Thoughts on Art and Life (eBook, ePUB)

"Behind the Genius"

Redaktion: Einstein, Lewis / Illustrator: Ukray, Murat / Übersetzer: Baring, Maurice

PAYBACK Punkte

0 °P sammeln!

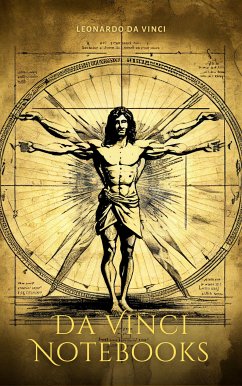

Leonardo's views of aesthetic are all important in his philosophy of life and art. The worker's thoughts on his craft are always of interest. They are doubly so when there is in them no trace of literary self-consciousness to blemish their expression. He recorded these thoughts at the instant of their birth, for a constant habit of observation and analysis had early developed with him into a second nature. His ideas were penned in the same fragmentary way as they presented themselves to his mind, perhaps with no intention of publishing them to the world. But his ideal of art depended intimatel...

Leonardo's views of aesthetic are all important in his philosophy of life and art. The worker's thoughts on his craft are always of interest. They are doubly so when there is in them no trace of literary self-consciousness to blemish their expression. He recorded these thoughts at the instant of their birth, for a constant habit of observation and analysis had early developed with him into a second nature. His ideas were penned in the same fragmentary way as they presented themselves to his mind, perhaps with no intention of publishing them to the world. But his ideal of art depended intimately, none the less, on the system he had thrown out seemingly in so haphazard a manner.The long obscurity of the Dark Ages lifted over Italy, awakening to a national though a divided consciousness. Already two distinct tendencies were apparent. The practical and rational, on the one hand, was soon to be outwardly reflected in the burgher-life of Florence and the Lombard cities, while at Rome it had even then created the civil organization of the curia. The novella was its literary triumph. In art it expressed itself simply, directly and with vigour. Opposed to this was the other great undercurrent in Italian life, mystical, religious and speculative, which had run through the nation from the earliest times, and received fresh volume from mediaeval Christianity, encouraging ecstatic mysticism to drive to frenzy the population of its mountain cities. Umbrian painting is inspired by it, and the glowing words of Jacopone da Todi expressed in poetry the same religious fervour which the life of Florence and Perugia bore witness to in action.Italy developed out of the relation and conflict of these two forces the rational with the mystical. Their later union in the greater men was to form the art temperament of the Renaissance. The practical side gave it the firm foundation of rationalism and reality on which it rested; the mystical guided its endeavour to picture the unreal in terms of ideal beauty.The first offspring of this union was Leonardo. Since the decay of ancient art no painter had been able to fully express the human form, for imperfect mastery of technique still proved the barrier. Leonardo was the first completely to disengage his personality from its constraint, and make line express thought as none before him could do. Nor was this his only triumph, but rather the foundation on which further achievement rested. Remarkable as a thinker alone, he preferred to enlist thought in the service of art, and make art the handmaid of beauty. Leonardo saw the world not as it is, but as he himself was. He viewed it through the atmosphere of beauty which filled his mind, and tinged its shadows with the mystery of his nature.From his earliest years, the elements of greatness were present in Leonardo. But the maturity of his genius came unaffected from without. He barely noticed the great forces of the age which in life he encountered. After the first promise of his boyhood in the Tuscan hills, his youth at Florence had been spent under Verrocchio as a master, in company with those whose names were later to brighten the pages of Italian art. At one time he contemplated entering the service of an Oriental prince. Instead, he entered that of Caesar Borgia, as military engineer, and the greatest painter of the age became inspector of a despot's strongholds. But his restless nature did not leave him long at this. Returning to Florence he competed with Michelangelo; yet the service of even his native city could not retain him. His fame had attracted the attention of a new patron of the arts, prince of the state which had conquered his first master. In this his last venture, he forsook Italy, only to die three years later at Amboise, in the castle of the French king.

Dieser Download kann aus rechtlichen Gründen nur mit Rechnungsadresse in A, B, BG, CY, CZ, D, DK, EW, E, FIN, F, GR, H, IRL, I, LT, L, LR, M, NL, PL, P, R, S, SLO, SK ausgeliefert werden.