize and the Japan-Canada Literary Award for her first novel The Electrical Field, draws on this wartime propaganda in her second novel as she casts light on a fascinating figure from wartime Japan: the kamikaze pilot. These devout young men offered their lives to fly planes into enemy artillery; both human sacrifice and deadly weapon. A cherry blosso...

During the Second World War, the Japanese government stirred the people to support its war effort with the image of 'One hundred million hearts beating as one human bullet to defeat the enemy.' Kerri Sakamoto, winner of the Commonwealth Writers' Prize and the Japan-Canada Literary Award for her first novel The Electrical Field, draws on this wartime propaganda in her second novel as she casts light on a fascinating figure from wartime Japan: the kamikaze pilot. These devout young men offered their lives to fly planes into enemy artillery; both human sacrifice and deadly weapon. A cherry blossom painted on the sides of the bomber symbolized the beauty and ephemerality of nature. Coming back alive from a sacred mission was shameful failure. To succeed meant transformation into an eternal flower reincarnation as the plane exploded like a fiery blossom in the sky. In One Hundred Million Hearts, Miyo is a young Canadian woman who has been cared for all her life by her uncommunicative but devoted Japanese-Canadian father. Her mother died soon after her birth, and a disfigurement prevented the left side of her body from developing the same way as the right, causing her to be reliant on her father's help. One day, commuting to work by subway when he can no longer drive her around, she is accidentally caught in the train doors, and rescued by a man who quickly professes his love for her. The joy of this nurturing and joyful relationship removes her from the almost claustrophobic shelter of home, but as she grows distant from her father, his strength begins to fade; until one day she receives the terrible news of his death. It is only then that she discovers his secret past. The woman he always called his girlfriend was in fact his wife; they had a daughter in Japan, but gave her up for adoption. Now the daughter, Hana, is an artist in Tokyo. Amazed that she has a half-sister, Miyo travels there to meet her. Hana is bitter about being abandoned by her father, and has thrown herself into her work with almost destructive intensity. Through Hana, Miyo learns more of their father's hidden past. Though born in Canada, he was sent to university in Japan; in 1943, Japan was losing the war and the army began conscripting even students. He volunteered as a kamikaze pilot; yet he survived. Hana's obsession with their father's wartime history takes the shape of huge paintings of flowers adorned with the faces of kamikaze pilots and the red threads that one thousand schoolgirls sewed onto the white sash of every pilot that made this suicidal mission. If only he had not hoarded his secrets, thinks Miyo as she struggles to understand modern Japan and her father's past. Why did he not fulfill his ultimate sacrifice, but live to care for her? The reader is drawn into the daily struggles of each of the characters and their rich interior lives through a lyrical portrait of Japanese life that has been compared to David Guterson's Snow Falling on Cedars and Arthur Golden's Memoirs of a Geisha. The Montreal Gazette said Kerri Sakamoto has created in Miyo a marvelously complex, compelling character who is transformed...to a woman who runs and dances and loves, not in innocence, but in full, terrifying knowledge.

Dieser Download kann aus rechtlichen Gründen nur mit Rechnungsadresse in A, B, BG, CZ, D, DK, EW, E, FIN, F, GR, HR, H, I, LT, L, LR, NL, PL, P, R, S, SLO, SK ausgeliefert werden.