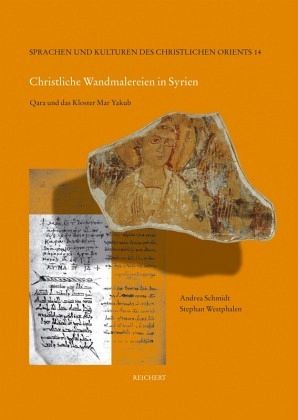

Christliche Wandmalerei in Syrien

Qara und das Kloster Mar Yakub

Hrsg. im Auftr.. d. Dtsch. Archäolog. Institut v. Andrea B. Schmidt u. Stephan Westphalen

Versandkostenfrei!

Versandfertig in 2-4 Wochen

89,00 €

inkl. MwSt.

PAYBACK Punkte

0 °P sammeln!

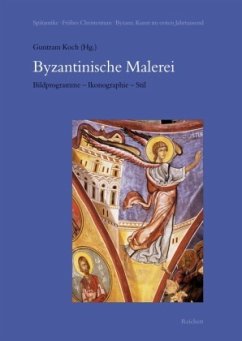

Die in den letzten Jahren intensivierte Erforschung der mittelalterlichen Malerei im Christlichen Orient wird durch den angekündigten Band um eine beachtliche Reihe von Wandbildern bereichert, die erst jüngst im Rahmen von Restaurierungsarbeiten und Ausgrabungen zu Tage kamen. Der Schwerpunkt liegt mit dem Jakobskloster bei Qara und der Eliasgrotte von Macarrat Saydanaya auf dem Qalamungebirge nördlich von Damaskus, der Horizont ist mit dem Kastron von Androna aber bis in das syrische Steppengebiet östlich von Hama gesteckt. Neben einer ausführlichen Dokumentation behandeln die kunsthistorischen Beiträge auch den künstlerischen Austausch Syriens mit Zypern und die Ausbildung eines syrischen Regionalstils um das Jahr 1200. Vorangestellt ist ein historischer Abriß der Ortschaft Qara, die bis 1266 rein melkitisch war. Weitere Beiträge sind der Restaurierung und der chemischen Probenanlayse der Wandmalereien sowie der syrischen und griechischen Epigraphik gewidmet.

Die Beiträge des Sammelbands sind der Veröffentlichung von Wandmalereien gewidmet, die ausnahmslos erst in den letzten Jahren im Rahmen von Restaurierungsarbeiten und Ausgrabungen zutage kamen. Der Schwerpunkt liegt mit dem Jakobskloster bei Qara und der Eliasgrotte von Ma'arrat Saydnaya zwar auf dem Qalamungebirge nördlich von Damaskus, der Horizont ist mit Andarin aber weiter bis in das syrische Steppengebiet östlich von Hama gesteckt. Chronologisch sind vor allem die Jahrzehnte um das Jahr 1200 vertreten. In Qara ist zusätzlich eine ältere Fassung des frühen elften Jahrhunderts erhalten, und das Wandbild in Andarin führt in die Zeit des siebten und achten Jahrhunderts. Im Vordergrund stehen gattungsspezifische Fragen nach der thematischen Auswahl der Wandbilder, ihrer programmatischen Verteilung im Raum und ihren formalen Kriterien. Gleichermaßen wird das kunsthistorische Umfeld berücksichtigt, das mit dem syrisch-orthodoxen Moseskloster bei Nebek (Dair Mar Musa) und den ausgemalten Kapellen im Hinterland von Tripolis ebenfalls erst in den letzten Jahren erschlossen wurde.

Thematisch ist die syrische Wandmalerei durch die Auswahl ikonenhafter Heiligenbilder charakterisiert, die ohne erkennbares Programm an den Wänden aufgereiht sind. Ein narrativer Christuszyklus wie in Qara oder ein liturgisches Thema wie die Bischofsprozession in der Eliasgrotte sind im Rahmen eines einheitlichen Ausmalungsprogramms eher die Ausnahme. In formaler Hinsicht werden die Wandbilder von zwei Tendenzen geprägt: Die eine vertritt eine byzantinisierende Richtung, die von Zypern beeinflusst ist und möglicherweise über Antiochia vermittelt wurde. Die zweite kommt vor allem in der Zeit um 1200 zum Tragen und ist als landschaftstypischer Regionalstil sowohl in den syrischen Ausmalungen von Qara und dem Moseskloster bei Nebek als auch gehäuft auf libanesischer Seite vertreten.

Die unterschiedlichen Tendenzen in der Malerei sind aber weder an eine Konfession, noch an ein Territorium gebunden. Dieses Ergebnis ist in mancherlei Hinsicht bemerkenswert. Sowohl die Kirchenspaltungen als Folge des Konzils von Chalcedon (451 n. Chr.) als auch Territorialgrenzen, die sich zwischen den muslimischen, lateinischen und byzantinischen Herrschaftsbereichen verschieben, prägen die Situation der christlichen Minderheiten im westlichen Syrien. Die Wandmalerei scheint davon unbeeinflusst zu sein; sie spiegelt vielmehr einen grenz- und konfessionsübergreifenden Austausch wider, hinter dem ein monastisches Netzwerk zu vermuten ist.

Aus dem Inhalt:

Andrea Schmidt: Zur Geschichte des Bistums Qara im Qalamun

Stephan Westphalen: Das Kloster Mar Yakub und seine Wandmalereien

Mat Immerzeel: The Decoration of the Chapel of the Prophet Elijah in Ma'arrat Saydnaya

Christine Strube: Eine Verkündigungsszene im Kastron von Androna/al-Andarin

Sebastian Brock: The Syriac Inscription of Androna/al-Andarin.

Thematisch ist die syrische Wandmalerei durch die Auswahl ikonenhafter Heiligenbilder charakterisiert, die ohne erkennbares Programm an den Wänden aufgereiht sind. Ein narrativer Christuszyklus wie in Qara oder ein liturgisches Thema wie die Bischofsprozession in der Eliasgrotte sind im Rahmen eines einheitlichen Ausmalungsprogramms eher die Ausnahme. In formaler Hinsicht werden die Wandbilder von zwei Tendenzen geprägt: Die eine vertritt eine byzantinisierende Richtung, die von Zypern beeinflusst ist und möglicherweise über Antiochia vermittelt wurde. Die zweite kommt vor allem in der Zeit um 1200 zum Tragen und ist als landschaftstypischer Regionalstil sowohl in den syrischen Ausmalungen von Qara und dem Moseskloster bei Nebek als auch gehäuft auf libanesischer Seite vertreten.

Die unterschiedlichen Tendenzen in der Malerei sind aber weder an eine Konfession, noch an ein Territorium gebunden. Dieses Ergebnis ist in mancherlei Hinsicht bemerkenswert. Sowohl die Kirchenspaltungen als Folge des Konzils von Chalcedon (451 n. Chr.) als auch Territorialgrenzen, die sich zwischen den muslimischen, lateinischen und byzantinischen Herrschaftsbereichen verschieben, prägen die Situation der christlichen Minderheiten im westlichen Syrien. Die Wandmalerei scheint davon unbeeinflusst zu sein; sie spiegelt vielmehr einen grenz- und konfessionsübergreifenden Austausch wider, hinter dem ein monastisches Netzwerk zu vermuten ist.

Aus dem Inhalt:

Andrea Schmidt: Zur Geschichte des Bistums Qara im Qalamun

Stephan Westphalen: Das Kloster Mar Yakub und seine Wandmalereien

Mat Immerzeel: The Decoration of the Chapel of the Prophet Elijah in Ma'arrat Saydnaya

Christine Strube: Eine Verkündigungsszene im Kastron von Androna/al-Andarin

Sebastian Brock: The Syriac Inscription of Androna/al-Andarin.

Dieser Artikel kann nur an eine deutsche Lieferadresse ausgeliefert werden.