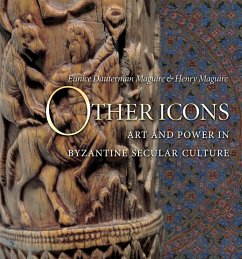

Romanesque Art and Icons + Other Iconographic Studies (eBook, ePUB)

PAYBACK Punkte

0 °P sammeln!

This book is a collection of studies on the general theme of Orthodox icons. 1) As the title of the book indicates, the first article deals with the similarity between religious images of the Romanesque period (900-1200) in Western Europe and Orthodox icons. As the difference between icons and later Western religious images-Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque etc.-is felt first on the intuitive and then explained on the rational level, so icons and Romanesque religious images manifest a similarity first felt on a non-rational level, but never before explained in thought. The first in the series of si...

This book is a collection of studies on the general theme of Orthodox icons. 1) As the title of the book indicates, the first article deals with the similarity between religious images of the Romanesque period (900-1200) in Western Europe and Orthodox icons. As the difference between icons and later Western religious images-Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque etc.-is felt first on the intuitive and then explained on the rational level, so icons and Romanesque religious images manifest a similarity first felt on a non-rational level, but never before explained in thought. The first in the series of six studies attempts to explain the intuition by positing an ecumenical art, especially for the image of Christ, that would have been comprehensible to everyone in the Christian sphere at the time. It is one thing to make such an affirmation, it is another to demonstrate it convincingly. It is the purpose of this first essay to do both. 2) For a lot of people, science and religion are two opposing spheres or, at best, the one having nothing to do with the other. The confrontations between them during the last two or more centuries are well known. In the realm of Biblical studies, textual criticism and archeological discoveries seem, for many, to undermine the credibility of the Bible. This second article offers the Orthodox icon as a possible tool helping to reconcile two things that for many seem to be irreconcilable. The definition of an icon as an image of a historical person or event shown through the lens of a theological interpretation might be able to open a door leading away from the impasse between the Bible as myth or literal truth. What if certain Biblical stories are verbal images of historical persons and events-their historicity varying according to the story-seen through a particular historico-theological lens? They are then neither myths nor literal histories but rather icons. 3) The third study is a translation of Fr. George Florovsky's article about the image of Sophia (Wisdom) in Christian history, especially in the Byzantine and Russian spheres. He traces the development of such images along two separate lines: Sophia as an Old Testament name for Christ the Logos shown as the Angel of Great Council, such as in the name of the Church of Haghia Sophia in Constantinople (Istanbul), and the allegorical personification of wisdom from the Old Testament and Greek philosophy as the source of human inspiration, generally shown as a woman. In the Russian context, Sophia and its image eventually come to stand for the Virgin Mary. 4) In the Ecumenical Movement, what role do icons play, if any? Do they bring Christians closer together or push them farther apart? What are the attitudes of contemporary Christians toward images as compared to the arguments in favor of images put forward by iconodules during the Iconoclastic Controversy of the 8th and 9th centuries? In the second part of this study, "the jury is still out," meaning that it cannot be stated with certainly whether icons will ultimately lead to more unity or more discord. There are presently signs of both movements. 5) Can and should icons be blessed? Does a religious painting become an icon when a priest blesses it? What makes an icon an icon? The author attempts to show that not only the notion of blessing icons but also the practice of doing so are very late arrivals in the Orthodox world and have their source and inspiration elsewhere than in the patristic tradition that is the foundation of the Orthodox theological world view. 6) And finally, the last study is an autobiographical version of the author's interest in the Ecumenical Movement.

Dieser Download kann aus rechtlichen Gründen nur mit Rechnungsadresse in A, B, CY, CZ, D, DK, EW, E, FIN, F, GR, H, IRL, I, LT, L, LR, M, NL, PL, P, R, S, SLO, SK ausgeliefert werden.