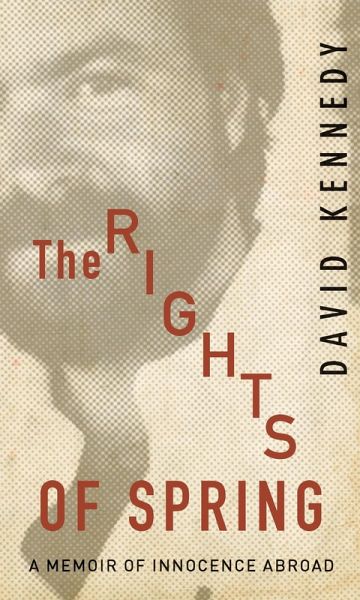

Rights of Spring (eBook, ePUB)

PAYBACK Punkte

9 °P sammeln!

Ana reported being blindfolded, doused in cold water. She was tied to a metal frame; electrodes were fastened to her body. Someone cranked a hand-operated generator. One spring more than twenty years ago, David Kennedy visited Ana in an Uruguayan prison as part of the first wave of humanitarian activists to take the fight for human rights to the very sites where atrocities were committed. Kennedy was eager to learn what human rights workers could do, idealistic about changing the world and helping people like Ana. But he also had doubts. What could activists really change? Was there something ...

Ana reported being blindfolded, doused in cold water. She was tied to a metal frame; electrodes were fastened to her body. Someone cranked a hand-operated generator.

One spring more than twenty years ago, David Kennedy visited Ana in an Uruguayan prison as part of the first wave of humanitarian activists to take the fight for human rights to the very sites where atrocities were committed. Kennedy was eager to learn what human rights workers could do, idealistic about changing the world and helping people like Ana. But he also had doubts. What could activists really change? Was there something unseemly about humanitarians from wealthy countries flitting into dictatorships, presenting themselves as white knights, and taking in the tourist sites before flying home? Kennedy wrote up a memoir of his hopes and doubts on that trip to Uruguay and combines it here with reflections on what has happened to the world of international humanitarianism since.

Now bureaucratized, naming and shaming from a great height in big-city office towers, human rights workers have achieved positions of formidable power. They have done much good. But the moral ambiguity of their work and questions about whether they can sometimes cause real harm endure. Kennedy tackles those questions here with his trademark combination of narrative drive and unflinching honesty. This is a powerful and disturbing tale of the bright sides and the dark sides of the humanitarian world built by good intentions.

One spring more than twenty years ago, David Kennedy visited Ana in an Uruguayan prison as part of the first wave of humanitarian activists to take the fight for human rights to the very sites where atrocities were committed. Kennedy was eager to learn what human rights workers could do, idealistic about changing the world and helping people like Ana. But he also had doubts. What could activists really change? Was there something unseemly about humanitarians from wealthy countries flitting into dictatorships, presenting themselves as white knights, and taking in the tourist sites before flying home? Kennedy wrote up a memoir of his hopes and doubts on that trip to Uruguay and combines it here with reflections on what has happened to the world of international humanitarianism since.

Now bureaucratized, naming and shaming from a great height in big-city office towers, human rights workers have achieved positions of formidable power. They have done much good. But the moral ambiguity of their work and questions about whether they can sometimes cause real harm endure. Kennedy tackles those questions here with his trademark combination of narrative drive and unflinching honesty. This is a powerful and disturbing tale of the bright sides and the dark sides of the humanitarian world built by good intentions.