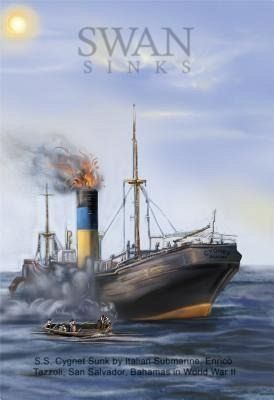

Swan Sinks (eBook, ePUB)

SS Cygnet Sunk by Italian Submarine Enrico Tazzoli, San Salvador, Bahamas in World War II

PAYBACK Punkte

1 °P sammeln!

The human element of a relatively small incident like the loss of the relatively small, 3530-ton Cygnet, is both compelling and illustrative of the larger, global struggle. The ship itself had served the US government in World War I, and run between Europe and South America for decades. Built Dutch, she was owned and crewed mostly Greek, flagged to Panama, and trading for Canadians to and from South America and the Caribbean. Though the owners had a contract (charter party) stating no deck cargo was to be carried, a young Bahamian boy and his family retrieved bales of rubber which floated free...

The human element of a relatively small incident like the loss of the relatively small, 3530-ton Cygnet, is both compelling and illustrative of the larger, global struggle. The ship itself had served the US government in World War I, and run between Europe and South America for decades. Built Dutch, she was owned and crewed mostly Greek, flagged to Panama, and trading for Canadians to and from South America and the Caribbean. Though the owners had a contract (charter party) stating no deck cargo was to be carried, a young Bahamian boy and his family retrieved bales of rubber which floated free after the sinking. The Cygnet men were the only Allied sailors rescued by the Monarch of Nassau, though on another Bahamian vessel, the Ena K., they shared space with survivors of other shipwrecks, and missed sailing with Sydney Poitier by mere weeks.

The attack itself was recorded for posterity live by the Italians, so that we can watch it online - even whilst on the move ourselves. The crew, mostly from small islands in the Greek archipelago (only two out of 28 Greeks were from Athens, and most were from Andros or Chios), were also from Romania and Spain. They were able to interact with their Italian attackers for roughly an hour, then encounter a one-legged white man in a rowboat who guided them between the reefs at 4 am, then accept a ride from Captain Roland Roberts aboard his British-built freighter, before meeting the Duke and Duchess of Windsor in the colony's capital, Nassau. Overall the men would travel by lifeboat, lorry, passenger ship, a motor sailor and train over two weeks before they reached a base, albeit in exile.

In Nassau the sailors were given an open-armed welcome from fellow Greeks from Kalymnos, living industriously in the Bahamas since the late 1800s when they had arrived for the prosperous sponge fishing trade, which had recently collapsed. They shared the island - and no doubt the pubs - with over 100 other cast-up sailors from other vessels. From there Captain Charles A. Pettee, master of a wooden freighter built in Harbour Island that was overcrowded with castaways and farmers, were cleared outwards by two American consuls from Minnesota, and interviewed by US Navy intelligence officers before being reunited with their employers in New York. They too had been forced by the war to move from Andros to Athens, London, then to New York. For most of the sailors, it would take years, until war's end, before they were able to reunite with friends and family in Greece. Some of them would opt to stay in America, because of the Cygnet.

The loss of the Cygnet gave the men on both sides of the steel vessels involved plenty to photograph and film, talk and write about, and remember. There is a certain irony in the Cygnet skipper's letter of protest, filed in Nassau, when men on both sides admit that interactions between Italians and Greek were jocular and relaxed. Interestingly, it was the Greek, and not the Italian sailors, who lived to tell the tale. Within a year the Tazzoli, too, was at the sea floor, her commander dead by his own hand, his legacy only resurrected, with an Italian submarine named after him, long after the war.

The attack itself was recorded for posterity live by the Italians, so that we can watch it online - even whilst on the move ourselves. The crew, mostly from small islands in the Greek archipelago (only two out of 28 Greeks were from Athens, and most were from Andros or Chios), were also from Romania and Spain. They were able to interact with their Italian attackers for roughly an hour, then encounter a one-legged white man in a rowboat who guided them between the reefs at 4 am, then accept a ride from Captain Roland Roberts aboard his British-built freighter, before meeting the Duke and Duchess of Windsor in the colony's capital, Nassau. Overall the men would travel by lifeboat, lorry, passenger ship, a motor sailor and train over two weeks before they reached a base, albeit in exile.

In Nassau the sailors were given an open-armed welcome from fellow Greeks from Kalymnos, living industriously in the Bahamas since the late 1800s when they had arrived for the prosperous sponge fishing trade, which had recently collapsed. They shared the island - and no doubt the pubs - with over 100 other cast-up sailors from other vessels. From there Captain Charles A. Pettee, master of a wooden freighter built in Harbour Island that was overcrowded with castaways and farmers, were cleared outwards by two American consuls from Minnesota, and interviewed by US Navy intelligence officers before being reunited with their employers in New York. They too had been forced by the war to move from Andros to Athens, London, then to New York. For most of the sailors, it would take years, until war's end, before they were able to reunite with friends and family in Greece. Some of them would opt to stay in America, because of the Cygnet.

The loss of the Cygnet gave the men on both sides of the steel vessels involved plenty to photograph and film, talk and write about, and remember. There is a certain irony in the Cygnet skipper's letter of protest, filed in Nassau, when men on both sides admit that interactions between Italians and Greek were jocular and relaxed. Interestingly, it was the Greek, and not the Italian sailors, who lived to tell the tale. Within a year the Tazzoli, too, was at the sea floor, her commander dead by his own hand, his legacy only resurrected, with an Italian submarine named after him, long after the war.

Dieser Download kann aus rechtlichen Gründen nur mit Rechnungsadresse in A, D ausgeliefert werden.